A squadron of American White Pelicans on patrol in the skies east of Sprague, Washington, in eastern Lincoln County.

Atomic Hubris

In 1980 I was a very busy newspaper reporter for the Ellensburg Daily Record in central Washington. In addition to managing the Record’s darkroom, my beats included city police, the county sheriff’s department and its jail, the county commissioners, the Ellensburg school board. On Friday nights, I covered high school football games. I didn’t get much sleep that year, especially the week Mt. St. Helens blew its top and dumped several inches of volcanic ash into the valley, only 90 miles downwind from the eruption.

The most important story I encountered that year is one I brought with me when I moved to Spokane later that year. It was the story of the “Whoops” nuclear fiasco. “Whoops” is how critics, angry citizens and journalists began to refer to a hapless consortium, formally named the Washington Public Power Supply System, whose acronym was WPPSS. In short, WPPSS was a debt-issuing network of public utilities—including the City of Ellensburg and the Spokane-based Inland Power & Light Co-op—that was on a mission to build five large nuclear power plants, simultaneously

The WPPSS nuclear program started with a certain swagger and enjoyed the support of Washington governor Dixy Lee Ray (1977-1981) who, prior to becoming the state’s governor, had chaired the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. WPPSS was based in Richland, adjacent to the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, where three of the five large reactors would be built. (The other two were to be built near Satsop, in Gray’s Harbor County.) Large reactors had been built at Hanford since the 1940s to produce plutonium for nuclear weapons, though it wouldn’t be until the 1980s when we began to learn the extent of the environmental damage and public health risks the secret plutonium plants had brought with them.

To say the WPPSS nukes didn’t quite work out puts it mildly. The program became a regional debacle that led to what—at the time—was the largest municipal bond default ($2.25 billion) in U.S. history. Only one of the nuclear power plants—WNP 2, at Hanford—was ever finished. The stigma was such that WPPSS changed its name in 1998 to Energy Northwest.

I first got wind of the WPPSS fiasco a few weeks before I left Ellensburg. I’d lingered in the city council chambers after an evening meeting to finish up some of my reporter’s notes. So I was within earshot when one of the council members asked the city manager, Robert Walker, about WPPSS. What got my attention before I even understood what he was trying to say was Walker’s demeanor and voice. His normally calm, “just the facts” tone became increasingly animated as he spoke about his frustration and fear of dramatic electricity rate hikes. That’s what I remembered. The details were too complicated. His distress was not.

The WPPSS saga was awful for the region and the country. But it worked out pretty good for me. In early 1981, as a freelancer, I wrote the story of WPPSS’s impending collapse. It arrived as a 5,000+ word article for Spokane Magazine entitled “The Northwest’s $45 Billion Nuclear Catastrophe.” By that time, WPPSS was already more than $15 billion in debt, with none of its five plants nearing completion.

The upshot of the long article was this: WPPSS and the federal Bonneville Power Administration had used WPPSS-member ratepayers as unwitting economic hostages. In order to sell the bonds to fund the plants the men in suits had turned straightforward revenue bonds (bonds that would be redeemed solely by future revenues from electricity generated by the plants) into “hell or high water” securities—obligations that would tap directly into ratepayers’ wallets regardless of whether the WPPSS nukes ever produced a kilowatt of electricity.

The rate shock would be crushing. By the time my story appeared, the outstanding debt was well into the thousands of dollars, per customer. One of the poignant ironies of the WPPSS nuclear power program is that the rush to build the plants came in response to projections that the demand for electricity in the region would overwhelm the supply of hydropower from northwest dams. Yet, once the price of power began to skyrocket because of the WPPSS debt, the demand for the extra power plants quickly evaporated as the rate-shock and energy conservation programs took effect.

“The Northwest’s $45 Billion Nuclear Catastrophe” article is about the best I can do with forensic journalism. The reporting formed the basis and became a springboard for two more colorful stories of the WPPSS nuclear boondoggle featuring some of the more dramatic characters whose lives got caught up in this incredible, regional drama: “Hell & High Water in Ellensburg,” State Magazine, July 1982, and “The Cozy Co-op,” The Seattle Weekly, June 1983. Between the two you’ll get a very intimate look at how this very unnatural disaster unfolded and how people on both sides of the imbroglio responded to it at a community and personal level.

As the WPPSS drama burned like a regional wildfire, another story with deeper historic and moral refrains came to the fore at Hanford and Spokane. Ronald Reagan’s rise toward the Presidency in 1980 conflated militarism with patriotism. His election came with a tide of new federal money for nuclear weapons production, including hundreds of millions aimed at refurbishing and re-starting the sprawling plutonium production factories at Hanford that had been mothballed since the early 1970s.

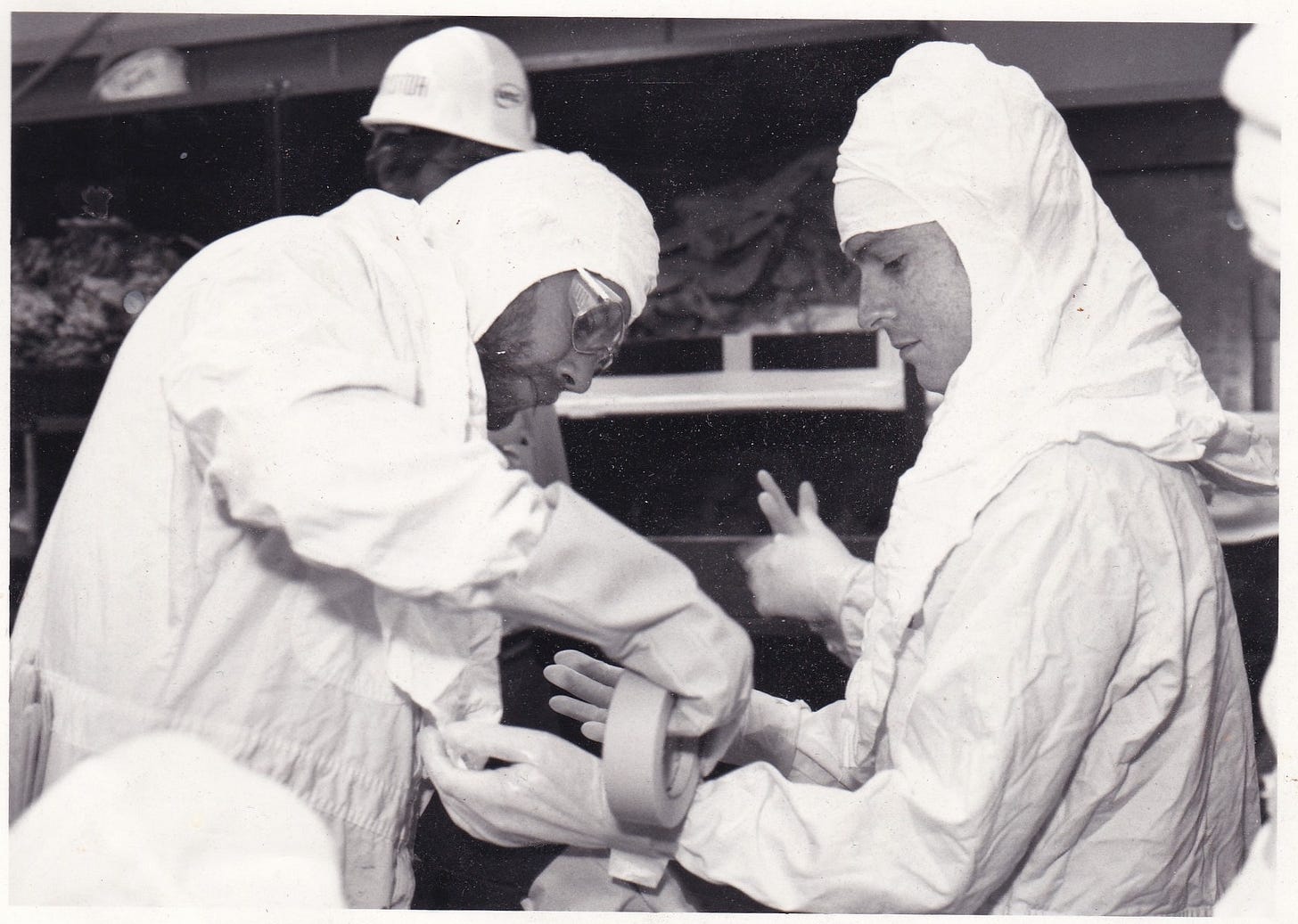

Getting fitted with radiation protection suit for a tour of Hanford’s “N” reactor in 1983.

On a regional level, Hanford’s return to plutonium production begged important questions about Hanford’s top secret past. The answers—residing in classified documents that were finally released in 1986— included revelations of massive releases of radioactive byproducts to the environment. I spent years digging into Hanford’s radioactive and chemical emissions as the staff researcher for a citizen’s group—the Spokane-based Hanford Education Action League (HEAL). But the best framing of the underlying moral questions is in a cover story I did for the Portland Oregonian’s (now defunct) Sunday magazine, NORTHWEST, in April of 1984.

The story is entitled “A Question of Conscience” and focuses on a few very brave Hanford scientists who rebelled against Hanford’s shift away from civil energy research back to nuclear weapons production work. It goes without saying that adding to a pile of nuclear weapons (in 1984, the U.S. arsenal, alone, had more than 20,000 nuclear weapons) is a profound, existential issue. Yet, on the pavement, at Hanford and the Tri-Cities, the day-to-day conversations about nuclear power and nuclear weapons were weirdly indistinguishable from the conversations about the economics of lentils, silver, and pork bellies.

As I was covering Hanford in the early 1980s I remember demonstrations involving thousands of Tri-Citians who descended on the WPPSS headquarters building carrying yellow ribbons—a symbol borrowed from the Iranian hostage crisis to show solidarity with the American embassy hostages in Tehran. One of the big signs in the crowd said “Unemployment is unAmerican.” For me it well-captured the extent to which all the Hanford nuclear projects—with their profound and inter-generational consequences—were driven in large part by parochial economic forces, one of whose prominent leaders was Glenn C. Lee, the long-time, firebrand publisher of the Tri-City Herald.

I was fortunate, for the Oregonian piece, to get a long, face-to-face interview with the legendary Sam Volpentest, whose name (along with Lee’s) is now attached to an interstate highway bridge over the Columbia, just east of Richland. He was as honest as could be about the role of plutonium in boosting the local economy, and his dismissal of those, including the bishops of his church (Volpentest was Catholic) who were speaking out against the resumption of plutonium production for nuclear weapons at Hanford.

The fourth piece in this package is “You Can Survive!” It’s a 1982 cover story for Spokane Magazine (in the Bloomsday issue, no less) that gets quite real about the U.S. government’s assumption that Spokane and Fairchild Air Force Base were high on the then-Soviet Union’s nuclear missile target list. Of course, the subtext of the story, as you’ll see, is that not even the civil defense planners assigned to Spokane really believed that a full-out nuclear war with the Soviet Union would be anything less than utterly devastating for Spokane and the surrounding county (not to mention the globe, in general). Fairchild hosted strategic bombers when I wrote this story, and the planes were about to be fitted with long range cruise missiles in addition to the nuclear weapons already fitted for their bomb bays. The bombers are no longer stationed at Fairchild but it’s reasonable to assume the air base remains on the Russian target list.

The series of articles, beginning with “Hell and High Water in Ellensburg,” will appear here on Thursdays, beginning next week.

—tjc

Purchase Beautiful Wounds, A Search for Solace and Light in Washington’s Channeled Scablands