Larrabee State Park south of Bellingham, WA

Friday Four-minute Fiction

“When Murray met Helen,” Chapter 9

Reconcile

Helen left through Murray’s kitchen door and, within the hour, returned with fruit. Along with the pineapple she unpacked fresh strawberries, raspberries, a variety of cubed melon, and dark cherries.

“What, no peaches?” he asked, with a tone of mock entitlement.

“Not this time a year,” she said. “Not unless you want to eat them from a can. We’re just damn lucky I scored the cherries.”

Murray was sitting up by then in his burgundy barcalounger, wrapped in a purple and blue Northwestern blanket, like an old guy tucked in a woolen burrito.

“Oh, I’m lucky,” he said wistfully. “I’m so damn lucky, lucky just to be here.”

She had a strong urge to scold him just then, about going up on his roof, without help, to adjust his silly antenna. Instead she just fixed him with a piercing gaze and said, “uh, hmm,” tersely, nodding her head in just such a way that she knew he would get the message.

“What?” he asked.

“You know damn what,” she spat back, without raising her voice.

He looked back at her and then, his eyes drifting, shook his head, gently and remorsefully, for what he’d put her through.

“Those strawberries are just perfect,” he said, changing the subject. “They had to come from your garden.”

“Actually, I got them from yours,” she said, coaxing a smile.

“Helen,” he said, “I just have to say this once…

“You don’t like the dark cherries?” she jested.

“No,” he said, and then drew a deep breath.

“Listen. Calvin Coolidge was President when I was born. We only had radio. There were no satellites, no jet planes, and if anyone had even thought of what a computer would be, they were keeping it to themselves. Everybody was afraid of polio and my dad came this close to becoming a Communist. I was born into a world you wouldn’t recognize and I did things you cannot, you could not, you will not possibly imagine, as you sit there, looking at me in my dissipating body and my ridiculous, old man iguana skin, and wondering, as you surely should, just what the hell I think about most of the time.”

She had laughed, gently, at “old man iguana skin.”

“I remember so much,” he continued. “But there’s so many things I can’t do well any more, including explaining why I would do a crazy-assed thing like go up on my roof and fall off. Do you understand?”

She looked at him, smiled gently, rolled her eyes, then stroked her chin.

“Oh, sure, Murray,” she replied. “When you put it that way, it actually makes a lot of sense. How could it be otherwise.”

With that she tossed and bounced a cherry off the side of his head.

“Ow.”

Then they started chuckling, softly at first, and then heaving until they both began to sputter. Neither could stop for several minutes and Helen wound up drying her eyes on her sleeve.

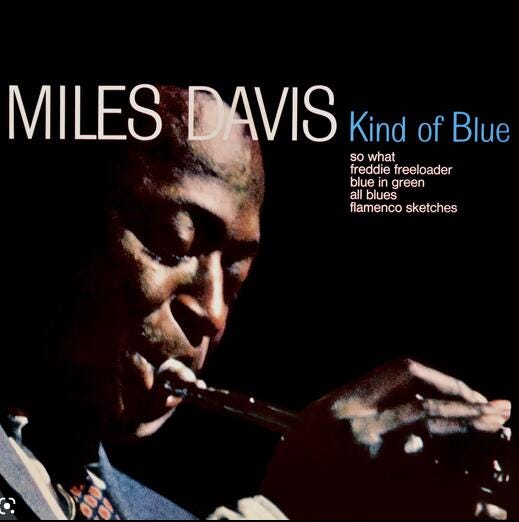

When she recovered and got up to leave, Murray asked if she would put Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue on the turntable across the room, and fetch him his book.

Despite the blow to his head he was still moving backward in time, more deeply into the Durants’ Story of Civilization, Volume 9, walking in Voltaire’s footsteps, trying to reconcile reason and religion.