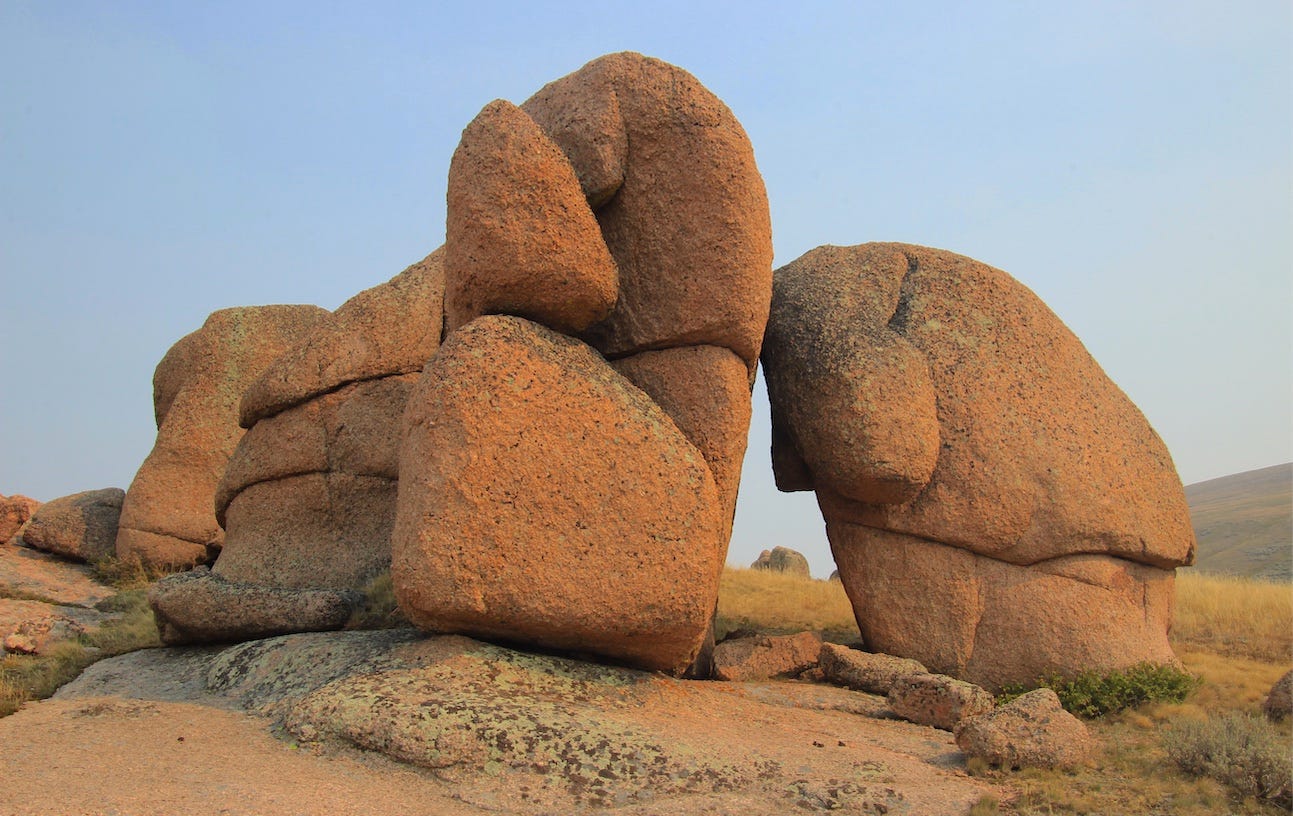

Wind-sculpted Precambrian granite atop the Bighorn Mountains in northern Wyoming

The hot truths about climate change

I had planned another topic for today’s Daily Rhubarb. But “cocaine-gate” has come upon us. Like a daily dog treat of human news—it’s vital that we all bark and jump because a “small amount” of the white substance “was found on the ground floor of the West Wing near where visitors taking tours are instructed to leave their cellphones.”

Who knows? Perhaps a thin white trail leads to the Lincoln bedroom, or worse.

I jest, of course.

By far the most important news this week is that for two successive days, July 3rd and July 4th, the planet’s average temperature was the highest humans have ever measured, nearly 63 F.

The global fever is clearly connected to another metric—carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. It was troubling news a decade ago when carbon dioxide was measured at 400 parts per million, the highest level recorded in human history. At the turn of the century, 2000, the concentration was just under 370 parts per million. Today it is rapidly approaching 420 parts per million.

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

It’s important news because we’re suffering as a result, not just we humans but the global ecology and thousands of species of plants and animals.

I’ve used the word “news” but really it’s not new. We’ve seen this coming for quite some time. By now we know quite a bit about the physical science as well as the stupefying human indifference to it.

As you can probably discern from the first 100 or so installments of The Daily Rhubarb, one of my focus areas is science. But I haven’t written anything about climate change this year, and not much in the past nine years.

Why?

In short, because I didn’t have anything meaningful to add to what I’d offered a decade ago in a 4,500+ word piece, Tipping Points.

The piece is chock full of science. It also goes into depth about a devastating 2012 Frontlines documentary, “Climate of Doubt,” that vividly exposed a campaign funded by fossil fuel interests to undermine the science connecting fossil fuels to CO2 levels and the scientists’ warnings about the ramifications of a rapidly warming planet.

If you wonder why we can know so much about global warming and how human activity causes it—and still do next to nothing about it—the Frontlines documentary answered that question. The fossil fuel industry’s goal was to confuse people about who and what to believe. It was as cynical as it was successful, and the Frontlines exposé includes footage of its leaders chortling and bragging about how easy it was to manipulate public opinion and defeat all the meaningful, national legislative initiatives on the table at the time.

The effectiveness of the oil industry-funded disinformation efforts are still with us. It’s visible in the remarkable gulf between public opinion and scientific opinion regarding whether climate change is real, and whether human activities are a principal cause. The most consistent major poll on this question is from Gallup, which does an annual survey on public opinion related to climate change. The percentage of Americans who agree on the connection between human activity and a warming climate has remained steady at just over 60% since 2016.

Yet, there is nearly 100% consensus among scientists publishing in peer reviewed journals that climate change is real, and that humans are the major cause.

That warp is even deeper in our politics. A Pew poll in 2021 found that only 17% of Republicans agree with the scientists that human activity is a major contributor to climate change.

A good portion of my Tipping Points piece was devoted to what happened to my men’s discussion group in 2014 when one of its founders held court—airing talking points from fossil fuel apologists. It didn’t go so well, and I’ll admit to being the first and loudest to disrupt his presentation. It nearly ended in a brawl, with the restaurant owner perspiring and on the verge of throwing us out. It was awful, about as bad as a discussion group can get without bloodshed or arrests.

As the melee subsided I returned to my seat. One of the group’s other staunch conservatives sat across from me and asked:

“Do you support sustainable communities?”

I didn’t realize until that moment that “sustainable communities” was code for socialism, or worse.

I laughed in amazement at the question.

“Are there any other kind?” I replied.

He responded by placing both hands on the table and shaking his head. “Then I’m done with you,” he said, and promptly got up and left.

What I learned later is he was most concerned about his investment portfolio (a significant portion of which was in or tied to fossil fuels). He was concerned about whether it would be adequate to support his mother’s health care needs, and whether he would be able to pass on what remained to his children.

Two things. I truly empathize with his concern. Mothers are important and so is an inheritance. But they shouldn’t come at the expense of economic justice and our environment. There are millions of Americans like me who detest that corporate profits and stock values rely on what economists call “externalized costs”—damage done to the public square as a result of pollution or other corporate vice that falls upon taxpayers to clean up and foot the bill.

When it comes to climate change, the planet is the public square, and, as Greta Thunberg teaches with great resolve and courage, it’s really important not to shut up about what’s happening—right in our face, right before our eyes.

One of the pieces I read, yesterday, that I’d recommend is an article by Olivia Paschal, who grew up in Arkansas. Her piece, for The Atlantic is entitled “Summer in the South is Becoming Unbearable.” Here’s one of the more gripping paragraphs:

Laborers are especially vulnerable. The South’s agricultural economy, propped up for centuries by enslaved Black workers, now relies on farmworkers—and because of lobbying by segregationist southern lawmakers, those workers are exempt from the National Labor Relations Act. No federal regulations protect farmworkers—who are mostly noncitizen immigrants from Latin America, commonly live under the poverty line, and have few legal rights—from extreme heat. Farmworkers die from heat-related injuries at 20 times the rate of other laborers. A 2020 study estimated that the number of days farmworkers labor in extreme heat will double by mid-century. The state of Texas just rescinded rules requiring water breaks for construction workers, exposing them to greater risk of dehydration and heat stroke.

A generation ago, the thought of a rapidly warming planet that would make parts of the globe virtually uninhabitable was beyond most of our experience, let alone our imagination. But it’s here now.

—tjc