A Bloomsday postcard, and updated field notes from toxic water storms on the West Plains

May 5, 2024

Today marks the 47th Lilac Bloomsday Run, the annual rite of spring that put Spokane on the national map of mass participation athletic events. Congratulations to the thousands of you who ran, wheeled, and walked in sight of my window today, making strides on the rain-washed pavement.

Bloomsday runners approaching the Marne Bridge below Browne’s Addition in the rain this morning.

Link to previous installments in this series

In the beginning of the beginning

If you’re just joining this series with this installment, the West Plains are actually a plateau that rises more than 500 feet above the City of Spokane south and west of the river gorge and valley in which the state’s second-largest city unfolds. The West Plains is home to two large airports—Fairchild Air Force Base (FAFB) and Spokane’s International Airport (SIA)—both of which have a history of using large amounts of “aqueous film-forming foam” (AFFF) a flourine-based compound specifically developed and widely-marketed a half-century ago to fight fires involving aviation fuel. Until recently, AFFF was rich in PFAS—per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances—that can wreak havoc on the human endocrine system, increasing the risk for a variety of health problems, including cancer and immune system disorders.

In early 2017 the U.S. Air Force disclosed it had detected PFAS in groundwater collected near FAFB. Further investigation revealed severe contamination of municipal drinking water in nearby Airway Heights (pop. ~10,000) and more than 100 private wells.

Spokane International Airport goes rogue, and stays rogue

A year ago, documents obtained via public records requests on Spokane International Airport revealed airport officials were made aware of tests showing relatively high concentrations of PFAS in the airport’s groundwater in 2017. They chose not to share this crucial information with local and state public health officials.

Instead, it was a citizen researcher ( who obtained internal SIA memos via a public records request) who brought the PFAS contamination to the attention of state officials. In turn, the Washington state Department of Ecology notified SIA last July that it was designating SIA a “potentially liable party” under the state’s Model Toxics Control Act. Ecology then entered into an extended dialogue with SIA and its lawyers in hopes of securing a negotiated cleanup agreement. After several months of negotiations and deadline extensions, Ecology announced on March 29th that negotiations with SIA were at impasse and the agency would be moving moving forward with an enforcement order against SIA and inviting public comment.

•Ecology will be hosting a public meeting tomorrow evening (Monday, May 6th) at the HUB in Airway Heights (12703 W. 14th Avenue) beginning at 6:30 p.m. to brief the public and answer questions about the enforcement order and the proposed path forward.

EWU geologist Chad Pritchard measuring groundwater depth at a West Plains well Friday afternoon.

Initial testing points to PFAS groundwater contamination well beyond the boundaries of Spokane International Airport

As I reported in December there is disturbing evidence that SIA officials chose not to disclose evidence of the airport’s PFAS groundwater contamination problem at the same time FAFB officials were taking active steps to assist those whose drinking water was found to be contaminated with PFAS emanating from the Air Force base.

To be sure, there remain a myriad of questions and complaints for Air Force officials working on the Fairchild PFAS problem. A “listening session” convened off-base by Air Force officials the week before last (April 24th) was packed with nearly 200 people. Most of those who spoke were either frustrated by the scope and parameters of the Air Force’s response and/or by gaps in communication and followup.

To further complicate matters, at least for the Air Force, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced in early April that—after a long delay—it was setting its national “maximum contaminant level” (MCL) in drinking water at 4 parts per trillion (ppt) for most PFAS variants. This is more than ten times lower than the interim federal standard of 70 ppt that the Air Force has (up until now) been using to determine eligibility for direct assistance to those whose well water is contaminated by PFAS from Fairchild. At the “listening session” on April 24th, an Air Force official assured the audience that Fairchild would expand eligibility for its program to account for the new, stricter standard

West Plains resident Gayle Meyers addressing Air Force officials and a packed house at the “Listening Session” on April 24th

Even accounting for the criticisms directed at Air Force officials, the contrast between the federal response and the local government response, is striking—with SIA and local officials seemingly content with a wall of silence and outright defiance. The tone for SIA’s response was set last summer when a Washington, D.C. base law firm—acting on behalf of the airport—sent a blistering letter to Ecology challenging the authenticity of SIA’s own well data and trying to point the finger at the Air Force and other possible culprits.

“Whose PFAS?” the letter scolded. “Ecology jumps to the conclusion that it was the Airport’s PFAS,” and dismissing it as “an arbitrary and capricious” finding “without appropriate foundation or evidence.”

As the standoff between SIA and Ecology continued for months on end, it focused even more attention on West Plains residents with contaminated well water who’d been left to fend for themselves. This is because the Air Force concluded that although PFAS contamination from the base had made its way into private wells several miles north of the base, the Fairchild PFAS had not crossed Hayford Road, a major north-south thoroughfare three miles to the east. The problem is that several private well owners east of Hayford Road have been quietly testing, and often detecting, elevated levels of PFAS in their water. Yet, they were, and still are, ineligible for assistance from the Air Force.

The Air Force’s reasoning is two-fold.

(1) The Air Force contends that geologic investigations reveal a groundwater divide that serves as a natural barrier preventing Fairchild PFAS from reaching wells east of Hayford Road.

(2) The Air Force is confident there is a second major source of PFAS contamination, and it’s not a Fairchild. As Mark Loucks—the Air Force Environmental Restoration Branch Chief who’s become the principal spokesperson for Fairchild’s PFAS response—explained in an email sent to an alarmed West Plains resident last November, the Air Force has concluded that SIA has been a “user of AFFF” for decades.

“There are at least two known source areas [at SIA] that have likely impacted groundwater with PFAS constituents,” Loucks wrote. But because the Air Force is not authorized to spend federal funds on pollution attributable to other sources, Loucks conveyed his condolences but advised the well owner to appeal to local, state and federal environmental/public health agencies for assistance.

In short, those appeals worked. Recognizing the plight of at least dozens of private well owners beyond the reach of the Air Force’s assistance, the federal Environmental Protection Agency joined the state’s Department of Ecology in announcing a plan that would better define the scope of the PFAS contamination problem east of Hayford Road and also provide direct assistance to area well-owners whose water tests positive for PFAS.

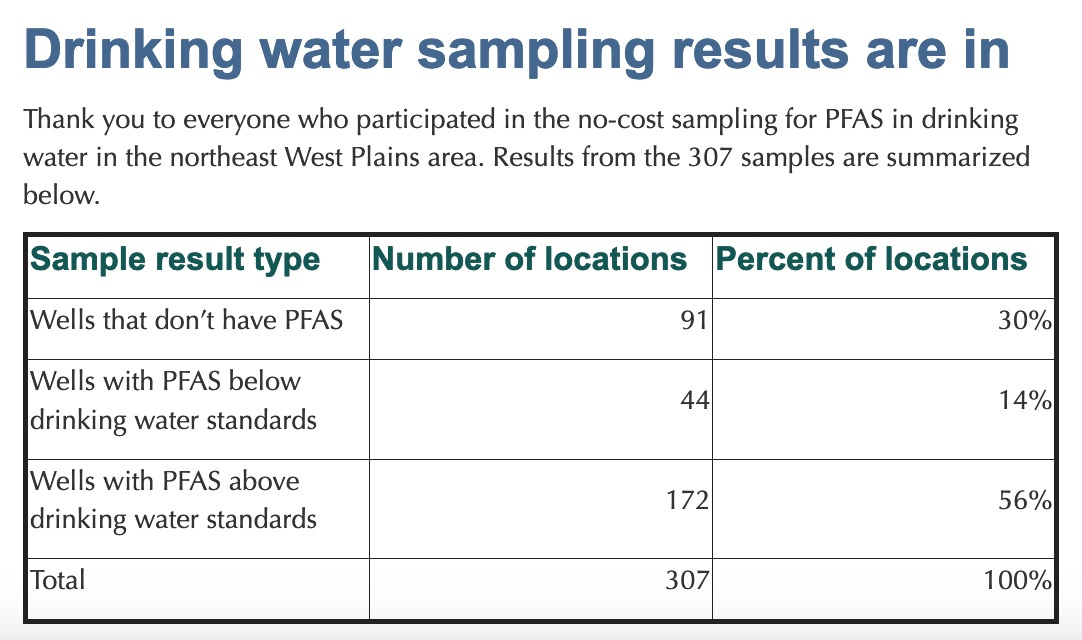

Source: Washington Department of Ecology, 5/1/24

Last week, Ecology distributed the results (above table) of the new sampling project east of Hayford Road. Of the 307 locations tested, more than half (172) returned results exceeding drinking water standards. Suffice to say the findings are an ominous indication, corroborating earlier sampling (funded out of pocket by well owners) indicating PFAS contamination from SIA has migrated well beyond the airport’s boundaries.

EWU geologist Chad Pritchard is the lead investigator in a Department of Ecology-funded project to better track and model PFAS contaminated groundwater movement on the West Plains. When I interviewed him late last week he said surface water sampling of Indian Canyon Creek and Garden Springs Creek (small streams clearly fed by groundwater flowing northeastward from SIA) has also detected elevated levels of PFAS.

Commissioner and SIA board member Al French at the April 11th public meeting

Commissioner Al French locates a culprit, and a magical pipe

For the past year, Spokane International Airport board members and executives have avoided public events focusing on the West Plains PFAS controversy. Their absence has not gone unnoticed. Among several other voids, the question of why SIA failed to notify public health officials (let alone its neighbors) when it detected PFAS contamination in SIA groundwater remains unanswered.

In the past month, however, long-time SIA board member and Spokane County Commissioner Al French has appeared at a couple public meetings where the subject came up. The first was on April 11th when he appeared alongside County Sheriff John Nowels at a public meeting largely devoted to West Plains’ neighborhood concerns about transient crime and drug use. Before he left the meeting for another scheduled engagement, French was quizzed by a neighborhood activist about why SIA had failed to even apply for a state grant that could have provided a hefty amount of the funding needed for SIA to implement the mandated PFAS cleanup. To put it mildly, French opened a can of worms. He put the blame on the Federal Aviation Administration.

To qualify for the state grant, SIA would have had to fund between 25% and 50% of the cleanup costs, with the state covering the remainder. But even that, French indicated, would somehow jeopardize the airport’s federal authorization and federal grant money from FAA.

“One of the requirements from the FAA,” French said, is that we cannot diverge [sic] revenue from the airport for any use other than aeronautical use. So in the letter that Ecology has presented, it requires that the airport divert those funds, which then gets us into conflict with the FAA.”

Without FAA approving SIA’s expenditure of funds for cleanup, French continued, the airport would be risking FAA’s wrath.

“And so that’s the trigger,” French said, adding, “if we just say we're in it [funding cleanup] and the FAA says ‘wait a minute you’ve jeopardized your grant funding, we want all that money back, and oh by the way, you're no longer authorized to operate as a commercial airport.’ That's a big issue.”

As he departed the April 11th meeting, French committed to holding a second public meeting exclusively on the PFAS issue. That meeting took place, at the same venue, on April 23rd. This time, French brought with him a short powerpoint presentation of a new proposal he said he’d already begun sharing with local, state, tribal and federal officials. It is the solution he imagines will solve the West Plains PFAS problem by making clean, Spokane River water available to all groundwater users, including individual well owners, whose well water is contaminated with PFAS contamination.

Given the competing demands for water from the Spokane River (and groundwater from the Spokane/Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer which is essential for the river’s flow requirements) French’s proposal is ambitious, to put it mildly.

It would also be very expensive. It would require countless miles of pipes, many of which would have to be laid not in gravel but in the tough, basaltic bedrock of the West Plains. The first essential “pipe”—to use French’s word for it—is a virtual pipe. In French’s plan you have to imagine the “pipe” as the current of the Spokane River, carrying 8 million gallons a day. This is the daily discharge of treated wastewater to the river from Spokane County’s wastewater treatment plant in the Spokane valley. To assuage likely protests, French’s proposal treats the wastewater as an added contribution to the river’s flow—a contribution to the river that the county should be allowed to collect downstream and pump uphill to solve the West Plains’ problem. But the math is contorted: Essentially all of the county’s treated wastewater begins as clean water pumped from an aquifer that is a vital, natural source of water for the river. In other words, the county’s wastewater plant simply treats water in the overall hydrologic system, it doesn’t actually add water to it.

French delivered the plan with gusto, but drew a wave of laughter from the audience when he said: “My time frame is to have this done by next summer for all of you.”

And who would pay for this? Federal taxpayers.

As best I can tell, SIA’s position is that even if there is a big problem with PFAS in its groundwater (and the available evidence suggests there is) SIA should not be deemed the responsible party. Instead, SIA points a finger toward the FAA—for requiring that the airport purchase and use the PFAS-laden foam in the first place.

At the meeting on April 23rd, French repeated what he’d said at the earlier gathering—that the FAA mandated use of the PFAS-laden foam as a condition of the airport’s federal certification.

“So if they mandate it,” French said, “they ought to pay for it.”

“So I can tell you,” he added, “that part of the effort is to get FAA to cough up the money.”

In the meantime, FAA appears to be disputing French’s contention that the agency will threaten SIA’s authorization or its federal grant funding if it enters into a cleanup agreement with the state. In late April, the Spokesman-Review reported on a letter from an FAA program manager stating that FAA requirements don’t preclude airports from allocating funds to resolve environmental litigation.

“In general,” the letter reported, “there is no bar on an airport using its own revenue to discharge it’s legal liabilities or to settle cases even where liability has yet to be adjudged.”

I asked the FAA press office for a copy of the letter. My request was denied, and I was instructed to file a Freedom of Information Act request.

—tjc

"My time frame is to have this done by next summer for all of you.”

Everyone is talking out the side of their mouth.

Grateful for Tim's continued diligent and thorough reporting.