I remember a moment, just after the 2016 election, when I was sitting on a beige couch in the house of one of my mother’s friends during a compulsory holiday gathering. It was a moment prior to the polarization we experience now, such a driving force—not just in our politics, but in our culture, media, and proximate relationships. This was when the novelty of Trump as a political figure still felt new, still felt temporary; a bug our country was working out of its system. At least, that was my understanding of the moment, based on the conjecture and hopefully assertive assessments of those around me.

And yet suddenly, at this Christmas party, I found myself in a conversation with a woman who had voted for him, and I felt my physical form slowly contract as she spoke with pride about her decision.

I’m a survivor of some stuff, like probably every woman you know (and plenty of men, and a breathless amount of trans people). So, like many of these people you probably know, I have spent a lot of time unable to admit the truth to myself. But at this moment in 2016, I was reluctantly coming to grips with the reality that trying to will the trauma away wasn’t doing much for me. After years of tamping it down, I was working with a therapist to learn how to talk about it in my own internal monologue. I was barely at a point where I could say it to other people.

It was then, in my era of nascent reluctant victim-hood, that a woman was vocalizing to me how unabashedly proud she was to be on the election’s winning team. The Access Hollywood tape had been released and widely viewed a month before, igniting outrage and a torrent of additional, new allegations. And yet, nearly half of our country’s fellow white ladies had also decided that this wasn’t a deal breaker for them. They voted for him anyway.

I remember saying to this woman, “I’ve been sexually assaulted,” and her face going to stone. I remember telling her that I couldn’t vote for someone who had been accused of violence by so many. Even now, I’m not sure that my conversation partner was telling me the truth when she replied that she hadn’t heard of any of it. But I do remember that when I cited some recent examples of reports that he’d done this, she genuinely seemed caught off guard.

It was my first encounter with what I suspect is selective hearing among that faction of voters, so shocking in its first days, and so utterly commonplace now. It was my first hint at what was to come in America’s relationship to itself and its apparent favorite billionaire, and how alive it has kept the conditions of subjugating and disposing of vulnerable people, particularly women, before trotting out these ploys to other groups.

It was the first time I began to understand Trump’s uncanny ability to weaponize people against themselves.

***

I remember saying to this woman, “I’ve been sexually assaulted,” and her face going to stone. I remember telling her that I couldn’t vote for someone who had been accused of violence by so many.

Full disclosure: I’d drafted and finished this piece before Matt Gaetz withdrew from consideration for Attorney General, reportedly after Trump told him he couldn’t muster the votes in the Senate to approve his appointment. However, I’m not convinced this temporary gesture towards some level of respectability is going to stick, as Gaetz is one of Trump’s favorite foot soldiers. I think it’s more likely that Trump will appoint someone he will ultimately fire in three to six months; and once re-installed in office—once the current hoopla has eroded in the national media-cycle memory— he’ll swiftly move to re-instate Gaetz. Especially with a Republican senate majority, and in the full throes of his chaotic strongman governance, this will encounter less resistance.

Matt Gaetz is not qualified to be America’s prosecutor, nor really anyone else’s, but that should hardly come as a surprise. When my dad delivered the news over the phone, he asked me to make a guess who Trump had chosen for Attorney General, adding the clue that it was the worst possible person. But after my answering “Giuliani” fell flat, I told him I legitimately had no idea.

Of course it was Gaetz, who has only ever went to trial a handful of times on record and is one of the most hated men in the house (but who also retained 66% of the vote in his recent re-election bid.)

What I was more surprised by—honestly—is that this was met with a certain level of shock and resistance within the Republican Party, but that bespeaks my own ignorance toward the various social dimensions at play in that realm. Since the Thursday after the election, my brain has more or less decided (in moments where it’s not feverishly plotting out strategy for what’s to come) that we live in a reality show now, a self-fulfilling prophecy in the age of the attention economy. Gaetz would have, and still may, make a great villain arc for this season—he’d give Omarosa a run for her money.

It was later, as I was scrolling through an oddly satirical Fox News post about the appointment, that I clocked the proximity of Gaetz’s appointment to the release of the “damning” House Ethics Committee findings from a three-year-long investigation into his alleged sexual improprieties and drug use, scheduled for hours after he resigned from Congress. In a way that so many of us whose screams about misogyny have disappeared into the vacuum of wider social programming are well-versed in, I winced when I realized that this was likely his victim’s last shot at holding her inexplicably powerful, moneyed exploiter to account after the Justice department had declined to press charges. That the DOJ did not find reason to indict Gaetz, I guess, could technically mean he’s innocent. Also true: innocence is often an interpretation of circumstances by powerful people within an institution, who are usually men, and who have a hard time not being biased in this way, no matter their personal beliefs. (However, fascinatingly, it appears that legal files with testimony to back her up have been hacked—which may hold some hope for further generation of public pressure towards accountability in these circumstances.)

It may not require a trained eye to recognize the ease with which white males can manufacture plausible deniability in the criminal justice system. But it certainly helps. I’m a researcher-in-training who leans hermeneutic phenomenological, which is an overly academic way of stating (in a way that scares off many other researchers) how deeply crucial context is in evaluating and understanding data. Allegedly, for a time Gaetz made a habit of attending parties held by his then-buddy, where copious alcohol, drugs, and prostitutes circulated. One of these prostitutes (only identified in court records as “A.B.”) was still in high school when they met, which apparently he was aware of; Gaetz, after being witnessed having sex with her at one of these parties, was even allegedly told to “steer clear” of her. But he didn’t do this, and requested to be linked with her again some time later, after she had turned 18. The “sex trafficking" of it all was Gaetz paying for her to come with him on out of state trips, which wasn’t unusual for him. Oh, and we have records of this alleged activity in the form of Venmo payments, numbering in the thousands of dollars.

The risks for victims pursuing accountability are real, which to me, makes this whole schlock all the more devastating. Sex trafficking, which ironically has become a politically viable cause-du-jour for some factions within the Christian right, doesn’t happen the way viral narratives paint it. In fact, a lot the current hysteria about trafficking actually undermines its prevention by planting false red flags in the public consciousness. While the traditional “kidnapping and held hostage” trope does have some basis in dark, seemingly random acts of violence, it is four times more likely that trafficking happens between people who know who each other and have a pre-existing relationship, namely family and intimate partners.

This tracks with the statistics about sexual assault, wherein 80-85% of rapes happen by someone the survivor knows. Mull on this for a second— and then, as you scan the landscape around Gaetz (the future president’s first choice for the highest law enforcement arm of the government), consider that 99% of sexual offenses are understood to be enacted by men. Only 2% of men accused of rape are ever convicted and imprisoned. What this means for survivors is complicated, and entails a lot of creativity to metabolize the physiological and psychosocial repercussions of being profoundly violated. In a culture that still prioritizes the feelings and identities of men—a culture that the Trump administration seeks to reinvigorate with all this fresh hell—denial and shame are shockingly experienced as easier than living with the pointed, sharp loose ends of such violence.

My brain has more or less decided (in moments where it’s not feverishly plotting out strategy for what’s to come) that we live in a reality show now, a self-fulfilling prophecy in the age of the attention economy. Gaetz would have, and still may, make a great villain arc for this season—he’d give Omarosa a run for her money.

The machinations of American politics, where rumors of sexual impropriety can end careers as quickly as a published tweet, have nonetheless primed us to mostly dismiss the crimes of those who either act as or are in the favor of our elected leaders. While it’s easy to distinguish this within the MAGA movement, it is also something relevant and sometimes unexamined on the left. My father’s confidence in Joe Biden has always been precarious due to his egregious performance as chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee during the Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill hearings, now more than thirty years ago. There is persuasive evidence that Bill Clinton—who is still trotted out of retirement to comfort the donor class he helped build into the infrastructure of the Democratic Party— preyed on more women than a 22-year-old White House intern named Monica Lewinsky.

In a move I find darkly funny, one of the star witnesses in the Gaetz case—Joel Greenberg, the former friend who orchestrated much of this at the congressman’s request—was dismissed by Gaetz as a non-credible actor for lying about a previous political rival doing something that Greenberg himself went to prison for. Greenberg was running for the tax collector seat in his county, and smeared his schoolteacher opponent by manufacturing stories about inappropriate relationships with his students. Greenberg is now in prison after being indicted for 33 criminal offenses, including stealing $400,000 of taxpayer money to buy sports merch and crypto, stalking the aforementioned political rival, and trafficking the same victim named in the Gaetz case.

Greenberg ultimately cut a deal allowing him to plead guilty to six of the charges and serve an 11-year-prison sentence, in exchange for cooperation in the investigation of Swampy Matt. Still, Greenberg’s judge was quoted in the NYT as saying “in 22 years, I’ve never experienced a case like this…I have never seen a defendant who has committed so many different types of crimes in such a short period.”

Perhaps the gavel of justice came down all the more heavy on Greenberg for the “Florida Man” of it all. I’ve been lately thinking often of the Martin Luther King Jr. quote that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” The current arcs of said moral universe are unknown to me, to be totally honest, as someone who spends a lot of time studying climate change’s impact on mental health (a disaster decades in the making). But the floor, at this junction, seems open.

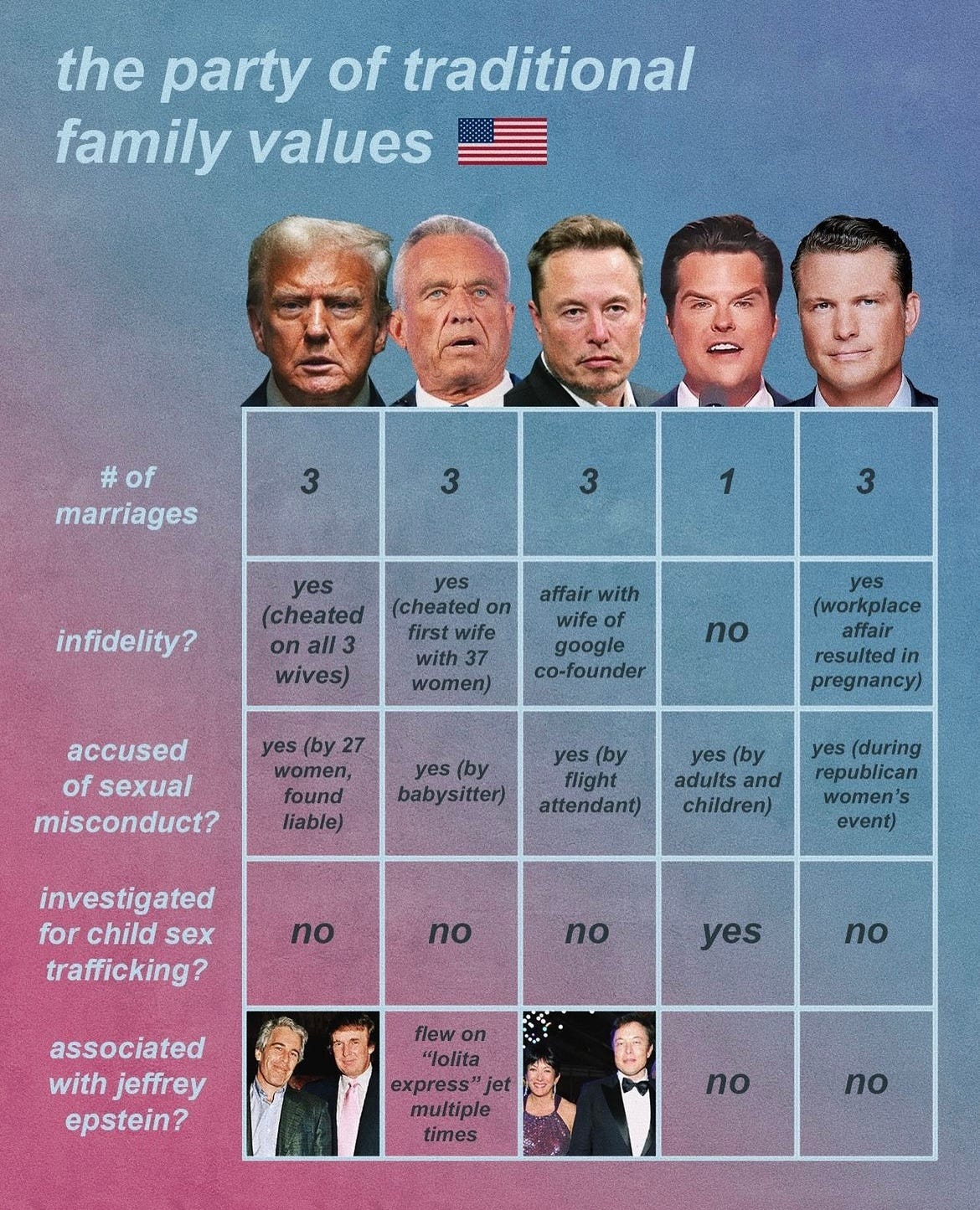

As such, Gaetz wouldn’t have been outlier figure in Trump’s posse cabinet. The inner circle is populated by several other creeps chosen by a man that Jeffrey Epstein thought he might be the closest friend to. Robert F. Kennedy Jr’s track record with women is queasy at best, and he responded to assault allegations by texting the victim a damage-control denial thinly veiled as an apology. Pete Hegseth reportedly trapped and raped a woman in his hotel room, then paid her off to protect his post as a Fox News anchor. The nominee for Education secretary, with her husband (also a man accused of predation and assault), was sued last month for working to cover up a number of sexual exploitation incidents within the World Wrestling Entertainment venture over a period of several years.

I think fellow survivor (and literary powerhouse) Roxane Gay’s diagnosis that no amount of scandal will deter the core voting bloc behind Trump is correct. I think she is incorrect, though, in assuming that much of its unstoppability comes down to choosing conjecture and fantasy, at least in the service of believing Trump’s innocence. Despite juries which have included a former supporter of his finding unanimous fault on his part in a host of criminal acts, the ecosystem he sits atop is very good at hooking and exploiting the worst fears and impulses of low-socioeconomic status communities nationwide to further their narrative. He knows how to sound credible to a population disillusioned by governmental authority in maintaining that he is the perpetual victim of a witch hunt.

To be frank, the Democrats don’t seem to display an investment in the well-being of rural and low-social economic status citizens that could outweigh the amount of fear-mongering their counterparts on the right foster. The right-wing media has done a horrifically effective job at scapegoating immigrants and trans people for the economic disparity these folks experience, while the left continuously tries to sell them on policy that makes more sense for middle-to-upper class metropolitan voters. This has been executed so well that precarious polling data suggests members of even the most targeted groups helped vote Trump back into office (though I think when the Pew data comes out next year, it will confirm the more realistic reality that it was probably mostly white people, again.)

And this is where we get into the thick of it— the deeply uncomfortable reality we now live in, where I hear and read a barrage of voices asking “how do these voters work against their own interests?”

It was my first encounter with what I suspect is selective hearing among that faction of voters, so shocking in its first days, and so utterly commonplace now. It was my first hint at what was to come in America’s relationship to itself and its apparent favorite billionaire..It was the first time I began to understand Trump’s uncanny ability to weaponize people against themselves.

I don’t think the answer is fantasy for most. I think it’s just the planted seeds of mass scapegoating that have captured the fears of a voting base and monopolized their activated survival mechanisms. The level of dissociation and denial may look weird to the average layperson. Those who’ve had to live with the crimes of someone who was once trusted know that it’s more complicated than that—it’s ridiculously slower. And it often requires the very patient, firm footing of an outside influencer (or community) who can credibly foster the notion that maybe, the world can be trustworthy again. Trump and the apparatus around him have done an incredibly effective job at making sure that those voices don’t exist where anyone in their base can hear them. The nomination of so many normally un-electable, unqualified, dangerous people to high level positions is meant to subjugate the spectators. His need to constantly create chaos, appoint loyalists, and feverishly insist they are his “best people” is imprinting the pattern on lawmakers and the public of how he wants to govern. Like many perps, it’s an expression of his ultimate goal: to achieve dominance.

What is so known to those of us who have to absorb our trauma and attempt to live without further loss is the very beginning of the fascist playbook, and is the basis for relationships predicated on coercive control. The Trump-public dynamic has always bled the sludge of power dynamics found in situations of domestic abuse. I don’t think Trump is a genius for pulling off shit like this; he’s just something much more boring— a bullish manipulator offering a reality rooted in the repressive patriarchy that humanity still hasn’t fully surmounted. The people close in his orbit—the authors of Project 2025—are scarier to me, with the depth of conviction they display that subduing and eliminating the rights of everyone but white, American-born men will “make America great again.” And even scarier to me is the way that they are able to sell this vision to individuals who will likely lose many of their rights in the coming years. But it also looks familiar, in that people who are exhausted by what’s been taken from them will learn how to side with their oppressor as an act of mental survival; it is much easier to fight ourselves than against those in power.

Trust me on this. Take it from someone who still often feels unable to call herself a ‘victim’ most days. Society decided a long time ago we weren’t truly going to commit, en masse, to the messy discomfort of truly believing and honoring victims, (unless they fit a specific, convenient template.)

But who knows? Under this administration, maybe it will become how we learn to resist.

—afc

Previous Rhubarb pieces by Audrey: Close Encounters with the Mirror World, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

Wonderful.

Audrey, thanks for this incredibly well-said commentary. I was living in an abusive marriage during Trump's first term. The coercive control and cognitive dissonance are so loud.

I am now divorced. I am not looking forward to the next four years. -Anna