Autumn at Steamboat Rock, in Upper Grand Coulee

A bold geologist’s hundred year-old bootprints on our region

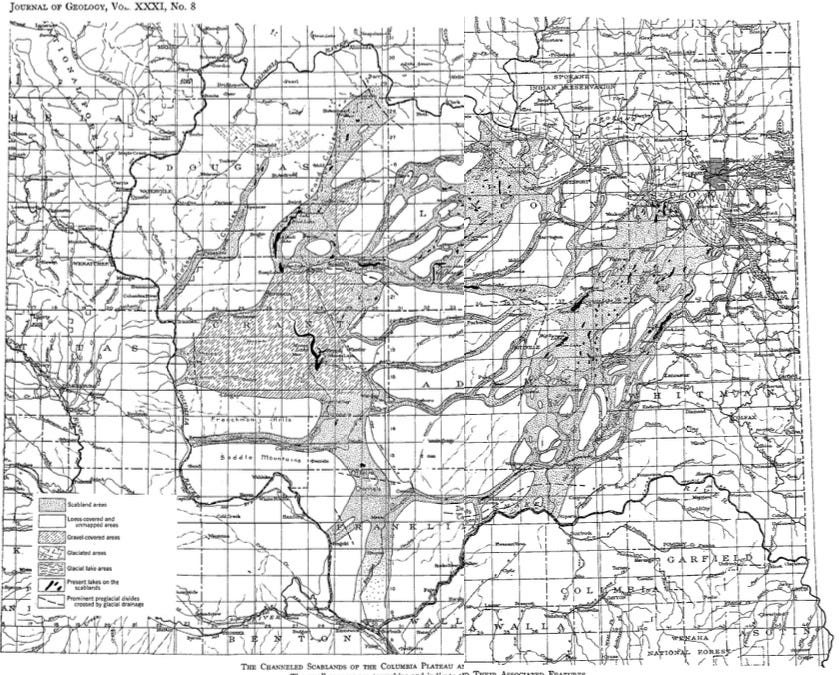

This year is the hundredth anniversary of one of the great papers of American earth science: J Harlen Bretz’s 1923 article, Channeled Scablands of the Columbia Plateau, published in the Journal of Geology. It was the result of two summers worth of field work that Bretz and his graduate students from the University of Chicago undertook, working largely out of Spokane. The paper included a vintage, meticulous map of the scablands’ drainages to the south and west of Spokane.

At the time, and still for decades to come, there was intense debate over how the scablands were created. The majority of Bretz’s peers were steeped in “uniformitarianism”—the view that topography evolved by standard erosional processes over millennia. But Bretz saw catastrophe on the terrain, an overwhelming flood or floods that he first called the “Spokane flood” because of the compelling evidence that the Spokane valley was a nozzle of sorts for the rampaging flood waters moving west and south into three major scabland tracts.

Map of the Channeled Scablands that accompanied Bretz’s 1923 paper. (Courtesy Special Collections, University of Chicago Library) Spokane is located in the upper right hand corner

Bretz’s life and work are documented in several books and in the 2005 PBS NOVA documentary Mystery of the Megaflood. His story has several facets and a familiar theme that coincides with what, on a broader scale, was the most radical geologic epiphany in the past century. This would be the (now) fully embraced theory of plate tectonics—that the world beneath our feet moves, at about the pace a fingernail grows, opening oceans and moving continents on crustal plates that ride atop the heat-stoking mantle.

To continue reading please subscribe to The Daily Rhubarb