Male Northern Flicker taking flight above the Bowl & Pitcher, Riverside State Park

Liquid Anxiety

At 6:26 Tuesday night there were no empty seats inside the HUB meeting space just off Highway 2 in Airway Heights. The single-story hall slopes toward a low stage where a drum set without a drummer awaited a happier crowd than the one that filed in out of the rain.

Well over 200 people had come to hear the latest news about what an ad hoc team state and federal officials had found in their drinking water. As many feared, the news about the water isn’t good. By the time it was delivered more chairs had been carried in to fill the space in front of the drums. The crowd also spilled over into the hallway at the back of the room.

In a more just world the speakers facing the restless crowd would have been scientists and top executives from the two mega-corporations who’ve made billions of dollars from the invention (Dupont) and world-wide sale (DuPont and 3M) of products containing PFAS—the “forever chemical” used in teflon, cosmetics, water resistant apparel and a myriad other consumer products, even dental floss. For a half century 3M had marketed Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) a PFAS-laden retardant tailored to suppress aviation fuel fires. Until recently, PFAS foam was extensively used—both at Fairchild Air Force Base and Spokane International Airport (SIA)—in firefighting training. The result is that groundwater has been contaminated with PFAS chemicals throughout much of the West Plains, the plateau southwest of Spokane where groundwater flows in and between layers of fractured basalt.

A snapshot of the problem comes from the City of Airway Heights, population ~11,000 which, until the spring of 2017, pumped aquifer water to its residents. Those who drank Airway Heights water before the contamination was detected in 2017 received alarmingly high large doses of PFAS. Two years later, the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) drew and analyzed blood from more than 300 Airway Heights residents. On average, those tested had one or more PFAS variants in their blood, at levels more than ten times the national average. For one of the PFAS variants—Perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), the average concentration in blood was over 65 parts per billion.

That may seem like a small number. But last month, the EPA announced its new “maximum contaminant levels” (MCLs) for PFAS in drinking water. The revised standard for PFHxS is 10 parts per trillion. In other words, even after being off contaminated water for two years, the tested Airway Heights residents had PFHxS in their blood at levels averaging 6,500 times the new drinking water standard.

Editor’s note, reporting on the gnarly West Plains PFAS story is provided free at Rhubarb Salon, as a public service. If you’d like to support this and other reporting with a paid subscription please do so by clicking on the tab below. And please share this post…tjc

The EPA/Ecology sampling area (left), and EPA sample collection in March (images from EPA)

PFAS is a stochastic poison, which means its effects occur by chance. In general, the likelihood of a person getting sick or dying from ingesting PFAS increases with dose, but the severity of the health effect, including cancer, is not necessarily dose dependent. For one person, even a small but cumulative dose can instigate an endocrine (i.e. damaged thyroid) or carcinogenic injury; even a fatal outcome. In another person, a much larger dose may have no discernible effect whatsoever.

If this unnatural family of chemicals is cruel, so are some of the human actors. The day before the meeting at the HUB, the Pultizer-Prize winning journalism project, Pro Publica, published a riveting investigative story, Toxic Gaslighting by Sharon Lerner. Its central character is former 3M scientist Kris Hansen. As a young researcher in her late twenties, Hansen was asked by her 3M supervisor to analyze human blood samples from the general population for PFAS. She was surprised to find how pervasive the detections were. Her discovery was very unwelcome news at 3M. What Hansen didn’t know is that her predecessors and superiors had already discovered, and were keeping secret, the evidence from animal studies of just how toxic PFAS is. It was only years later that Hansen learned just how much information about PFAS health effects had been suppressed by 3M.

The story doesn’t end well: not for Hansen (who eventually lost her job), not for literally thousands of U.S. communities with serious PFAS contamination, and not for 3M, which, like DuPont, is now facing a sea of expensive lawsuits for alleged misconduct and damages caused by PFAS exposure.

Closer to home, the anxiety about what’s in the water beneath the West Plains swirls with smoldering frustration at Air Force and local officials.

In general, the Air Force is not in the hospitality business. Although it acted with reasonable dispatch to secure clean water for Airway Heights after its PFAS contamination was discovered seven years ago, it has struggled to serve the 107 private well owners—spread over more than 20 square miles—deemed eligible for federal assistance due to high levels of PFAS in their well water. The number of West Plains well owners eligible for direct assistance via the Fairchild program is likely to double as the new EPA drinking water standards go into effect.

The frustration with Spokane-area officials is even more intense, and for good reason. Public records obtained last year show the airport’s managers were made aware (2017) of PFAS contamination in the airport’s groundwater. They chose not to disclose it, neither to SIA’s neighbors nor to state and local environmental and public health agencies. Public records also corroborate county sources who say County Commissioner Al French—a longstanding and prominent member of the SIA board of directors—hamstrung efforts to secure state funds for a groundwater surveillance project capable of detecting PFAS in groundwater near the airport. The delayed study is now just getting underway. But there’s no question that the delay—along with SIA’s failure to disclose the PFAS in its groundwater monitoring (2017 & 2019—prolonged preventable human exposure to PFAS in private wells whose water is contaminated with PFAS. Indeed, it is likely—because of the delay and despite Ecology’s best efforts to publicize the problem and its services—that people on the West Plains are still unwittingly drinking water contaminated with high levels of PFAS.

Adding fuel to this fire of frustration is that the PFAS calamity on the West Plains is split down the middle, with Hayford Road (a necessary route to the sprawling Northern Quest casino) a highly consequential boundary. For several years, private well owners to the west of Hayford Road have been eligible for water deliveries and subsidized treatment systems from the U.S. Department of Defense if they have PFAS in their water. Yet well owners to the east of Hayford have not been eligible for DOD assistance, no matter what comes out of their wells.

Hayford Road, looking west toward the Northern Quest casino

As arbitrary as that seems, it’s not cavalier. Walk east across Hayford Road from the casino and you can peer down into a large gravel pit. Fifteen thousand years before the road was paved, ferocious Ice Age floods drilled long trenches in the basalt bedrock and then filled them in with cobbles and gravel. The gravel pit is a window into the longest trench—a 15 mile long incision, the so-called Airway Heights “paleo-channel”—that the Air Force believes is a natural barrier to PFAS from Fairchild. If there’s PFAS in groundwater east of Hayford, the Air Force insists, it’s coming from another source—namely SIA. Unless ordered otherwise, the Air Force is not responsible for paying to clean up somebody else’s PFAS.

Though the new field data appears to support the Air Force’s position, it does nothing to resolve what looks to scores of West Plains residents as an absurd circumstance—one in which well owners in the Fairchild zone west of Hayford are getting government help for their contaminated wells, but people east of Hayford, in the SIA zone, are forced to fend, and spend, for themselves.

It was just this public eyesore, and the underlying public health risks from PFAS exposures, that spurred an emergency intervention beginning in February. If it looks like multi-agency triage, that’s because it is.

As the state Department of Ecology moved last summer to force a PFAS cleanup at SIA under the state’s Model Toxics Control Act (MTCA), federal and state officials realized it may take years before the rigid MTCA process can provide a basis for direct assistance to nearby residents whose wells are contaminated. This is why EPA’s regional office for emergency response opted to step in, to work with Ecology and the Washington Department of Health to immediately conduct well testing east of Hayford Road, with Ecology working to deliver clean water to residents whose water exceeds state and federal action levels.

Three weeks ago, Ecology circulated the results from the more than 300 wells the EPA team has already sampled. More than half the wells sampled were found to have PFAS at levels exceeding state and federal drinking water standards.

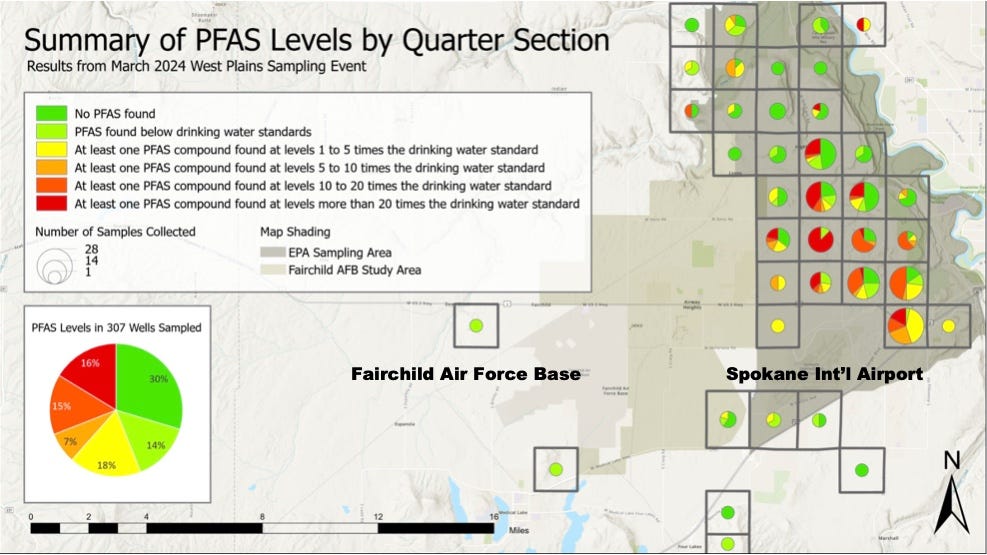

By the time the agencies convened Tuesday’s emotionally intense public meeting, EPA had prepared the graphic, above, illustrating, by quadrant, how severe the PFAS contamination is in the sampled area north (downgradient) of the Spokane airport. The dark green on the map reflects the portion of PFAS non-detects, while the dark red on the map registers PFAS measurements greater than 20 times current drinking water standards.

At least two other notable PFAS data points come from the earliest steps of the long-delayed, area-wide groundwater study led by EWU geology professor Chad Pritchard. They appear in a poster presentation delivered earlier this month by one Pritchard’s EWU students, Jerusha Hampson, which includes the detection of significant levels of PFAS in two surface streams fed by groundwater flowing northeastward from SIA. The highest measured readings (significantly above state and federal action levels) are from the stream feeding “Mystic falls” in Indian Canyon and the nearby Garden Springs brook that flows through the Finch Arboretum on its way to Latah Creek. The PFAS variant with the highest reading is PFHxS, the same variant that rendered the highest readings in blood drawn from Airway Heights residents in 2019.

The “Mystic Falls” waterfall in Indian Canyon, where high levels of PFAS have been detected.

The good news from Tuesday’s meeting is two-fold:

1) There is sufficient funding to conduct another round of well testing for up to 125 West Plains residents north of I-90 and east of Hayford Road. The application process, available now, will be open to the first 125 applicants. The new round of testing starts June 11th.

2) While Ecology is funding clean water deliveries to well owners with PFAS detections above state and federal action levels, the state is also working through the Department of Health’s Safe Drinking Water program to fund and deliver so-called “point-of-use” water treatment. According to a DOH spokesperson, the agency aims to have “countertop pitcher filters” available for well owners testing positive for PFAS (above action levels) by the end of June. Again this would be for West Plains residents in the area east of Hayford Road, basically between I-90 on the south and north to the Seven Mile bridge on the Spokane River.

As welcome as these positive developments are they hardly assuage the shock and dismay many West Plains residents are still dealing with. The Q&A session Tuesday night was long and, at times, the questions were bitter and distraught. The “point-of-use” filters will be welcome. But they won’t provide clean water to an entire household, and for garden irrigation, livestock, and pets—all of which are vulnerable to PFAS contamination that can concentrate just as it did in the bloodstreams of Airway Heights residents who were unwittingly ingesting PFAS-laden water until 2017.

One of the last people to speak Tuesday night was Jeremy Schmidt, the lead Ecology manager on the SIA cleanup project that is just getting underway this month. Currently, it is the MTCA cleanup process that has the best chance for ultimately delivering larger scale treatment systems, to be funded by the party(s) responsible for the pollution. He was empathetic, but candid about the long road ahead.

“You always start with source removal,” he said. “You go to the highest concentrations in soil and groundwater, which is normally near where it's spilled, and you remove that source and you stop it from leaving that area, whether that's excavation and disposal or other means. But the fact is with PFAS, it's going to be here for a very long time because it's moved down-gradient. It's in the soil and groundwater, it keeps becoming its own source as it enters the soil and comes back out of the soil and enters the soil, and it doesn't degrade like any other contaminant we've ever dealt with. So we're going to be dealing with PFAS for a very long time.”

—tjc

Great reporting Tim.