Sunday's postcard, and a primer on the ominous, synthetic chemical that contaminates drinking water from coast to coast

June 25, 2023

Children chilling at Hoopfest

Six years ago the City of Airway Heights—on the West Plains just seven miles from Spokane—made a disturbing discovery. Lab analysis of its municipal water revealed the presence of a class of synthetic, toxic substances—“per- and polyfluoroalkyl” chemicals—commonly referred to by the acronym PFAS. The city stopped pumping groundwater and swiftly arranged to pipe water in from Spokane.

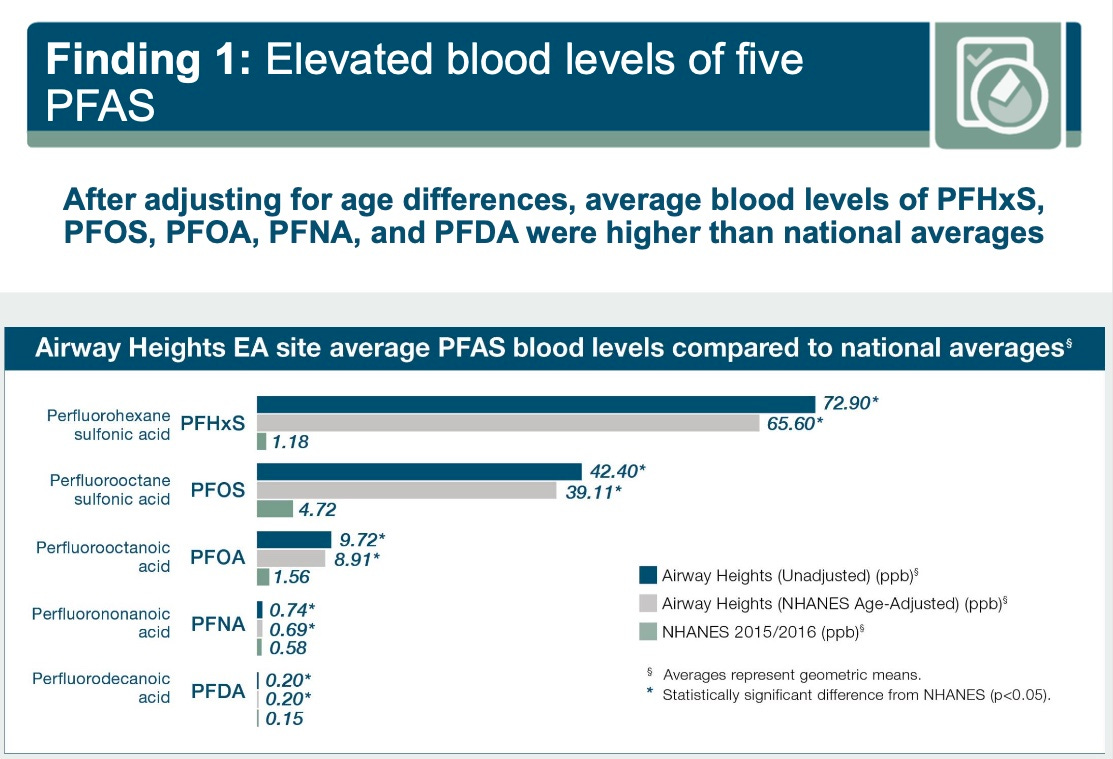

The shadow of the exposure remained—blood testing by the federal Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry (ATSDR) found that all of the more than 300 Airway Heights water users who took part in a voluntary blood survey still had elevated PFAS in their bodies two years after their consumption of the contaminated water had ceased. For one of the variants tested—PFHxS—blood levels were 60 times higher than the national average.

It was and remains a startling local story. But the West Plains pollution is just another dot on the map of U.S. drinking water sources fouled with PFAS resulting in public exposures to potentially harmful levels of a fiendish and resilient blend of toxins. Epidemiological studies link exposure to an increased risk for a variety of health effects, including altered immune and thyroid function, liver disease, lipid and insulin “dysregulation,” kidney disease, birth defects and developmental outcomes, and cancer.

Nationally, the breadth of the problem is astonishing. Perhaps the most disturbing fact about perfluoroalkyls is their immunity from regulation—literally for decades. The variants (of which there are literally thousands) are known as the “forever chemicals” for their persistence in the environment and in the human body. But it also seems as though it has taken forever for them to be regulated by federal environmental and health agencies, as you would expect given that indications of the chemicals’ toxic effects were recognized more than forty years ago.

Although the main pathway of human exposure to PFAS variants is via drinking water, because of their remarkable ability to repel water and grease the compounds are present in a wide variety of consumer products including grease-resistant papers (e.g., fast food containers/wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, pizza boxes, candy wrappers); stain resistant carpets and upholstery in homes and vehicles; water-resistant clothing and footwear, cleaning products, personal care products (e.g., shampoo, dental floss, cosmetics such as nail polish and eye makeup); paints, varnishes, ski wax and sealants. The PFAS groundwater contamination on the West Plains has been attributed to “aqueous film forming foam” (AFFF), which was widely used for decades at airports and military air bases, including Fairchild Air Force Base, for aviation firefighting and training exercises.

Locally, the progress toward investigating the breadth of the PFAS contamination problem on the West Plains has been driven by litigants including the Kalispell Tribe which filed suit in 2020 against 3M, other AFFF manufacturers, and the U.S. government, after the groundwater it relied upon for its Northern Quest casino in Airway Heights was contaminated. The West Plains Water Coalition (created earlier this year) and supporting, non-profit organizations like the Spokane Riverkeeper have also become involved.

Washington is now at the forefront of states who’ve grown impatient with the slow pace of federal action to regulate forever chemicals in groundwater and soils. In November 2021—in response to the PFAS groundwater contamination problem on the West Plains, near Fort Lewis, the Whidbey Island Naval Air Station, and other locales—the state board of health promulgated State Actions Levels (SALs) between 9 and 345 parts per trillion for five PFAS variants.

The state is also now pursuing aggressive legal action. Last month, Washington Attorney General filed a lawsuit in King County seeking damages against Dupont, 3M and 18 other manufacturers of PFAS chemicals used in fire suppressing foam like that which is implicated in the West Plains contamination. The suit alleges the “companies knew for decades about the serious risks these chemicals posed to humans and the environment.”

A bit of history. As lawyer and author Robert Billott recounts in his 2019 book Exposure the discovery of the first “forever chemical” compound by Roy Plunkett, a young Dupont scientist, was a happy accident, at least for Dupont. Assigned the task of inventing a new refrigerant, Plunkett inadvertently created a very slippery, inert and incredibly stable substance. Polytetrafluoroethylene. We know it as Teflon.

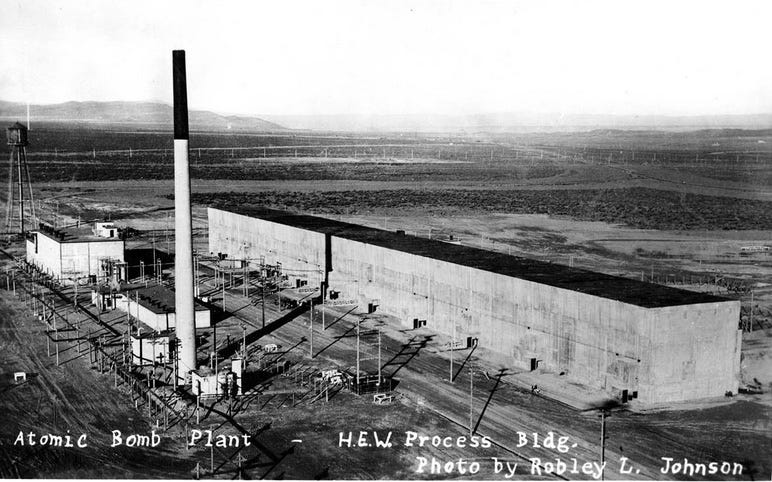

“Plunkett’s discovery was a timely one,” Billott notes, because it was right before World War II and the secret assignment Dupont was given by the Army Corps of Engineers’ “Manhattan Project.” Specifically, Dupont was assigned to build a full-scale plutonium plant at the“Hanford Works.” The interior of the plants—where plutonium was chemically separated from irradiated uranium slugs—was a brutal environment, involving intense radioactivity, powerful acids and solvents. But it was an environment that Teflon-coated seals and gaskets could withstand.

Hanford’s “T” plant, part of DuPont’s Manhattan Project work at Hanford to produce plutonium during World War II

A bit of chemistry. Naturally occurring organic molecules—the building blocks of life—typically incorporate bonds of carbon and hydrogen atoms. In the synthetic PFOAs though, flourine supplants hydrogen, creating incredibly resilient chains of carbon-fluorine. This resiliency (it takes temperatures exceeding 1,100 degrees celsius to destroy PFASs) is what gives them their persistence in the environment. Unfortunately, the compounds also bio-accumulate. Once ingested, PFOAs can be retained in our bodies for several years. For example, the PFHxS compound that turned up in such large concentrations in the ATSDR blood study of Airway Heights residents has a biological half-life of 8.5 years—which means that even if you stop ingesting or being exposed to it by other means, the amount in your bloodstream only goes down by 50% every 8.5 years.

A bit of epidemiology. As with low doses of ionizing radiation, the relationship between exposure to low levels of PFAS (commonly reported in parts per trillion) and health outcomes is what epidemiologists often refer to as “stochastic” effects. What this means is there are no precise, smoking gun correlations between frequent low level exposures to a toxic substance and the onset of a disease in a specific, exposed individual. Rather, it means that the magnitude of the exposure elevates the probability of one or more health effects—such as high blood pressure or infertility, to outcomes like cancer that can outright kill us. As I wrote in Burdens of Proof—a 1997 book examining the limitations of environmental epidemiology—“it is in a sense, death by lottery and burial in a deep pile of statistics.”

As the state’s lawsuit alleges (and Billott’s Exposure book details through his experience litigating landmark PFAS cases) the manipulation of science and purposeful sandbagging of state and federal regulatory processes by powerful corporations has deeply undermined basic human rights and the democratic process we hope we can rely upon to protect public health and the environment. I’ll explore that next.

—tjc

Good primer, thank you.