Sunday's postcard, and a progress report on the investigation into the West Plains' toxic water fiasco

December 10, 2023

Ice kicking Trumpeter Swan at the Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge near Cheney

If you’ve wondered why The Daily Rhubarb arrives less frequently this fall it is due, in largest part, to the effort required to get a reportorial handle on a rapidly-moving and bizarre saga. It’s a story that doesn’t even have a good name yet.

It’s not Watergate, nor Love Canal. It’s the West Plains water contamination story—a disturbing and as-yet unfolding drama laced in acronyms and secrecy, and exhaling more than a whiff of scandal. I’m including an inventory of the pieces I’ve written thus far at the end of this dispatch. But I thought it would be helpful, now six months in, to register an update and progress report. Again, I’m offering this reporting for free as a public service, but please feel encouraged to become a paid subscriber to The Daily Rhubarb if you’re not already. Investigative reporting is expensive and I do need and deeply appreciate your support.

Delta Airlines Boeing 737 on final approach over the Palisades neighborhood to a landing at Spokane International Airport

A TALE OF TWO AIRPORTS

Through one lens into the story, this is a tale of two airports—Fairchild Air Force Base and Spokane International Airport (SIA), located just four miles apart in the westward opening “V” between U.S. Highway 2 and Interstate-90. For decades both airports used large amounts of Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) a suppressant specifically developed in the 1970s to fight aviation fires.

The problem is the AFFF recipe was loaded with PFAS (Per- and Polyfluoralkyl Substances) a class of synthetic molecules composed of long, tightly-bonded chains of carbon and fluorine atoms. The chemicals are water soluble, fiendish in the range of their toxic effects, and extremely resilient. Although the PFAS-laden foam is rapidly being phased out to comply with a recent federal mandate—it persists in the environment. Due to its stability and solubility, it is pervasive in West Plains groundwater north of I-90 and extending well to the north of Highway 2, toward the Spokane River.

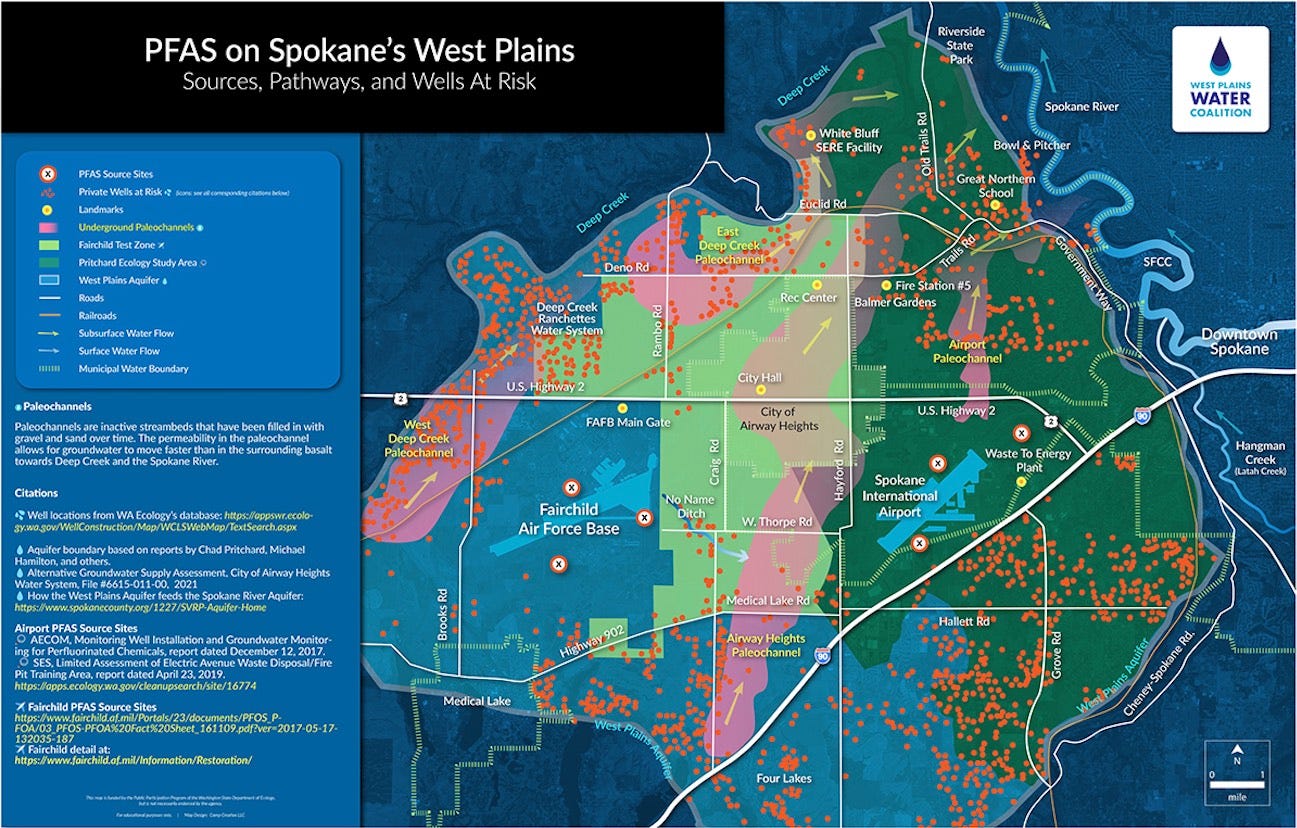

West Plains Water Coalition map of the West Plains aquifer system showing groundwater features and the locations of private wells (displayed as red dots) vulnerable to PFAS contamination.

Though PFAS contamination is common to both FAFB and SIA, there are striking differences between how the Air Force has faced the problem and how SIA has opted—thus far—for denial and obfuscation.

While the Air Force can be criticized for being late to test its groundwater for PFAS, it was proactive in taking responsibility for the contamination. In doing so, the Air Force acknowledged that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had issued a public health advisory on PFAS in 2016. Among other steps, Fairchild began supplying clean water at federal expense to those whose private wells tested positive for PFAS in areas where the contamination is presumed to have come from the base.

In contrast, a SIA spokesperson Todd Woodard told the Seattle Times that the airport wasn’t required to report the detection of PFAS in its groundwater in 2017 or 2019 because the state "had not [yet] formulated mandatory reporting requirements for PFAS.” What he left out is that when the state’s action levels for PFAS became official on January 1, 2022, SIA still didn’t report the evidence of the PFAS contamination—even though some detections were at levels more than a hundred times the state’s action levels.

Fairchild disclosed the existence of PFAS in its groundwater monitoring to a public health official in the spring 2017. But it is both clear and undisputed that when top SIA officials learned of the presence of PFAS contamination in the commercial airport’s groundwater later that year, they chose silence. They made no effort to notify public health entities and nearby residents who get their drinking water from private wells. The contamination only came to light when well-monitoring results and an internal memo were made available earlier this year in response to a public records request. The records request came from from a concerned citizen—one whose well water in the nearby Palisades neighborhood had been contaminated with PFAS.

When notified by the Department of Ecology that it had been designated a “potentially liable person” under the state’s hazardous waste law, SIA contracted with a Washington D.C.-based law firm to push back against the state regulators. In a heated, disheveled letter the E&W Law lawyer first blamed the federal government for not warning the airport about the dangers of the PFAS-laden foam and then went on to criticize Ecology for jumping to the conclusion “that it was the Airport’s PFAS, despite the nearby location of Fairchild AFB, the military use of PFAS at or near the Airport, other known or suspected sources of PFAS immediately adjacent to the Airport, etc.” The letter also chastised Ecology for making “reckless statements” and engaging in “pure speculation without any facts”—thus jeopardizing SIA’s efforts to sell airport property for development.

For its part, Ecology was unfazed. It has since removed the word “potentially” and formally designated SIA as a “responsible person”—meaning SIA is likely on the hook for funding the costs of investigating and remediating the PFAS contamination at SIA.

Some useful background:

•Fairchild had already been designated as a federal Superfund cleanup site when PFAS was detected in its groundwater six years ago. The Air Force base is a federal facility, so its environmental restoration activities are regulated and overseen by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Local stakeholders, including a Spokane Regional Health District representative, are part of a Restoration Advisory Board that the Air Force regularly briefs and consults.

•Spokane International Airport is a joint creation of the City of Spokane and Spokane County. Its managers are hired and are accountable to a jointly appointed board.

•The regulatory framework at SIA is markedly different. As a state facility, the airport is subject to oversight by the Washington State Department of Ecology. But SIA’s wastewater profile in 2017 was limited to a stormwater permit. There were no active hazardous waste permits at SIA at the time the PFAS was discovered and Ecology’s presence was minimal compared to what it is now as it prepares to further investigate PFAS contamination at the airport and devise a cleanup plan under Washington’s Model Toxics Control Act (MTCA).

Hayford Road at the Northern Quest Casino in Airway Heights. The road is a crucial boundary in the plight of private well owners whose water tests positive for PFAS contamination.

A LINE ON THE ASPHALT

When I began following the West Plains PFAS story this past spring, one of the mysteries was a line on the map at Hayford Road, the main north-south arterial on the West Plains. Whether you’re coming from Airway Heights or Spokane, Hayford Road is how you get to the sprawling Northern Quest Casino (itself a litigant in the PFAS contamination).

Hayford Road is also a dividing line of keen interest to private well owners on the West Plains. Simply put, if you find your well is contaminated with PFAS (above the EPA health advisory standard of 70 parts per trillion) you have a good chance of getting help from the Air Force if you live west of Hayford Road. By “help” I mean bottles or jugs of purified water, or a government-funded filtration shack where granular activated carbon is used to remove the PFAS. To be sure, there are maintenance issues with the filtration shacks and other complaints. But at least it’s a tangible offer of assistance that can greatly reduce the cost to a West Plains homeowner in regaining access to clean water.

However, if you live east of Hayford Road and find your well is contaminated you will learn you’re not eligible for federal assistance. The question of why Hayford Road became the line of eligibility was answered by the Air Force just a few weeks ago, when it provided in written answers to questions asked at a public “Listening Session” hosted by the Washington Department of Health in April.

“Hayford Road was designated as the FAFB sampling area’s eastern boundary because Hayford Road is the approximate location of the groundwater divide between the Airway Heights Paleochannel and Airport Paleochannel. Secondly, there [are] other potential contributors to consider in the Airport Paleochannel which need further investigation. The Department of Defense can only take remedial actions for the PFAS associated with DOD use.”

The Air Force’s response is fascinating on a couple levels. The first is that it underscores how important hydrogeology is on the West Plains. The “paleochannels” were literally drilled into basalt bedrock of the West Plains by the Ice Age floods that overwhelmed the Spokane River gorge just to the north. They’re hundreds of feet deep in places and because they were largely filled-in by flood cobbles—they are preferential and highly transmissive pathways for groundwater and, by extension, contaminated groundwater. What the Air Force is saying, in essence, is that it believes the Airway Heights paleochannel is an effective barrier preventing its PFAS contamination from migrating east of Hayford Road.

But the Air Force is also saying something more—that it has reasons to believe the PFAS found in wells east of Hayford Road is coming from Spokane International Airport. This became clear in a recent email the Air Force sent to a West Plains resident who lives east of Hayford and who’d approached the base requesting assistance. While encouraging the home owner to contact the Spokane Regional Health District, the Fairchild official wrote: “The data we have collected so far indicates that PFAS contamination from Fairchild sources does not go east of Hayford Rd. We also know that a second paleochannel controls flow direction from the Spokane Airport and heads north into the area where you currently reside. The Spokane Airport also is a user of AFFF and has trained with it for decades and there are at least two known source areas that have likely impacted groundwater with PFAS constituents that could be in drinking water north of the Airport.

THE BUMPY ROAD AHEAD

At this point it’s hard to predict how the collisions of science, law and politics will sort out because it would appear those collisions will only escalate. Part of the significance of the Hayford Road boundary (determining who gets federal assistance and who may not) is that it’s a signal the Air Force is not going to take a PFAS bullet and a financial hit for the Spokane Airport. That has potential ramifications in part because federal public health resources through ATSDR—the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry—are linked to the federal Superfund program. (ATSDR was actually created as part of the 1980 law creating the Superfund program.)

In short, Fairchild is a Superfund site. SIA is not. As I’ll explain in future reporting this is not a hypothetical complication. It is happening in real time as more West Plains residents learn and are forced to come to grips with the fact that their well water is contaminated, or might become contaminated in the future, because of the solubility and long-lived nature of the PFAS chemicals. Some will learn that the government help they need (and arguably deserve) is unavailable simply because they live on the wrong side of Hayford Road. They will not be happy to learn this.

Another clear complication is the caffeinated brew of local politics and economic development strategies. Commercial development on the West Plains—much of it promoted and brokered by SIA—is currently all the rage. You can see that in the hostile tone and content of SIA’s hired-gun response to Ecology’s notice that the airport had been designated as a “potentially liable person” under the state’s hazardous waste law. Did the emphasis on West Plains development delay and muddle the public health response? The answer appears to be yes, and not just because SIA chose not to report its PFAS groundwater contamination.

PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT

One silver-lining in this troubling and developing story is the creation and work of a new citizen organization—the West Plains Water Coalition—that arose with help from the Friends of Palisades, a volunteer organization rooted in the rural neighborhood just north of the airport, and east of Hayford Road. WPWC was a catalyst for the April “listening session” that brought together representatives from local and state health agencies to hear and respond to residents affected by the PFAS groundwater contamination. WPWC now convenes regular and well-attended gatherings at The Hub meeting hall in Airway Heights, where people affected by the PFAS pollution problem can hear and interact with legal, medical and environmental experts.

This Thursday, December 14th at 7 p.m., WPWC is hosting representatives from the Washington Department of Ecology—Jeremy Schmidt, the project manager for the SIA investigation and remediation, and communication specialist Erika Beresovoy. Chad Pritchard—the geologist who is leading an Ecology-funded “fate and transport” study to better define the sources and groundwater pathways of the PFAS contaminants—will also be present to discuss the status of the study. Pritchard is the chair of Eastern Washington University’s Geology department and, among other publications, has authored and co-authored several technical papers looking at hydrogeology on the West Plains.

—tjc

A POSTSCRIPT, ON PFAS TOXICITY AND HEALTH EFFECTS

Last Thursday evening, at a HUB meeting convened by WPWC, an audience of 90 people heard from two public health experts—Dr. Catherine Karr of the University of Washington’s Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit, and Dr. Frank Velasquez, the Health Officer for the Spokane Regional Health District. Both gave well-prepared Powerpoint presentations on the history of PFAS, its emergence as a serious occupational and public health problem, and medical and epidemiological information on the effects and potential effects of PFAS exposure.

I am not a doctor. But I am a science writer. In an earlier version of my career I wrote a book, Burdens of Proof: Science and Public Accountability in the Field of Environmental Epidemiology, to help guide communities facing situations just like the one confronting the West Plains now. What I thought was missing from both presentations was a better explanation for why the Washington’s State Action Levels (SALs) for PFAS and the EPA’s proposed drinking water standard for PFAS are set not in the parts per million, or parts per billion, but in parts per trillion—orders of magnitude more restrictive than the standards for such well-known toxins as lead, arsenic, and even highly toxic polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

To me it begged an obvious and important question as to why ingestion standards were being set so low, in the parts per trillion. But it didn’t get answered.

Both doctors reported on recent findings of a National Academy of Sciences panel underscoring evidence that PFAS increases risks of impaired anti-body response, elevated cholesterol and pregnancy induced hypertension. Unfortunately, neither touched on the evidence from animal and human studies highlighting increased risks for cancers to the thyroid, pancreas, kidney and testicles. The evidence for cancer risks overlaps with the findings that PFAS chemicals are so-called “endocrine disrupters” that can impair the body’s secretion of hormones leading to a variety of health effects, including cancer.

—tjc

PREVIOUS ARTICLES IN THIS SERIES

•What a Seattle Times investigation reveals about the poisoned groundwater west of Spokane (10/31/23)

•The Spokane Airport’s word bomb response to disclosure of its PFAS contamination problem (10/13/23)

•The state’s wake-up call for Spokane International Airport’s water pollution problem (8/23/23)

•The trouble Spokane's airport may face for not disclosing its contaminated groundwater problem (8/15/23)

•Rough Landing (7/09/23)

•Robert Bilott, and “Exposure,” the story of a historic civil suit against DuPont for PFAS contamination. (06/27/23)

•A primer on the notorious, synthetic chemical that contaminates drinking water from coast to coast. (06/22/23)

•Scoping the “forever chemical” story on the West Plains (6/04/23) .

Thanks for this, Tim. Well researched and reasoned as always.

Bravo Mr. Connor. You've untangled and summarized a complicated spaghetti monster story.