Tuesday's postcard, and a postscript to Sunday's primer on the alarming "forever chemicals" threatening the nation's drinking water

June 27, 2023

Wenatchee River just west of Leavenworth, WA

Sometimes a turning point in a person’s life can mark a turning point for a community, or a nation. The irony of the turning point in Robert Bilott’s life is that it arose from a misunderstanding.

Bilott’s 81 year-old grandmother knew he was a lawyer, but didn’t quite grasp that he was a corporate defense lawyer. So when a neighbor-farmer in Parkersburg, West Virginia was convinced his cows were being poisoned, and needed a lawyer, she gave him the number for Bilott’s private line at the law firm he worked for in Cincinnati.

As he recounts in his 2017 book, Exposure, Bilott almost hung up on the farmer from Parkersburg. The farmer’s name was Earl Tennant. His cows were dying; he had photos and records to prove it, and was adamant in his suspicion that a corporate giant, DuPont, was responsible for contaminating the creek from which the cows were drinking. This was in the fall of 1998. The grisly evidence Tennant collected was impossible for Bilott to dismiss—he would file a lawsuit on the farmer’s behalf against DuPont and three years later mount a successful class action suit on behalf of other West Virginians exposed to the contamination.

Bilott’s litigation is transcendent in the sense that the research he did for his cases uncovered the hidden history of how the dangers of “PFAS” (the common acronym for the long list of “forever chemical” variants) were discovered. He also uncovered and documented how those dangers were suppressed, work that set the stage for a tide of civil lawsuits including one filed by the State of Washington last month. Bilott was recognized with a prestigious “International Right Livelihood Award” in 2017.

There are countless lessons and plenty of drama in Exposure, which became the basis for the 2019 film Dark Waters, featuring Mark Ruffalo in the role of Bilott. But the central, ominous lesson—which Exposure repeatedly circles back to—is that our framework of landmark environmental and public safety laws (i.e. the Clean Water Act (1972), the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974), the Toxic Substances Control Act (1976) and federal “Superfund” cleanup law (1980), is painfully inadequate to protect Americans from ourselves.

It was not just Earl Tennant and his neighbors who were unwittingly exposed to the same chemicals that devastated Tennant’s cows. It was millions of Americans, perhaps more than 100 million, who’ve already been exposed to one or more variants of perfluoroalkyl and polyflouroaokyl substances (PFAS) like the one that DuPont secretly disposed of in a supposedly sanitary landfill upstream from Tennant’s farm.

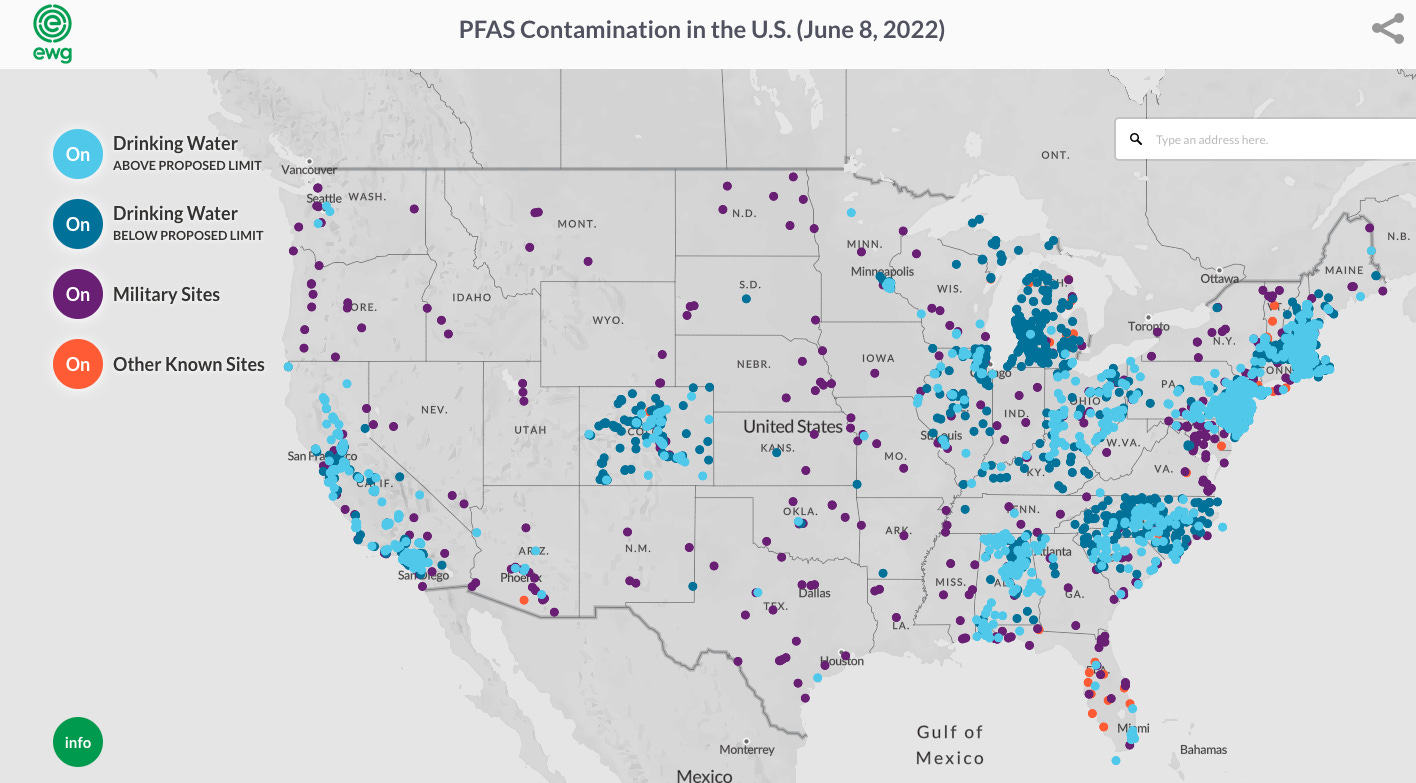

Map compiled by the Envirionmental Working Group illustrating positive results for PFAS contamination in US drinking water systems as of June of 2022. (Link to interactive version.)

“Corporate Greed” is in the subtitle of Exposure. But, through his extraordinary experience, Bilott’s story has an even broader reach. To be sure, corporate greed wears the silk ties and wing-tipped shoes. It not only has access to the best legal talent on the market, but the premier public relations firms, the best connected lobbyists, and—through campaign contributions—politicians who control the purse for governmental agencies charged with enforcing environmental and public safety laws. But Exposure also shines a light on the broader social and economic culture that greed affects. As the largest employer in Parkersburg, the importance of the Dupont payroll is well understood in Wood County. So when Earl Tennant filed his lawsuit, he and his family became outcasts to many of their neighbors—seen as a threat to local jobs and the local economy.

Bilott writes about this as well as his own experience of being treated as something of a turncoat by his peers in the corporate legal defense community. It gets to both the text and texture of our problem—our real-life and often high stakes conflicts between public health and private wealth.

I learned the term “regulatory capture” early in my career as an environmental reporter. It’s a bland description for how state and federal regulation is undermined—especially in poorer states like West Virginia—by the practice of offering higher corporate salaries to competent, underpaid regulators, thereby weakening the capacity of those agencies to regulate businesses like DuPont. In the worst cases, the state agencies actually provide public relations cover for polluting industries.

It’s not just a problem in poor, conservative states like West Virginia.

When I started my reporting on the Hanford plutonium factories in the early 1980s, one of my sources sent me a remarkable document from a government consultant associated with Los Alamos, the famous government nuclear weapons laboratory in New Mexico. Entitled Some Political Issues Related to Future Special Nuclear Materials Production it was offered candid advice on how to thwart local opposition to expanding the production of plutonium for a new generation of nuclear weapons.

Apart from being the main ingredient in most modern nuclear warheads, plutonium is highly toxic. Its production results in large volumes of hazardous nuclear and chemical byproducts. At the time the paper was written (1981) the government and its contractors were still keeping secret the reports about the worst Hanford pollution, including the fact that plutonium production operations had exposed my mother’s family and other family’s downwind and downstream from Hanford to radioactive water and radioactive milk.

The premise of the Los Alamos paper is that the government had to be prepared for public opposition to new plutonium production. Under the heading “Local and Regional Citizen Reaction” the report stated:

“The above activities [increased plutonium production] would hardly be unwelcome in the communities that surround existing Federal reservations at Hanford and Savannah River [on the South Carolina/Georgia border]. The prospect of additional economic well-being for these communities, which has been called ‘the halo effect’ can be expected to more than offset any qualms about about radiation risk or other fears.”

In Hanford’s case, that turned out not to be true. Once the public became aware (as a result of repeated demands by journalists and activists) of the dangerous emissions and continuing hazards, the ‘halo effect’ dissipated, and plutonium production all but ceased by 1990.

The problem is it took forty years for Hanford to come clean, so to speak, about when and how it contaminated my mother’s (and thousands of other vulnerable children’s) milk with radioactive iodine. (She contracted hypothyroidism, likely as a result).

What’s shocking about the Dupont releases that Bilott painstakingly uncovered is they were not from a secretive nuclear weapons plant in the 40s or 50s, but from a modern chemical plant more than two decades after federal laws had come on the books to ostensibly prevent such tragedies. Bilott ultimately won judgements not just to compensate for his clients’ injuries but for “punitive” damages that punished DuPont for suppressing evidence of the pollution and of its own awareness about the potential for causing a variety of health problems, including cancer, as a result of occupational and environmental exposures.

Other civil lawsuits are now in progress, including the one filed by Washington state Attorney General Robert Ferguson just a month ago, naming DuPont, 3M and 18 other “forever chemical” manufacturers. A central allegation in Washington’s civil complaint, and others, is that the manufacturers knowingly hid the health risks of the chemicals from regulators and the public.

The fact that this is happening—and that we’re still struggling to get our minds and hands around the problem—is a verdict on our failure as a society.

It is terrific, to be sure, that Bilott’s saga—like Erin Brockovich’s inspiring fight to expose deadly hexavalent chromium pollution from a Pacific Gas & Electric plant in California—have become subjects for popular films. It’s not terrific that the dramatic tension in the films is forged against the reality that the people doing the truth-digging and litigating are up against such overwhelming odds.

That the decks are still stacked in favor of corporate profits at the expense of public welfare is not at all entertaining. It’s frightening. If our laws are working properly there should be only a trickle of civil lawsuits against polluters, not the torrent we’re seeing now because of the widespread and preventable contamination with the “forever chemicals.”

•As a footnote on this subject—given the close proximity between the PFAS contaminated groundwater on the West Plains of Spokane County and the City of Spokane—I thought I should underscore that there is no substantial connection between the West Plains aquifer(s) and the Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie aquifer that is the source of the City of Spokane’s drinking water. (Indeed, the SVRP aquifer is also now the source of the City of Airway Heights’s drinking water, inasmuch as it is being delivered to Airway Heights via pipe from Spokane) I’m including the table, below, from the City of Spokane’s most recent drinking water tests for PFAS. The levels observed are below the state’s action levels.

•Finally, I need to register an important correction to Sunday’s post on this issue. The first hazard of writing about the “forever chemicals” is acronym fatigue. I had mistakenly designated the acronym PFOA as the cover term for the incredibly broad suite of “perfloroalkyl and polyflouroalkyl” chemicals, with more than 1,000 variants, that make up the “forever chemicals” at issue. The correct acronym is PFAS, which is a stand-in for “per- and polyflouroalkyl substances” encompassing a broad range of synthetic molecules with carbon-flourine chains. PFOA stands for perfluorooctanoic acid which is one of the two most common groups of PFAS. (It was a version of the PFOA molecule that was implicated in the releases from the DuPont Washington Works plant in West Virginia that led to the litigation that Robert Bilott writes about in Exposure.) The other common group designation is PFOS which stands for perflorooctane sulfonic acid.

I apologize for any confusion, including my own.

—tjc