Tuesday's postcard, a stardust postscript, and some Valentines

February 14, 2023

Hoarfrost on wild rosehips

Because two of the first three topics in the Provenance series involve astronomy and astrophysics it’s a good day to give some love to women in astronomy. For most of its history the science of the stars has been the province of men, with women relegated to support roles away from the telescopes.

That has begun to change, with time, but it’s still important to listen to contemporary female astronomers like Emily Levesque speak bravely and candidly about their experiences in a highly competitive and traditionally male dominated profession. I’ll attach a video of one of Ms. Levesque’s lectures—The Weirdest Stars in the Universe— below, because she’s a dynamic presenter and it’s a great topic besides.

From the past, we owe much to—

Henrietta Swan Leavitt (1868-1921), a Radcliffe College graduate who worked most of her career at the Harvard Observatory. At Harvard she was, quite literally, a human computer, and assigned the formidable task of analyzing thousands of glass photographic plates in order to catalogue stars of variable brightness. When she published her work in 1908 she had identified 1,777 “Cepheid variable” stars. Most importantly she was the first to notice that this class of pulsating stars had a distinct rhythm to it, with the brighter stars having the longest pulses. This, in turn, became the key to forming accurate measurements across the visible universe, and work that the famous astronomer Edwin Hubble was able to use to discern and propose (correctly) that Andromeda was a galaxy beyond our Milky Way.

Vera Rubin (1928-2016), a Vassar College graduate is now celebrated mostly for her observations on the rotation of galaxies, in which she demonstrated that the gravitational effects on the speed of stars circling the center of galactic spirals was inconsistent with the observable mass of the galaxy. In short, her remarkable measurements confirmed the existence of what is now known as “dark matter,” an as yet unidentified and invisible substance that outweighs visible matter in the observable universe by roughly 6 to 1. It was a stunning discovery. Among other honors, a new sophisticated observatory in Chile (funded privately and through the National Science Foundation) has been named in her honor as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and is scheduled to being operations later this year.

Bouquets of appreciation also go to two, contemporary women astronomers whose TED Talks were helpful in studying for The Geology of Us piece: Karen Kwitter, the Ebeneezer Fitch Professor of Astronomy at Williams College, and Northern Ireland astrophysicist Jocelyn Bell Burnell who is perhaps best known for NOT receiving a Nobel Prize for her discovery of pulsars (highly magnetized neutron stars) in 1967. The award went, instead, to her male co-author on the paper reporting her discovery. As you’ll see from the opening scene of her TED Talk—where she uses “tomahto” ketchup to fake a bloody wound—she still has a terrific sense of humor.

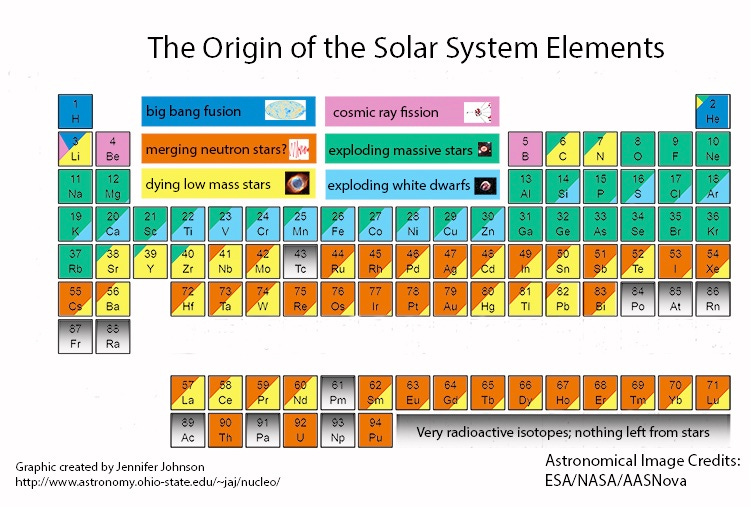

Finally, a bouquet as well for Jennifer Johnson of Ohio State University’s Astronomy department for compiling what I think is the best Periodic Table of the Elements I’ve come across. It is color-coded to indicate what types of exploding or dying stars are the sources for each of the heavier elements. A valuable resource.

—tjc