Tuesday's postcard, and the days between the nightmares

August 8, 2023

Late afternoon moonrise in the northern Palouse, near St. John, WA

Four days in August

Eighteen days ago a friend invited me to a theater to see Oppenheimer, the movie, on its opening day. I wouldn’t have gone by myself. I know of the blinding light and Oppenheimer’s famous quote from the Baghavad Gita—‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds’—to describe his reaction.

To write that it’s an unsettling subject puts it too mildly. I wrestle with nuclear fatigue and the fear incumbent in nuclear weapons. It’s a subject I investigated and wrote about for several years, working to and through the grim awareness that we’re all part of this story, inasmuch as the existence of nuclear weapons (more than 10,000 worldwide) threatens all of us with the specter of annihilation.

Oppenheimer, the film, takes several paths to the existential paradox: that we humans are more clever than wise. We proved we’re smart enough to unlock the mind-boggling energy of the atom. But step out of the laboratory and we’re still in the fever swamp of human egos and ordinary cruelties of twisted power plays. As Albert Einstein put it in 1946: “The unleashed power of the atom has changed everything save our modes of thinking, and we thus drift toward unparalleled catastrophe.”

Oppenheimer showcases this, and how its tragic, namesake lead-character was haunted by his role in creating the bomb. It troubled him to the point where he told President Truman he felt he had blood on his hands. In the movie Truman hands him a handkerchief to wipe his hands. He dismissed Oppenheimer as “a cry-baby,” and refused to meet with him again.

It is a quirk of fate that I was born at Hanford—the site of the massive, secret factories that produced the plutonium for the “Trinity” detonation that erupts at the climax of Oppenheimer. My mother’s family, the Hartmans, are from nearby Pasco. Pasco is only 15 miles from Hanford but seemingly a world away in its guise as a large farm town situated near the confluence of the Snake and Columbia rivers. The mascot at Pasco High is a bulldog. At Richland High, near the Hanford gates, the mascot is a mushroom cloud. My mother was fond of calling Pasco “God’s Country.” Plutonium is named after the Greek god of the underworld.

I got used to traveling between these two places when I was a young journalist. After I applied for a reporting job at the Tri-City Herald in nearby Kennewick, I was interviewed by Glenn C. Lee, the paper’s publisher. Lee was famous both for his temper and his unapologetic support for all things nuclear, all things Hanford. Our meeting didn’t go so well. He didn’t like me. I didn’t like him. He abruptly ended our interview when he learned I didn’t own a car; that I’d borrowed my sister’s Chevy Impala to get to the appointment. Before I could even leave his office he began to chastise the associate editor who’d recruited me. Some days are like that.

The irony is that Lee’s promotion of Hanford compromised the newspaper’s coverage and, five years later, as a freelance writer, I was finding remarkable stories in the newspaper’s blind spot. This included a story about an illegal plan to modify Hanford’s PUREX—the world’s largest plutonium processing plant—so that it could suck plutonium for nuclear weapons from civilian reactor fuel rods. I sold the story to the Seattle Weekly.

One of my sources at Hanford was Jim Stoffels, a veteran physicist whom I first met in the basement of the Pasco church where my great-grandfather was once pastor. Jim is a co-founder of a Tri-Cities peace group—World Citizens for Peace—several of whose members worked at Hanford.

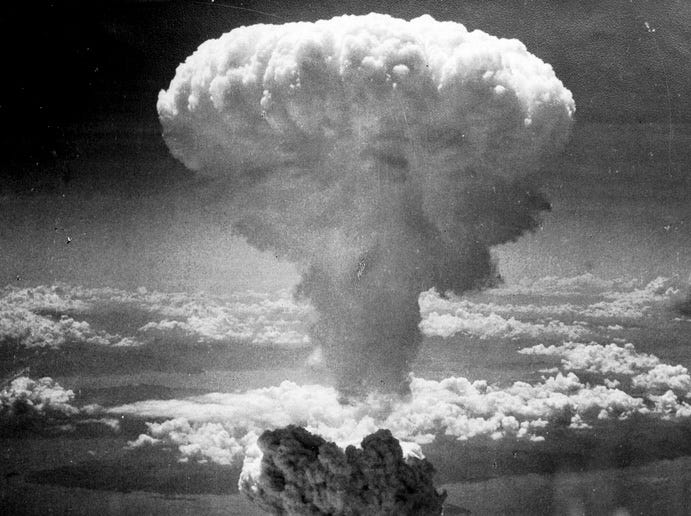

Starting in the early 1970s there had been a lull in plutonium processing at Hanford and a shift toward civilian nuclear energy research. That changed abruptly in the early 1980s as tension between the U.S. and U.S.S.R ratcheted up and, with it, plans to refurbish and restart PUREX and its support facilities. Jim and his fellow members of World Citizens for Peace protested against the new plutonium production campaign. Among other events, the group organized solemn public vigils in early August, a stone’s throw from Hanford’s headquarters, to commemorate the tragedies of the Hiroshima bombing on August 6, 1945, and the Nagasaki bombing on August 9th of the same year. (The estimates of the combined death tolls from Hiroshima and Nagasaki range from 110,000 to upwards of 200,000.)

I think of August 7th and 8th as the days between the nightmares. I’ve seen the photos; I’ve read John Hersey’s classic 1946 account of the aftermath of the Hiroshima bomb. I’ve made myself familiar with the long-term health studies of the hibakusha—the survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings who were exposed to high levels of neutron radiation. I know enough to scare most people. I know more than enough to scare myself.

The mushroom cloud crown of the Nagasaki explosion, fueled by Hanford plutonium, August 9, 1945

Plutonium is nasty, frightening stuff. But it is our custody of it that is far more perilous. It didn’t change us enough, and not nearly as much as Einstein, Oppenheimer, Andre Sakharov, Leo Szilard and dozens of other prominent scientists hoped it would. There’s a foreshadowing of that in Oppenheimer in a scene where “Oppie”—a new hero in the aftermath of the Trinity test—tries to give advice to the military men who arrive at Los Alamos to take away the carefully prepared, Hanford-produced plutonium core for the Nagasaki bomb. It’s a curt ‘thanks but no thanks’ moment. “We’ll take it from here,” the lead officer tells Oppenheimer.

Plutonium requires us to be perfect custodians, and the most basic and least reassuring fact is we’re imperfect. The bulk of my Hanford reporting—including a cover story for The Oregonian’s Sunday Magazine—was in the early 1980s, when Ronald Reagan’s new national security team was seriously contemplating and developing plans to “win” nuclear wars with the-then Soviet Union. The chilling story is told in a remarkable 1982 book by journalist Robert Scheer, entitled With Enough Shovels: Reagan, Bush and Nuclear War. You can listen to Scheer’s account of it in this 1982 radio interview with the legendary Studs Terkel.

Even removed from purposeful, nuclear saber-rattling, the annals of the nuclear age record several instances where, by accident or mistake, both the U.S. and former Soviet Union have armed intercontinental missiles and hastily prepared to launch them. The idea for winning a nuclear war is to quickly destroy most of your enemy’s nuclear weapons with a devastating first-strike. The fear of a surprise nuclear attack forces both adversaries to make quick decisions that only heighten the chances of an accidental catastrophe.

The high water mark of Oppenheimer is the period between the successful Trinity test on July 16th and the bombing of Hiroshima three weeks later. The Hiroshima bombing is greeted with a patriotic pep rally at Los Alamos, from where Oppenheimer coordinated the undeniably brilliant scientific and technical feats. In the film, the pyrrhic pride of the bomb’s creators warps in the film-maker’s lens: the foot-stomping celebration bends into an imaginary horror scene, the cheers turning to vomiting in reaction to the charred and irradiated human carnage, half a world away.

Within minutes of the Hiroshima bombing, the White House put out a press release, reporting not just on the bomb, but the role of Los Alamos, Hanford, and Oak Ridge, TN, in the development of the weapons and their fissile cores. This is how the Pasco Herald—the predecessor to the Tri-City Herald—reported it on its front page on August 6, 1945.

“Almost unbelievable. The news so closely guarded throughout two and a half years was out. Atomic bombs. ... And in the hearts of men and women of Pasco Monday was pride coupled with the intense interest they had always felt for the big war project that had grown up practically across the back fence from them since the spring of 1943.”

Front page of the Richland, WA newspaper, August 6, 1945

My mother was twelve that day, 78 years ago. Before she passed, and while she still had her memory, she told me she remembered her older brother, my uncle Terry, running into the house exclaiming “it’s atomic bombs!,” by which Terry meant that’s what all the new buildings and tens of thousands of newly arrived workers had been up to in the desert northwest of Richland.

The big mystery of Hanford was solved. It was replaced by the grim question of whether we can somehow survive the ferocity of what we created, and used, twice.

The bomb is not even 80 years old. Given that civilization is roughly 10,000 years old, 80 years offers only a crumb of confidence that we can avoid self-annihilation. We came perilously close to nuclear war during the so-called Cuban Missile Crisis in October of 1962. There’s evidence that the U.S. was considering using nuclear weapons against North Vietnam during the early years of the Nixon Administration. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has only heightened tensions between the nuclear superpowers, not just the U.S. and Russia, but the U.S. and China. It is not the least bit crazy to imagine we’re living on borrowed time.

Desert sunset east of Pasco

I can’t help but think about that every August, during these four days— between the nuclear nightmares of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In my prayers, I don’t want the world of the Pascos—the white picket fences, the flowering lilacs, the humming from my grandmother’s kitchen, the poplar leaves stirring in the dry winds off the Horse Heaven Hills—to live cheek-by-jowl with the world of the plutonium sucking PUREX plants. Like any other father, or mother, I wake in the middle of the night and think of my children, and try as hard as I can to keep my hopes for them ahead of my fears.

—tjc

Thanks so much Bruce!