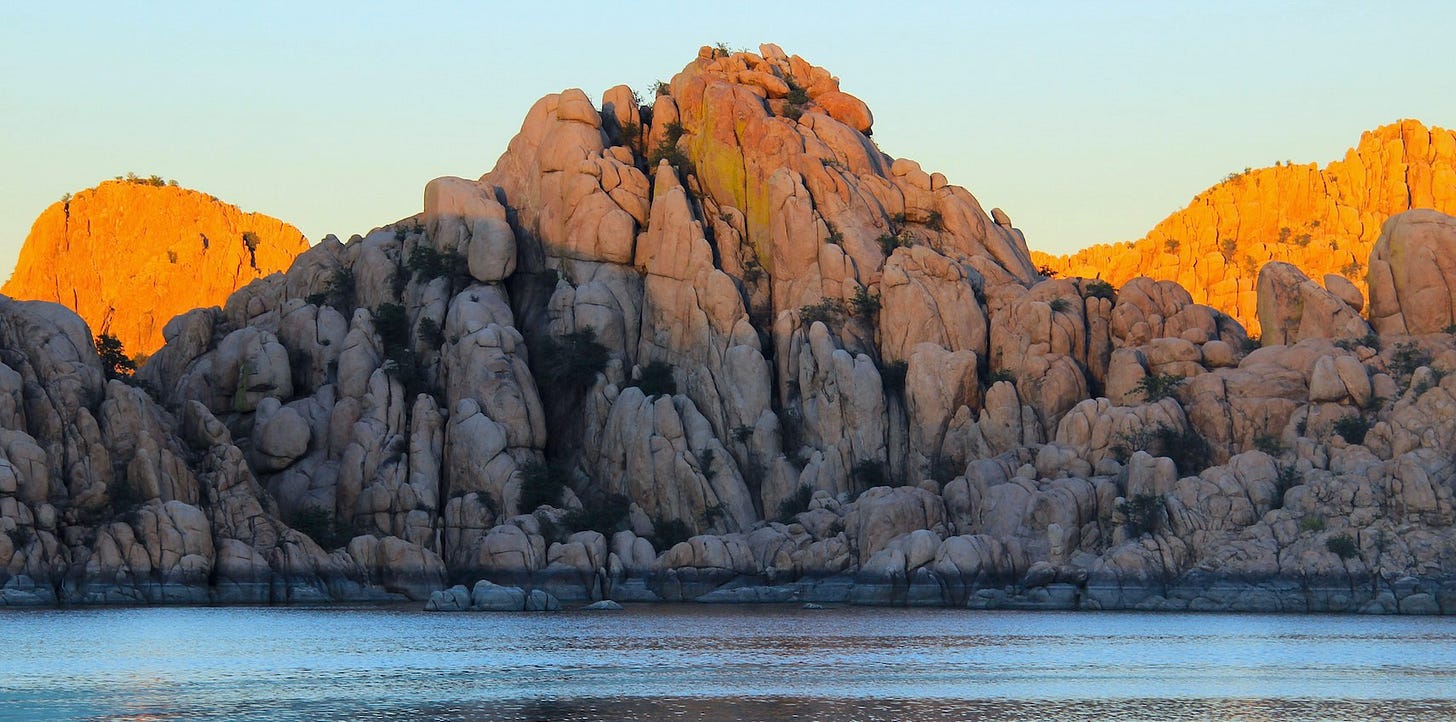

Sunset at the 1.4 billion year old Granite Dells near Prescott, Arizona

An intervention of our better angels

There are some events most of us didn’t learn in school because they don’t comfortably fit with our notion of who we are, and how we got here.

One of those events took place nearly a century ago, on a sweltering September day in Washington, D.C. It was an unexpectedly large march, right through the heart of the nation’s capital. Spokane’s most decorated writer—Tim Egan—describes it in his most recent (2023) book, A Fever in the Heartland, The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them.

The parade was an intimidating show of force—some 50,000 marchers in white sheets led by an “Imperial Wizard” from Dallas by the name of Hiram Evans. They were cheered on by a crowd estimated at a quarter million.

The purpose was to signal Americans—and especially America’s leaders—that the Klan was a rising, inexorable force: a white, Christian nationalist movement out to purge society of Jews, Catholics, immigrants, and African Americans. In that signal, they succeeded, at least for a while. The front page headline in the next day’s New York Times read: “Sight Astonishes Capital,” and the Washington Post described it as “one of the greatest demonstrations this city has ever known.” It was so daunting that President Calvin Coolidge—no doubt aware of the Klan’s rising influence—left the capital and avoided saying anything about it.

A half century earlier, President Ulysses S. Grant had vigorously prosecuted the Klan in the aftermath of the Civil War. But now the Klan was back, and although the Klan had risen from the South, Egan reports that 90 percent of the marchers that day in 1925 were actually from northern states. It was a rapidly growing movement, including large contingents in Colorado, Oregon and Washington.

I’ve been thinking of Egan’s book (a gift from a dear friend and loyal reader of The Daily Rhubarb) quite a bit this week.

For two reasons.

As with Nikole Hannah Jones’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “1619 Project”—“Fever” covers a history that most of us are largely oblivious to, at least in terms of its blood-chilling specificity—the anti-matter of evil (slavery, lynching, etc.) that haunts the actual story of the United States. The one thing Florida Governor Ron DeSantis (who, you may have read, has banned the book from the state’s public school curricula) and I can agree upon is that the 1619 Project can make readers “uncomfortable.” Both “Fever” and the “1619 Project” confront us with atrocities that can’t be reconciled with our ideals about justice and dignity, and not to mention those precious tenets of religion that direct us toward heaven with brotherly love.

In Egan’s “Fever” there’s also an unmistakable, historic echo into the present, to Donald Trump and Trumpism, to a former president, now a recently convicted felon and sexual predator who—nevertheless—was just anointed by the Republican Party to be the GOP nominee for president in 2024.

A century ago, the woman who “stopped them”—Madge Oberholtzer— didn’t survive. She was kidnapped and brutally raped by David “Steve” Stephenson, a Klan “Grand Dragon” based in Indianapolis who, at the time of the crime, was widely recognized as the most powerful person in the state of Indiana, in large part because he was prolific at blackmail and bribery. Moreover, Stephenson was the man who led the KKK’s upheaval in the Midwest, one he hoped to ride to the nation’s presidency.

Aside from being a KKK Grand Dragon,“Steve” was a violent sexual predator and a raging alcoholic—both ironies given the KKK’s expressed devotion to chastity and temperance. No matter. “Steve” began to believe—like Trump—that he was invincible. At one point during his kidnapping and assault of Madge Oberholtzer he told her resistance was futile: “I am the law in Indiana.”

He also told her he could never be indicted. That was close to true. But not quite.

Madge Oberholtzer poisoned herself with mercury after she was raped by Stephenson, but she lived long enough to give a detailed sworn statement on her death bed. (The medical testimony is that she may have survived the poisoning, but not the raging infections from the numerous bite wounds inflicted on her body as the Grand Dragon was raping her.) Her deathbed affidavit and corroborating testimony from witnesses to the kidnapping got Stephenson convicted by an all-white, all-male jury. The testimony and verdict in the high-profile case shamed not just the Klan but those who’d tolerated and supported Stephenson and the Klan’s virtual takeover of Indiana state government and its burgeoning influence throughout the upper Midwest. The trial captivated the nation. It also occurred in the same time frame as other trials and convictions of Klan leaders, including the leader of the KKK in La Grande, Oregon, who was convicted after raping his assistant and then killing her during a botched abortion.

To continue reading, please subscribe to The Daily Rhubarb at the link below