Thursday's postcard, and flickers of progress in citizen oversight of the West Plains "forever chemical" fiasco

September 19

Ring-billed gull in flight above Banks Lake in Upper Grand Coulee

Democracy at the gates

Instead of calling this a confession, let’s call it a disclosure. I have not sinned but, I’ve swerved.

My preference is to do journalism, but journalism (especially at the regional and local levels) has been in crisis for the past forty years or so. You may have noticed this. After Spokane Magazine (the first one) collapsed during the recession of the early ‘80s I took a part-time job selling theater tickets so I could continue doing what I’d been doing at the magazine—primarily investigative reporting.

At Spokane Magazine I’d gotten a reportorial foothold into the morass at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation and, after the magazine’s demise, continued that work as a freelance writer for the Seattle Weekly and other regional publications. I had reliable sources and Hanford had big secrets, including (at the time) long-suppressed records documenting startling releases of radioactive and chemicals from the plutonium factories built in the desert west of Richland as part of the top secret Manhattan Project. Hanford’s plutonium operation had more than doubled in size during the 1950s, during the Cold War.

Fence line at Hanford tank farm storing high radiation wastes from plutonium extraction

When the long-secret files were released in 1986, they vindicated the reporting and helped catalyze a regional citizen movement that included HEAL, the Hanford Education Action League based in Spokane. By that time I had been hired by HEAL to be their staff researcher and to represent the group in regional and national forums. In that role, I testified before both houses of Congress, served on three federal advisory committees, and helped instigate what is now the national Alliance for Nuclear Accountability, a nationwide network of citizen groups that promotes transparency and accountability at the nation’s nuclear weapons production complex. Life went on, pretty much in that fashion—back and forth between writing and public interest activism until I had to devote myself, full-time, to caring for my ailing parents, both of whom have since passed away. Presently, I work for the paid subscribers to The Daily Rhubarb. ( And while I’m at that, thanks to all of you who’ve chipped in. I couldn’t be here without your support.)

Today’s article is freely available in full as a public service, but please consider becoming a paid subscriber to The Daily Rhubarb at the link below. Subscriber support makes this series possible. tx, tc

My present sometimes bumps into my past and so it did shortly after I began reporting on the West Plains “PFAS” water contamination crisis in the spring of 2023. I had been invited, in the early 1990s, to be one of a dozen “non-governmental representatives” on Federal Facilities Environmental Restoration Dialogue Committee (FFEDRC) a new federal advisory committee convened by EPA but with essential representation from the U.S. Department of Energy and the armed services. As the New York Times was reporting at the time, there was escalating public unrest, from coast-to-coast, with the legacy of contamination and secrecy at defense facilities (i.e. the Rocky Mountain Arsenal just east of Denver) and nuclear weapons production facilities (i.e. Hanford) managed by the U.S. Department of Energy. The goal of the new advisory committee was to improve and streamline compliance with state and federal environmental laws, but also find ways to better engage and protect communities who were bearing the brunt of the risks posed by living immediately downstream, down-gradient and downwind from radioactive and chemical wastes that had piled up for decades.

The barriers weren’t just fences and guard towers. In the early 1980s, for example, it was still illegal, under Washington law, for state environmental inspectors to go onto the Hanford site without the permission of federal officials. This was one of many signals of how the Hanford site’s economic importance to the Tri-Cities offered a “halo effect”—essentially a shield of local economic support that discouraged dissent and inspection. That changed in communities downwind and downstream of Hanford after the 1986 revelations and led to the landmark Hanford site cleanup agreement in 1989, the first and most expensive cleanup agreement of its type.

In short, the process I joined in 1992 was to help ensure citizen leaders were represented, informed and better positioned to have meaningful input into cleanup decisions that could affect the health of their communities for generations to come. It was a profound culture change and much of the credit for our success goes to Thomas “Tad” McCall, the lead U.S. Air Force representative on the committee.

If the name seems familiar, it’s because McCall’s father, Tom McCall senior, was the Republican governor of Oregon from 1967 to 1975. Governor McCall’s signature achievement was to rescue the badly polluted Willamette River that passes through Eugene, Salem and Portland on its way to joining the Columbia just west of Vancouver, WA.

I remember at least a couple occasions during our work when Tad, often in uniform, cleared his throat to speak in full command voice to the other military reps at the table. You can imagine the context. The command and control culture of the military is mission-oriented, insular and rigid. But McCall would remind his military peers that their fundamental calling was to protect the American people, and that included protecting their communities from harmful contamination. It was inspiring to hear and watch, and it made a difference.

Our report wound up being over 150 pages long, but a centerpiece recommendation was for what we termed “Site-Specific Advisory Boards” that would inject public review and recommendations into cleanup decisions in real time.

The oldest of the boards—the Hanford Advisory Board—was created even before our final report was published. There are seven other advisory boards at Department of Energy sites, but more than 200 “Restoration Advisory Boards” (RABs) at Department of Defense sites.

Fairchild Air Force Base was added to the federal “Superfund” cleanup list in 1989 due to soil and groundwater contamination with trichlorothylene (TCE) a common solvent used primarily as a de-greaser. The base has had a RAB since April 1995.

I knew about the Fairchild RAB but hadn’t attended a RAB meeting until March of last year, as I was gearing up to do reporting on the West Plains “forever chemicals” story. In early 2017, a Fairchild employee notified a RAB member who worked for the regional health district that PFAS “forever chemicals” had been discovered in base groundwater. Since then the presumption has been that firefighting foams used at the base are the major source of the PFAS chemicals that have contaminated much of the West Plains groundwater. (Nearby Spokane International Airport is also a source of PFAS in West Plains groundwater, though the investigation into the extent of contamination is still in its early phase.)

Long-time West Plains resident Gayle Meyers speaking before a packed room at the Fairchild RAB’s “listening session” in April.

The site advisory boards the FFERDC spawned have had understandably disparate experiences. As you’d expect, local politics and culture vary from site-to-site and those differences affect the tenor and effectiveness of public input. Still, I was struck by how perfunctory the Fairchild RAB meetings were—orderly to be sure, but with abbreviated discussions on what seemed to be key questions and issues. Even basic explanations for crucial decisions affecting scores of well owners—such as the Air Force’s decision to render assistance to owners of contaminated wells west of Hayford Road (a busy north-south thoroughfare that bisects the West Plains) but not to those with PFAS contaminated groundwater east of the route—were absent for months at a time.

Six years into the PFAS contamination debacle there was, and still is, public confusion and fear, much of which was on display at “listening sessions” the state hosted in the spring of 2023 and one the RAB hosted in late April of this year. In retrospect, part of the reason was no fault of leadership at Fairchild. At least the Air Force had disclosed and acknowledged its problem, while officials from the Spokane Airport were as silent as they were scarce.

A few weeks after the lively RAB listening session I attended one of forums hosted by the West Plains Water Coalition in Airway Heights. I noticed that Jaclyn Satira, the U.S. EPA lead on the Fairchild cleanup and the agency’s representative on the RAB, was seated nearby.

Journalists should not make a habit of offering advice to public officials, but I decided it was okay if I wrapped my suggestion in the form of a question. As the meeting wrapped up, I introduced myself and asked Satira if the RAB was familiar with the work and operations of the Hanford Advisory Board. It was a politely loaded question in that the Hanford Advisory Board (HAB) is well known for its size, diversity and formal protocols for offering, tracking, and monitoring responses to its recommendations. Satira raised her eyebrows and smiled. It turns out she and Megan Riccobono—the on-site lead for the Air Force Civil Engineer Center which manages the base’s environmental response and restoration activities—had made a trip to Hanford just days earlier, to study the Hanford board’s work and procedures.

That was a good sign and it was an even better sign when Riccobono briefed the RAB when it met, a few weeks ago, in late August. Her first topic was a report on her visit to Hanford and what she and Satira had observed. She described the HAB as the “standard” for the advisory board model and spoke with enthusiasm as she described what she’d learned. She offered to lead a process to determine if he Fairchild RAB would “somehow like to incorporate” practices of the Hanford board into its process. Several of the items would be housekeeping improvements like providing microphones for each member during meetings, but others would change the nature of the board’s work—i.e. allotting time at each RAB meeting to hear reports from board members about community concerns and feedback from those affected by the PFAS contamination.

To their credit, Riccobono, Satira and the board’s community co-chair, John Welge, seem sincerely eager to sharpen and empower the RAB’s role. Indeed, the first order of business at the RAB’s August meeting was to formally add two active and well-credentialed public members—Jerry Goertz, the manager of a rural water district north of the base, and Chad Pritchard, the Eastern Washington University geologist (and Medical Lake city council member) who’s already playing a key role in tracking and modeling the spread of PFAS in West Plains groundwater. (Earlier this year the board added local government and tribal representatives.)

Another noteworthy addition to the RAB board is Nick Acklam, a top manager in the state’s toxics cleanup program. It was Acklam who took the lead in serving the Spokane Airport with an enforcement order last year, after Ecology obtained documentation about PFAS contamination in the airport’s groundwater.

Acklam’s presence is telling. The state’s jurisdiction at Fairchild is limited to cleaning up petroleum spills. But the reality is Ecology has jurisdiction and an urgent role to play right across the road (Hayford Road) that defines the eastern edge of the Air Force’s jurisdiction. The road is the boundary between two dramatically different government responses. Whereas the Air Force publicly acknowledged Fairchild’s PFAS contamination in 2017 and moved to address it, the Spokane Airport (jointly operated by the City of Spokane and Spokane County) chose silence. When Ecology notified the airport management last year that it was bringing an enforcement action under state law, the response was defiance.

Last February—building upon the public outreach efforts of the non-profit West Plains Water Coalition—Ecology and EPA, with support from the state Department of Health, moved to provide emergency assistance (well testing and free bottled water to those whose water was contaminated) to private well owners on the east side of Hayford Road. The well-testing confirmed what was already apparent to many of the property owners, some of whom had been privately paying to test their water for PFAS—the PFAS contamination was widespread and appears to emanate from the Spokane Airport.

There’s no law that requires the Air Force, EPA and Ecology to communicate and coordinate across jurisdictions. As an Air Force official clearly (though regretfully) responded to a well owner east of Hayford Road last November “(a)ccording to Department of Defense policy and Federal Fiscal Law we are expressly restricted from spending DoD funds on non-DoD sources of contamination.”

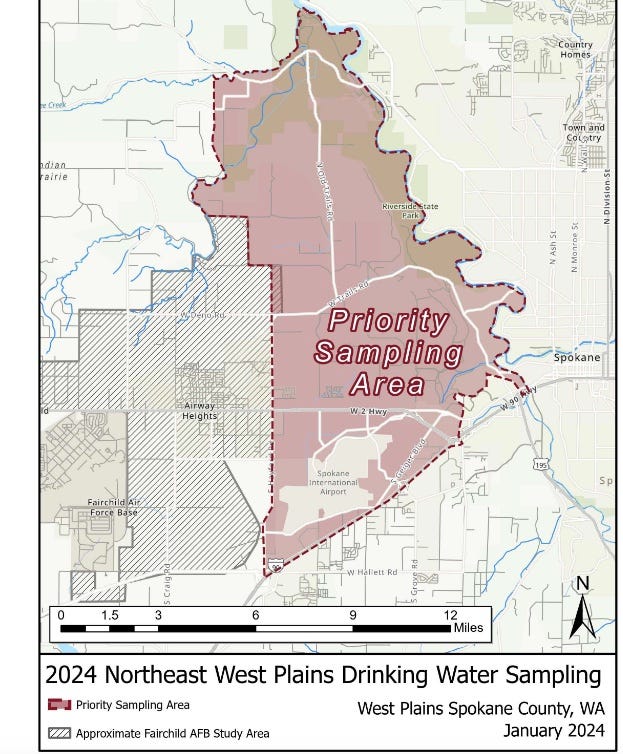

Map showing (in red) the area near the Spokane Airport (outside Fairchild’s PFAS response zone) where federal EPA and state environmental staff collaborated on an emergency effort to test private wells and provide safe drinking water this year.

Yet, the reality is that the West Plains is one large neighborhood struggling to deal with PFAS contamination on both sides of the road, so to speak. While funding for the needed assistance may have to come from different pockets, communication between the agencies—and with affected and concerned neighbors—is crucial and cost-effective.

For example, this spring the federal EPA finally issued its final drinking water rule for PFAS, setting the standard for the most common PFAS variants at 4 parts per trillion (ppt). The 4 ppt standard is considerably lower than the action level of 70 ppt the Air Force has been using for years as its action-level for providing assistance to well owners whose water has been contaminated with PFAS from Fairchild and other installations.

As I reported on September 10th, the DoD response to EPA’s new standard was to announce that it would set its remediation action level at 12 ppt, a number that Fairchild has confirmed it will use, going forward, to evaluate and re-evaluate when it will provide assistance to those whose well water tests positive PFAS. Whether the 12 ppt is the last word is not yet clear, but whether it is 12 ppt or 4 ppt, it will force changes in Fairchild’s program.

In reply to a written query about the new standard (the Air Force has declined my request for an interview) the Fairchild media office provided this written response:

“The Air Force is reviewing existing PFAS sampling results at Fairchild AFB, and will be expanding existing cleanup investigations including additional sampling, and providing drinking water treatment for impacted off-base wells, on a prioritized basis. Since a significant number of additional wells will require treatment, [the] Air Force will first prioritize locations where known levels of PFAS in drinking water from Air Force activities are the highest. To expedite implementation of more enduring solutions, [the] Air Force will focus on installing treatment systems, such as whole house filters. The community will be kept informed of expanded sampling areas and mitigation through RAB meetings.”

If the good news is that more well owners stand to get assistance from the Air Force under the adjusted policy, there is still the quandary of where the lines are, both geographically in terms of where FAFB assumes responsibility for contamination (versus the Spokane Airport) and what level of contamination triggers the response.

In other words, it’s just the sort of conundrum that local/regional advisory boards were created to address and why the re-tooling and expansion of the Fairchild RAB is a vital and welcome development.

—tjc

Thank you, Tim, for this timely update.