Tuesday's postcard, and what a Seattle Times investigation reveals about the poisoned groundwater west of Spokane

October 31, 2023

Larch in the rimrock below the Wanapum wall of the West Plains in Riverside State Park

Bad Water and secrets in the airsick bag

Since I started reporting on the West Plains’ “forever chemical” fiasco in June I’ve been to several gatherings and heard from a number of people whose lives have been affected by contamination in their drinking water. These are people who live down-gradient from Fairchild Air Force Base and Spokane International Airport.

Some have buried spouses and other family members. Some have been forced to spend considerable sums of money to test their well water for dangerous synthetic chemicals, and then had to scramble and pay even more to have filtration systems installed for their taps.

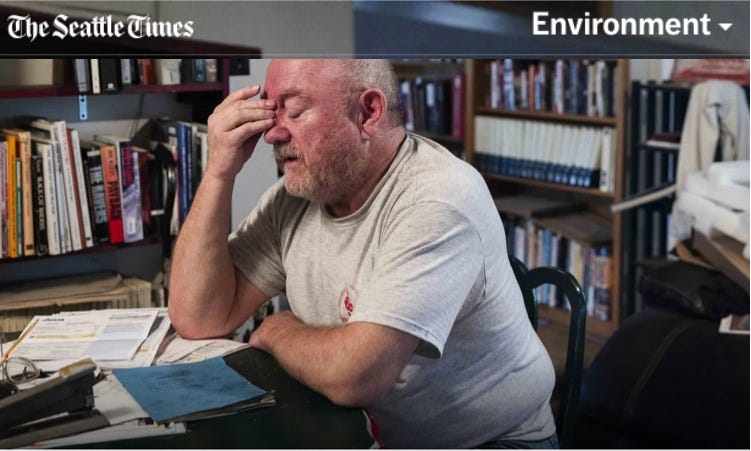

One person I haven’t met, at least not yet, is David Snipes. It’s Mr. Snipes’s photo on the cover to the Seattle Times feature article: PFAS is in the groundwater west of Spokane. What’s known about the contamination is only growing

As Times’ journalists Manuel Villa and Isabella Breda report, Snipes and his family drank and watered their cows on spring water up until the 1990s. The spring is located a mile or so from Spokane International Airport (SIA). SIA, we now know, is one of two large airports on the West Plains that are sources for so-called “PFAS” pollutants. These are the highly toxic synthetic chemicals which constitute what, by any definition, is a widespread contamination problem on the plateau just to the west of the City of Spokane. Snipes is one of thousands of people, at least, who know or suspect they’ve been exposed to PFAS via drinking water. They want answers and many have organized to try to get answers, and help.

It is a credit to the Seattle Times and its journalists that this story exists and exists in a form that reminds us what a large, solvent and committed newspaper can do, both in print and on-line. The package includes a poignant and intimate video, “Stop Drinking the Water” that captures the deeply emotional loss of loved ones and the lingering questions and frustrations of suspected poisonings. It also includes first-rate graphics to help illustrate the complex story of why PFAS groundwater contamination is such a fiendish problem on the West Plains.

Frankly (and with appreciation for the Times’s efforts), it’s a hard story to tell, even before you add the human decisions and consequences.

For starters, PFAS {Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances) are a fiendish poison to grasp. Consisting of chains of carbon and fluorine atoms, PFAS are a human creation dating back to a discovery in the 1940s that they have miracle-like properties for water, stain protection, and resistance to stickiness that made it an ideal ingredient for Teflon and other widely used industrial and consumer products. There are well over 10,000 variants of PFAS and some were used in aviation fire-fighting foams used—primarily in training exercises—at commercial and military airports like Spokane International and Fairchild respectively.

Marketed by DuPont, 3M and other industrial giants, PFAS chemicals have been a veritable gold mine for companies and shareholders. This helps explain why it has taken literally decades since the discovery of PFAS’s fiendish health effects on animals and people to regulate their use and disposal. If you want a glimpse into this world of corporate power politics, read Robert Billot’s Exposure.

The primary route of exposure (as is the case on the West Plains) is via contaminated drinking water and, yet, as I write, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has still not issued its final rule. It is proposed at a level quantified in parts per trillion—basically at the detection limit for PFAS. In 2021, Washington state set State Action Levels (SALs) for five of the major PFAS variants at between 345 and 9 parts per trillion.

Again, the complexity of the story is an unavoidable problem. I’ve just used 3 paragraphs, squeezing words together, to offer a brief synopsis of the poison. If we were dealing with lead or arsenic I could have done it in one paragraph. And, by the way, the federal drinking water standard for arsenic is 10 parts per billion, three orders of magnitude higher than the proposed standard for PFAS.

The other baked-in complexity is West Plains geology which is probably why the Seattle Times story starts with a geology tutorial leading into its very helpful graphics, illustrating the problem.

The gnarly hydrogeology of the West Plains is remarkably different than that of the Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie aquifer which provides the City of Spokane with abundant and remarkably clean water. The Ice Age floods were involved in creating both realms—laying down a thick bed of cobbles for the Spokane aquifer to gush through, but viciously colliding with the Wanapum and Grande Ronde basalt flows as the floodwaters overflowed the Spokane gorge onto the West Plains.

Incredibly, the force of the floods created enormous water falls and vortices that drilled deeply into the basalts. These natural borings left so-called “paleochannels” filled with cobbles that are the ingredients for a much more porous and groundwater-friendly medium than is present in the basalts. In short, if contamination enters the paleochannels it can move quickly and contaminate groundwater miles away from the source of the contamination. And because the paleochannels are quite deep (more than a hundred feet in some places), they can deliver contamination to groundwater tapped by wells drilled deeply into the basalt aquifers.

These two factors—the poison and the geology—set the stage for the West Plains’ liquid nightmare

Miles away from Fairchild and SIA, Marcie Zambryski talks about her PFAS-contaminated well and the lives claimed by cancer in her household. Screenshot from the Seattle Times’s video “Stop Drinking the Water”

I’ve researched and written about groundwater contamination at Hanford and the Savannah River Site in South Carolina. Both are home to contaminated ground and surface waters caused by the witches brew of chemicals and radionuclides involved in distilling plutonium for nuclear warheads. But here’s a sobering thought: it’s entirely possible that PFAS contamination on the West Plains has already affected and endangered the lives of more people than those who’ll ever be exposed to contaminated groundwater at Hanford and Savannah River—combined.

It is against this backdrop that the Seattle Times introduces us to David Snipes and the human part of the problem. First, I should make very, very clear that Mr. Snipes is not the problem. To the contrary—by sharing his story with the Times’ reporters, he very much helped to reveal its essence.

He did so after learning from media accounts that PFAS had been found in groundwater at and near Fairchild Air Force Base. In short order, it was also reported that PFAS had been discovered in groundwater being pumped and fed into the distribution system for the nearby City of Airway Heights (population 10,700). The city quickly turned to Spokane to secure uncontaminated water. (By that time, however, a federally-funded study would later show that people consuming Airway Heights drinking water had accumulated PFAS in their bloodstream exceeding 65,000 parts per trillion—four orders of magnitude higher than EPA’s proposed drinking water standard.)

According the Seattle Times story, Mr. Snipes was concerned enough about the reported contamination that, in May of 2017, he sent an email to Larry Krauter, the Spokane International Airport’s CEO, asking if the SIA had ever used fire-fighting foam containing PFAS.

SIA is a joint public venture of the City of Spokane and Spokane County and Krauter is its leader. He replied the next day, the Times reported, with an email stating that “(f)ortunately, we do not have any kind of situation here…accordingly, we do not have cause to be interested in testing groundwater.”

Yet, four days later, it turns out the airport did test its groundwater. When it did so (as I reported in early July) it found PFAS contamination. Only it didn’t tell David Snipes or local and state health officials about it—for six years.

That potent silence—the Times reports that neither Krauter nor Spokane Mayor Nadine Woodward responded to the newspaper’s request for interviews—speaks for itself.

When the PFAS contamination at SIA was finally revealed earlier this year—thanks to a citizen on the West Plains who filed extensive public records requests with SIA—it had a predictable effect on the West Plains community, and especially those who are still dependent on well water. It only exacerbated their sense that government has betrayed them, guarding its own interests at the expense of their well-being.

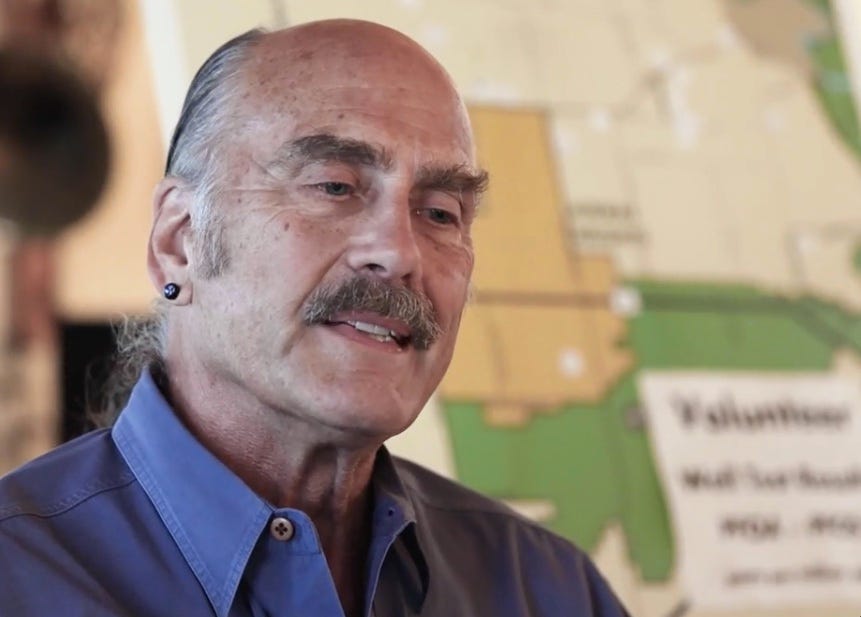

John Hancock speaking to Seattle Times journalists in a screenshot from the Times’s “Stop Drinking the Water” video.

“The airport’s mission is really clear, as is the mission of the Air Force base” says John Hancock a lead organizer and spokesperson for the West Plains Water Coalition citizen group. “And nowhere in those missions does public safety for the neighbors earn even a mention in fine print. So it’s a lack of community stewardship, which is a lack of foresight by the owners and top managers of those missions.”

To be sure, there are still plenty of grievances aimed at Fairchild Air Force Base for its share of the PFAS contamination and what many consider an inadequate response to providing assistance to well owners and small water systems with PFAS contamination. But at least the Air Force admitted it had a problem when it found it had a problem. It alerted an official with the Spokane Regional Health District and cooperated in the urgent efforts to respond to the crisis.

In contrast, the Spokane Airport appears to have done nothing to alert health officials to the groundwater contamination on its property, and would likely still be stonewalling were it not for the revelations in the documents turned over earlier this year in response to the records requests. David Snipes told the Times he feels lied to by SIA “and when the government lies, I don’t like it.”

Perhaps the most positive outcome to the forced disclosure of the airport’s PFAS contamination problem is that it opened the door for Washington state’s Department of Ecology to exercise its jurisdiction under the state’s Model Toxics Control Act. Ecology gains entry because SIA is a state facility, whereas FAFB—as a federal facility—is primarily accountable to the federal EPA for addressing the PFAS contamination and other pollutants (such as the solvent TCE) that were already being addressed by EPA under the federal Superfund program.

In mid-August, Ecology formally notified SIA that it was being designated a “responsible party” under the state law and the airport must comply with a state-approved cleanup plan guided by a detailed site investigation study. Currently Ecology and SIA are in negotiations to develop a draft state order for site investigation and remedial action at the airport. The draft will be available for public comment in early 2024.

On December 14th the West Plains Water Coalition will be hosting a meeting to brief the public about the draft order and how citizens can comment and otherwise participate in finalizing the order. Ecology has confirmed that representatives from the agency will participate in the meeting. John Hancock assures me that officials representing SIA will be invited to attend as well.

—tjc

Editor’s note: the article was revised on 11/2 to report that the draft state order for site investigation and remedial action will be available in early 2024 and not December 2023.