June 4, 2024

Twilight at “The Feathers,” western Grant County

On the ropes of a toxic scandal

There are ordinary public relations disasters. Then there’s the sort that the Spokane International Airport is still a wing and a prayer from being able to escape. The troubling gravity consists of stubborn facts.

Put to story it happened this way. A bit more than seven years ago, Fairchild Air Force Base let it be known that it had a serious groundwater contamination problem. It had found variants of PFAS—the so-called “forever chemical” that, until recently, was used in aviation fire-fighting foam—in its monitoring wells. In short order, it also found that the dangerous chemicals (so dangerous it is regulated in parts per trillion) had migrated off the base and contaminated drinking water wells, including wells supplying water to approximately 10,000 people in the nearby City of Airway Heights. It made the newspapers. It aired on TV.

One of those who noticed, with alarm, was David Snipes. As the Seattle Times reported last fall, Snipes is a 70 year-old farmer who raises cattle not far from the runways of Spokane International Airport (SIA). He wanted to know if water he, his family, and their cows had been drinking for years had been contaminated. So on May 18, 2017 he sent an email to Larry Krauter, the CEO at SIA which, as a joint venture of the City of Spokane and Spokane County, is a public entity. Krauter wrote back assuring Snipes:

“Fortunately, we do not have any kind of a situation here at SIA that is similar to what is occurring over at the base and in Airway Heights…”

Perhaps as a result of Snipes’s query, SIA then decided to test its groundwater. And in three of the four wells it tested, it found high levels of PFAS. When SIA sampled again in 2019, it found levels as high as 5,200 parts per trillion (ppt), greatly in excess of the federal interim action level of 70 ppt. (In April of this year, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), finalized the federal drinking water standard for most PFAS variants at 4 parts per trillion).

SIA never got back to Snipes with the new information-nor anybody else for that matter. The documentation of SIA’s PFAS problem only came to light last year as a result of a citizen activist’s public records request.

To be sure, there is a lot going on, now, to deal with PFAS on the West Plains. On the surface the vibe is American potluck grounded in what some would call “Spokane nice.” But barely beneath the surface there is an unmistakable edge of frustration and exasperation. At times, there are open flames of distrust. All three were present last night shortly after County Commissioner Al French took to the podium.

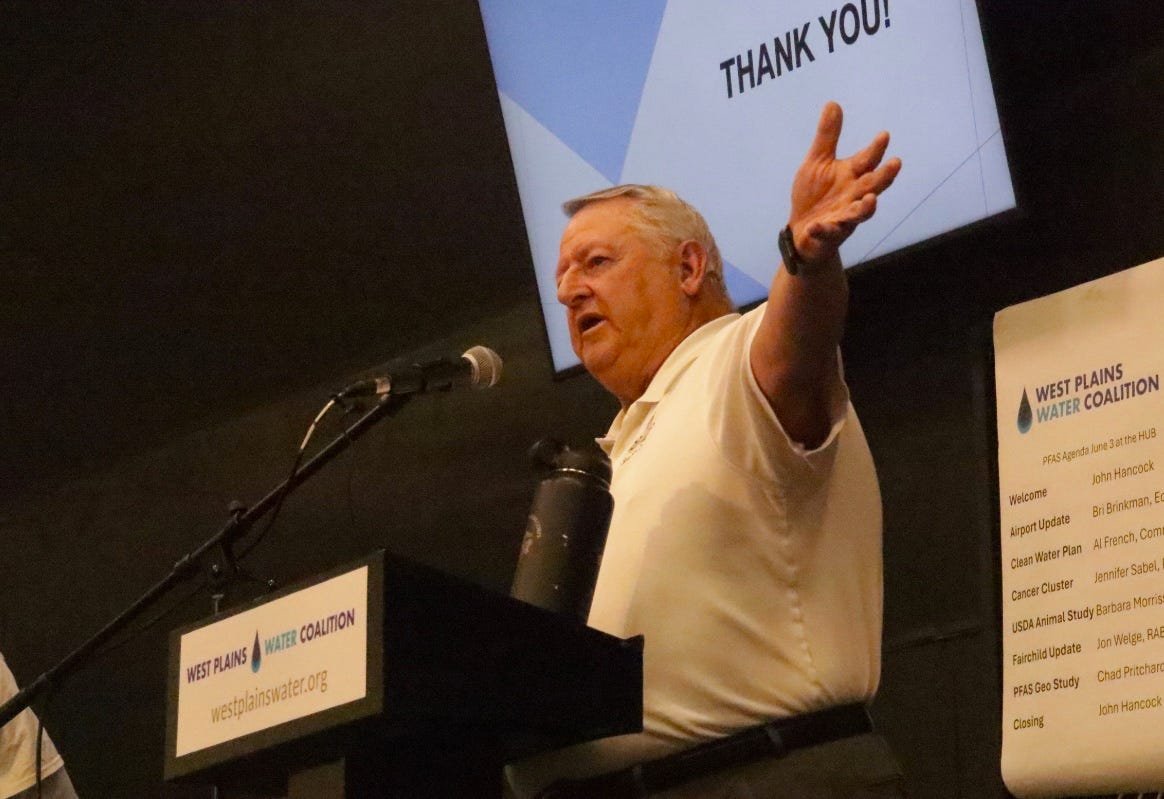

County Commissioner and veteran Airport board member Al French taking questions before a restless audience Monday night.

These are a hard facts to ignore given the weight of national press about the looming PFAS in drinking water crisis not to mention the flurry of activity right next door, so to speak, when FAFB was (and still is) struggling to get clean water to those whose wells have been contaminated with PFAS emanating from the base. In November 2021, Washington’s Board of Health announced the state’s new “action levels” for PFAS in drinking water, setting the bar at 10 to 15 ppt for most PFAS variants. And, still, SIA failed to disclose the high levels of PFAS—exceeding the state’s new action levels by orders of magnitude—in its groundwater.

One of those who knows this history very well is Craig Volosing.

Volosing is the president of the Friends of Palisades, a neighborhood-based conservation organization rooted just to the northwest of SIA where scores of private wells have been contaminated with PFAS. He was in the audience last night at a meeting in Airway Heights where several speakers had been invited by the West Plains Water Coalition to address different facets of the PFAS problems. To be sure, there is a lot going on, now, to deal with PFAS on the West Plains. On the surface the vibe is American potluck grounded in what some would call “Spokane nice.” But barely beneath the surface there is an unmistakable edge of frustration and exasperation. At times, there are open flames of distrust. All three were present last night shortly after County Commissioner Al French took to the podium.

At the start of the program, the coalition’s president, John Hancock, reported Krauter and another SIA executive had declined invitations to appear at last night’s event. But Hancock had also invited French, currently Spokane’s longest-serving elected official, and arguably its most influential politician. French is running for re-election this year. He accepted the invitation.

French has been a stalwart on the SIA board for many years, and a leader in “S3R3” Solutions, a non-profit formed to recruit and service business interests in the “West Plains Airport Area.” French is chairman of S3R3. SIA CEO Krauter is vice-chair. There is a paper trail of evidence, supported by on the record interviews, that French delayed and nearly succeeded in killing a key groundwater study crucial to securing a better understanding of the scale of the contamination, at and beyond the airport.

In retrospect, there’s little question the study would have uncovered the PFAS plume(s) from the airport. Indeed, in his 2017 email to Krauter, David Snipes noted that the wetlands on his property feed the Garden Springs creek that emerges near the Finch Arboretum in west Spokane. Sure enough, one of the delayed study’s first findings—made public just a couple weeks ago—is that David Snipes had every reason to be concerned: there is elevated PFAS in Garden Springs creek.

Tarmac at Spokane International Airport, looking north from main terminal

Last night and in other recent public appearances, French now presents himself as a champion of that same study. He asks his audiences to look forward and not backwards. That doesn’t sit well with those, like Volosing, who were alerted to French’s foot-dragging years ago and now demand accountability.

Questions were limited last night, but Volosing made sure his was one of the first hands to go up.

“I know you certainly don’t want us to be reliving any history,” Volosing told French. “But one really burning question would help us understand how we got here.”

He then walked French through the history and argued that French was in the best position—as County Commissioner—and board member on both the regional health district and airport board—to observe and influence the process.

“Will you please help us understand what guided keeping a lid on this?”[the airport’s PFAS contamination] “Keeping it from the public? Keeping it from downstream well owners?”

Volosing continued, referencing the delays in the groundwater study.

“What happened where we could have utilized this process and having it begun five, six years ago, and have a whole bunch of remediation underway by now? Why did you keep it under wraps for so long?”

A wave of applause rose and rippled through the audience.

French absorbed the question and the applause for Volosing. He then said, in essence, that he couldn’t remember very well, but that he was having staff—at both the airport and the county—investigate his conduct.

French put it this way:

“So in the last seven years, this has been a evolving topic. And we've learned a lot from the science and from a variety of different sorts of-- so to answer that question, I now have staff that's going back through the last seven years of my activity at the county and involvement with the airport as well as others. And so we are going to be coming forward with a record, with documents to back it up, so that we can answer that question. Because quite honestly, I don't remember everything that happened seven years ago. But we do have records that can identify that. And we're going to make it public so that you will know everything that I knew at the time.”

“And again,” he continued, “I'm one person on an airport board of seven. And the airport is located in the city. There are three other elected officials that have the same information that I did and also not coming forward. And there's reasons for that. And so we will provide that for you.”

“And what are those reasons that it has to go to this big investigative process that's inside your own office?” Volosing interjected.

“And there's legal reasons for that that I cannot speak to at this point.” French replied. “And I'm working to try and get the freedom to be able to talk about those.”

Volosing then asked a followup, which was more of a statement than a question.

“Our investigation shows that the primary reason that you have kept a lid on this is financial. It has to do with all the wonderful big money deals going on in property development around the airport. And you didn't want any bad news to screw up those deals and devalue the property. You have played to your constituents and those who fund your campaigns rather than consideration for the downstream people, knowing full well for years.”

To which French replied: “Well, you're certainly entitled to your opinion. I think what you'll find is the record doesn't support that. And so we'll be coming forward. And you're all entitled to an opinion, but you're not entitled to your own facts. And we'll be coming forward with the facts.”

With that he left the podium, to a cordial smattering of applause.

As he began to dismount the stage, a woman from the audience shouted:

“You said you're coming forward with this information. Can you give us a timeline on that?”

His reply: “Probably within the next two or three weeks.”

French asking the airport and county staff to help him investigate himself is noteworthy. It does look back at a crucial period of decision-making, but it is hardly independent, especially given French’s repeated excuse that answering questions about his and the airport’s decision-making on PFAS is curtailed for “legal” reasons.

As I’ve reported previously, quite apart from Ecology’s intervention under the state’s Model Toxics Control Act to compel and devise a cleanup plan for SIA, there is the short-term emergency to better identify and assist well owners whose water is presently contaminated with PFAS. In February, Ecology and EPA teamed up to in February to sample more than 300 wells in the zone north of SIA and east of Fairchild’s response area. These were residents who weren’t eligible for testing and remediation under the Fairchild program. The results—via EPA sampling and testing—were striking, with 172 wells found with PFAS above action levels. It has been the state’s role to deliver bottles of clean water to those whose wells are contaminated.

The agencies subsequently announced that funding is available to extend the program to another 125 well owners, beginning thus month. Last night Ecology’s Bri Brinkman made an added and urgent appeal to well owners who’ve had their wells tested to provide their data tables to the agency, as the data are vital to the science of better understanding where and how contaminated groundwater is moving through the highly complex West Plains aquifer system.

—tjc

author’s note, this article was corrected on June 13th to fix an attribution error in the dialogue between Craig Volosing and Commissioner French.

Reporting on the West Plains “forever chemicals” saga is provided free as a public service. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription to The Daily Rhubarb by clicking on the tab below.