Tightly-turning Western Bluebird

Linda Greenhouse and the search for “America”

From the swirling sargasso of the dream world, I awoke Wednesday morning with Linda Greenhouse on my brain. If her name rings familiar, it’s likely you’re about my age, and grew up, as I did, with an interest in current events in general and perhaps the law in particular.

Ms. Greenhouse is one of a half-dozen or so journalists I’ve followed (Nina Totenberg, Adam Liptak, Dahlia Lithwick, Jane Mayer, among them) who’ve helped me keep up with national legal controversies. She is best known for her work, over thirty years, writing about the Supreme Court for the New York Times. She was deservedly decorated with the Pulitzer Prize in 1998. Now in her mid-seventies, she still contributes occasional columns on legal controversies.

Linda Greenhouse at a 2019 lecture (Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

She came to mind Wednesday morning not for anything she’d written, but for something she said seventeen years ago.

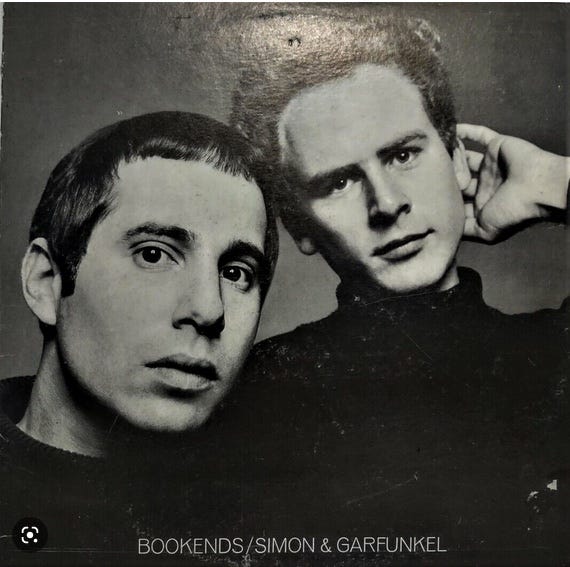

It was September 2006. She was giving a speech at Radcliffe, where she had studied, and where she was then receiving an award. After politely giving thanks, she told a story, not about the law, but about a sudden plunge of emotion she experienced while sitting next to her husband at a recent event in Boston. It was a Simon & Garfunkel reunion concert, a festive evening and a happy one for her until the duo sang “America” from their 1968 “Bookends” album.

“America” is not a long song, barely over three minutes, but its un-rhyming lyrics are deeply evocative of youthful hope and vulnerability. At the end, the duo sings “Counting the cars on the New Jersey Turnpike. They’ve all come to look for America.” Then they sing, and repeat, “All come to look for America.”

When she told her Radcliffe (Harvard) audience about the concert moment in her 2006 speech, Greenhouse said she is not one who “cries at the tip of a hat.” So it surprised her that she started sobbing, and it surprised her all the more that she couldn’t stop—that she was in tears the rest of the night. It was, she told her audience, “a puzzling and disconcerting experience” and one that “in the ensuing days I worked hard to figure out.”

“America” was recorded in a year, 1968, that was both tragic and momentous. It galvanized a youth movement that pressed even harder on demands for an end to the Vietnam War and an end to abuses of racism, especially in the aftermath of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination that year.

“We were committed to the idea that when it was our turn to run the country, we wouldn’t make the same mistakes,” Greenhouse explained. “Our generation would do a better job.”

Yet, two decades later, the social movements for peace and justice had waned. The U.S. had gone to war with Iraq on the false claim that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction, the sadistic abuses at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq had come to light, followed by the leak of the CIA “torture memos,” the dismantlement of securities regulations that would invite the financial crisis of 2008 was underway, and, as Greenhouse knew well from her work on the courts, the judiciary was already being stacked with judges who would ultimately repeal the hard-fought gains in privacy and reproductive choice solidified by the Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade (1973).

“I cried that night out of the realization that my faith had been misplaced,” Greenhouse old her audience at Radcliffe. “We had not learned from our mistakes. We were not the solution, we were the problem.”

When she said that—when I heard her voice on the radio that September day in 2006—I could hear her voice cracking. It brought tears to my eyes, and I remember not being able to work for several hours afterward. Linda Greenhouse’s voice had affected me in much the same Simon & Garfield’s “America” had affected her at that concert in Boston.

I was left with the same hard question: why?

There’s a bit of nuance here. It matters that both Greenhouse and I are journalists. Our professional code asks us to keep a discernible distance between our personal feelings and our subjects, so much so that reporters are regularly censured for attending political rallies on their off days, or even wearing politically-messaged apparel. My former reporting partner and I would regularly try to remind each other that we’re only visiting the zoo with our notebooks; it’s not our job to leap the fence to break up fights between the animals.

Over time, I used my skills as a researcher and writer in work for social change organizations—working to expose Hanford’s dark secrets, working to change the laws that allowed its plutonium mills to be exempt from dangerous waste practices, working to change Washington’s agricultural burning rules to better protect vulnerable adults and kids with chronic lung diseases like cystic fibrosis, etc.

Still, the core of my career has been in journalism.

The reality is that Linda Greenhouse and I became reporters for the same reason—our inspiration to do journalism was informed and motivated by our devotion to the concept of community, our desire to be useful in making our readers more informed and more aware, and (we trust) more humane. That’s it. There are valid reasons we shouldn’t wear that on our sleeves while we do our work, but that’s essentially it—we’re invested in The Enlightenment, such as it is; the hope that it’s more likely reason and compassion and truth can prevail if we do our jobs well.

I’m not a psychologist, but I suspect the reason “America” got to Linda Greenhouse is the same reason her message, with that cracking voice, ripped me to my core. Like countless other Americans who lived through that era, we heard the same music. It inspired us to believe we had a calling beyond our own security and prosperity.

I’m a bit younger than Linda Greenhouse (I was 11 in 1968) and probably more influenced by Watergate than Vietnam—although there was courageous reporting about Vietnam that helped bring an end to that painful misadventure. There’s a straightforward connection between the investigative journalism (Woodward & Bernstein, et al) and the fall of Nixon’s ghastly presidency, with its burglaries, and cover-ups, and enemies lists. My uncle Barrie was in his prime as a newspaper editor at the time and was one of the editors behind the formation of the Investigative Reporters and Editors organization. It’s what I wanted to do.

I did much of my best work before I became a father, but being a father only heightened my desire to do better work, and especially work that could benefit my community, in the broadest sense. Ultimately—and regardless of our chosen careers—we are either committed to being in this together, or not. It’s not a choice we can hide from, or be absolved from. From the good years, I admit I developed a swagger of confidence. It really seemed as though I was living in and contributing to a world that was improving not just in its capacity to solve material problems but to install the moral infrastructure that justice and peace require. Yet, by 2006, I felt as Greenhouse felt. I just hadn’t admitted it as plainly as she did that day.

Greenhouse caught grief for her 2006 speech primarily because she sharply criticized the Bush Administration. (You can hear and read NPR’s report on her speech here, and it includes a link to the audio of her Radcliffe address.) That her speech included sharp criticism of political choices is noteworthy but it actually begs the deeper issue. It’s not just that she’s entitled to her opinion, it’s that the quality of her work, by itself, refutes the notion that journalism fairness somehow relies on journalists being 24-hour agnostics when it comes to politics.

I believe in professional standards as much as anyone. Whether we are journalists or doctors, or mechanics, it’s part of our compact with society. But we are no more capable of shielding our eyes and ears from our emotions than we are able to leave our hearts under the bed when we put on our shoes.

When I heard Linda Greenhouses’s voice crack that day in 2006, I heard the heart and soul that brought forth, and still does, her hope that we can leave the world a better place for having been here. It was not a bad thing to wake up to her voice in my head yesterday morning. It didn’t bring tears to my eyes. But it did remind me that I’m still deeply grateful for her work, and her honesty. It actually gives me hope.

—tjc