Bewick’s wren, People’s Park, Spokane

Hell and High Water in Ellensburg

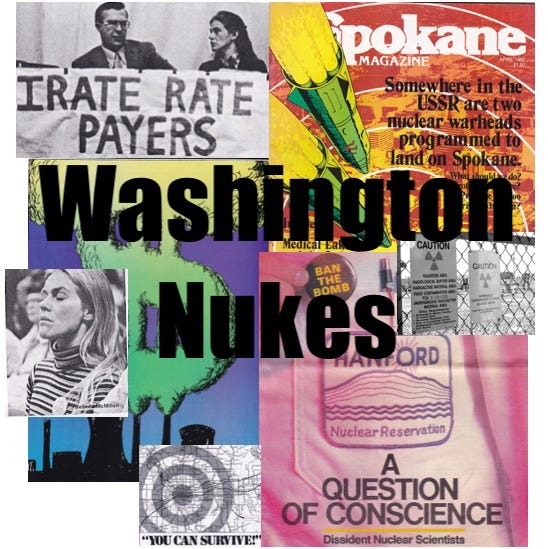

The people of one central Washington town discover WPPSS wasn’t selling nuclear power. It was selling them.

State Magazine, July 1982

Life is approaching flood stage in the kitchen of Belinda McMillen’s north Ellensburg home. She’s running late with the potato salad she is preparing for a friend’s surprise party, taking calls on the phone next to the refrigerator and trying to savor some of her favorite classical music while answering questions from a visitor seated on a stool in the dining room. There is a fragile balance to it all until her visitor starts playing devil’s advocate.

“Where were you back in 1976?”

The rhythmic thwack of her knife against the chopping board ceases, and it becomes clear from the look on her face that she is about to treat the question as if it were a housefly hovering above the cubed potatoes.

“Look,” she snaps. “There wasn’t enough press on this thing back then to fill a sheet of toilet paper.”

The blue pullover sweater catching her long blond hair has a red and white button clipped to it, that states simply, “I’m Irate.” Her explanation is captivating to say the least. It comes in a rambling, emotion-packed monologue delivered while the knife in her hand punctuates the air at least as often as it slices celery. The samurai effect is unintentional, but it’s clear “the powers that be” she berates would best be advised to stay out of her kitchen this afternoon. The edge in her voice is genuine and it cuts a swath from the the city council that meets on Pearl Street in Ellensburg to the financiers who meet on Wall Street in New York. When she finally pauses to catch her breath almost an hour later she rubs tears from her eyes and doesn’t try to disguise the fatigue etched on her face. For a long time now she says she’s felt like dropping everything to go backpacking up in the hills outside of town.

“Honestly, I’ve got no less compulsion than the next person to live my own life and not get involved. But I am involved.”

It isn’t the utility bill that angers her. While it is true the cost of electricity is going up in Ellensburg (this winter, rates may be more than three times what they were just four years ago) it doesn’t explain her metamorphosis from 37 year-old working wife and mother to local revolutionary. People upset about their power bills curse the local utility; people who talk fervently about changing the system and risk emotional exhaustion orchestrating rebellions have other things bothering them. And what bothers Ms. McMillen is this: for all the billions of dollars that had been borrowed and spent by Washington Public Power Supply System on nuclear power plants, none of the lenders was taking a risk with WPPSS or nuclear technology. What the Wall Street bond salesmen had really sold was the guarantee that no matter what, Belinda McMillen and her neighbors would pay up; that they return the investment—with interest.

What has become of nuclear power in Washington has not been good. The state has the dubious distinction of having the two most expensive abandoned nuclear power plants in the world. Because of it McMillen and the 5,000 other customers in Ellensburg will be billed more than $40 million over the next 3.5 decades—for nothing. Having learned she and her neighbors are expected to go along with this has made Ms. McMillen very difficult to reason with. In her own words, it’s made her sick to her stomach. Members of the city council complain about her disdain for protocol; the neighbors are experimenting with civil disobedience, and in Ellensburg utility bills have become tickets to a tunnel of mirrors from which there may be no way out. Getting in, on the other hand, was not as hard as it looked.

“Where were you back in 1976?”

The rhythmic thwack of her knife against the chopping board ceases, and it becomes clear from the look on her face that she is about to treat the question as if it were a housefly hovering above the cubed potatoes.

“Look,” she snaps. “There wasn’t enough press on this thing back then to fill a sheet of toilet paper.”

“Everything was more or less a solid concrete thing. A package.”

Randy Christopherson is Ellensburg’s mayor. A retired Puget sound Power and Light lineman, he is an amiable, impeccably polite gentleman whose political style is to let others ask questions, then vote with the majority. Of the discussions leading up to a particular city council vote the night of May 18, 1976, he remembers enough to remain convinced that the visiting experts from the Bonneville Power Administration and the Washington Public Power Supply System were very persuasive.

“They made statements saying that in order to be protected from blackouts and brownouts in the 1980s we had to join in, that there was no way they could supply power in the eighties without us participating. You could call it pressure if you want; what they were saying is that ‘You’d better jump on the bandwagon because this is the only assurance we can promise you that you’ll have enough power’.”

There was even more tangible evidence. It was only a matter of days after the city signed on as a co-sponsor for WPPSS nuclear plants 4&5 that Ellensburg received a letter it knew was coming: a formal notification from Bonneville Power Administrator Donald Hodel that after July 1, 1983, Bonneville—which still provides the city all its electricity—would not be able to guarantee Ellensburg’s power supply.

WPPSS 4&5 were also politically palatable. The plan called for all the expenses to be paid with borrowed money—no costs to ratepayers—until the plants were finished and generating electricity in the mid-80s. WPPSS borrowed and spent $2.25 billion; the customers it borrowed it for will, because of the interest, pay back over $7 billion, which in places like Ellensburg means hundreds of dollars a year for the average customer.

The council acted in good faith that night when it voted as the experts and the city staff warned it should, Christopherson says. Although the issue was “so be and so complex,” he and the others in the majority could see nothing wrong—then. “I still think it was the right thing, at that time. I have no regrets at all.”

The rest is history: the “bandwagon” became a paddy wagon with bars and windows. After more than five years and $2 billion spent, the scheme collapsed. Public outcry over enormous cost overruns, high interest rates, and the demands of nervous Wall Street financiers suddenly crumpled the rather bizarre political and financial gearboxes that drove the construction of WPPSS 4 & 5. After a series of confusing events in boardrooms and commission chambers around the Northwest, the proper word for what was to happen was delivered to the public. The two unfinished nuclear plants would be terminated—technological euthanasia.

Now, the formula that had made 4&5 so palatable—borrow now, pay upon the delivery of electricity—has suddenly become political dynamite in places like Ellensburg. Last May the city-owned utility added a 40 percent surcharge to bills in order to raise the $1.1 million a year required to meet its 6/10 of 1 percent share in WPPSS 4&5.

The reaction to the rate hike even caught Ms. McMillen by surprise.

“This is not an activist town,” she says. “And that’s the understatement of the month.”

But last February, after she’d done her homework and saw it was time to find out how others in town felt about the matter, she reserved a large room at a nearby junior high school and put an ad in the local newspaper. She was afraid nobody would show; by her count close to 400 did, and Ellensburg hasn’t been the same since.

The historic Davidson Building (1890) in downtown Ellensburg, at the corner of Fourth & Pearl.

Having learned she and her neighbors are expected to go along with this has made Ms. McMillen very difficult to reason with. In her own words, it’s made her sick to her stomach. Members of the city council complain about her disdain for protocol; the neighbors are experimenting with civil disobedience, and in Ellensburg utility bills have become tickets to a tunnel of mirrors from which there may be no way out. Getting in, on the other hand, was not as hard as it looked.

When the ratepayer explosion hit Ellensburg last winter it was ironic that it would quickly claim Larry Nickel as a casualty. Nickel had been the most outspoken critic of WPPSS on the Supply System board; the same WPPSS board members who sinned against the system by voting for Initiative 394 giving voters veto power over WPPSS bond sales; the same politician who says he’s all for finding a way for Ellensburg to escape it’s share of WPPSS debt. He’s now local enemy number 1 of the Irate Ratepayers.

“They’re angry and they’re frustrated, sure they are,” says Nickel, who quietly won re-election last fall to the city council in a campaign in which electricity was not even an issue. “But let’s put it this way—it’s just too bad their energy is being expended in such a negative way. They don’t see the sequence of events that needs to take place to try to get us out of this.”

Unfortunately for him, one of the things the Irate Ratepayers have seen is Nickel’s dismal attendance record at WPPSS board meetings published in their newsletter. His rather flip response that the WPPSS job was something he volunteered for only adds to their strong feelings that nobody has been looking out for them. That fact, combined with their distaste for Nickel’s brash (they call it “arrogant”) style, plus his simply being seen as a point man for the city on the issue, has put Nickel, the critic of WPPSS, in the rather warped position of being considered an opponent of the Irate Ratepayers. He’s even getting a cold shoulder from the senior citizens (who, as a group, make up a good share of Ellensburg’s angry ratepayers) in his neighborhood.

“They’ll talk about other things. But as soon as the discussion turns to electricity, they want nothing to do with me.”

Nickel is right about one thing: Ellensburg’s Irate Ratepayers are not interested in a “sequence of events” that has them paying while the city probes for a legal way out of its obligations to WPPSS 4 & 5. They want the city to drop the WPPSS 4 & 5 surcharge from their bills, now. From their perspective it was, after all, a supposedly prudent “sequence of events” that caused the mess in the first place. And although there are few angry ratepayers with good alibis for not having seen earlier how the shaky plight of WPPSS was inevitably going to jack up their utility bills, Nickel for the past two years has had the advantage of a reserved front row seat at the making of a quagmire. He could watch as a technological and economic catastrophe was shaping itself, one faulty assumption, one piece of ego, one cost-overrun at a time.

Having suddenly been handed the bill for a fiasco, the Irate Ratepayers in Ellensburg are not particularly interested in a solution that takes time. Although Ms. McMillen and the other leaders of the group have tried to provide information on the city’s involvement with WPPSS and WPPSS itself, the education hardly has a calming effect. Recalling his presentation to the group, CWU professor Dr. Ken Hammond—one of the most astute critics of Northwest power planning—said he feared his message didn’t get through to the emotional audience.

“All they wanted to know,” he said, “was ‘do we have to pay these damn bills?’”

The problem with a crash course in the woes of WPPSS is that it defies a “this happened because of this” logic and instead becomes the hopeless retracing of a convoluted ant’s journey that soon frustrates one who tries to make sense out of it.

The same year (1976) Ellensburg was prodded into signing up for the two plants, Portland General Electric Co. finished the Trojan nuclear plant north of Portland. Trojan can generate 1130 megawatts of electricity, and it was built at a cost of $460 million in 5.5 years. The two latest WPPSS plants, on the other hand, were only to be slightly larger, at 1240 and 1250 megawatts respectively. In the same amount of time it took to build Trojan, $2.25 billion had been borrowed and spent on WPPSS 4 & 5; neither plant was as much as 25 percent complete: and the latest estimates of their cost upon completion (including financing costs during construction) ranged from $12.5 billion to over $23 billion depending on when the plants were finished.

The reasons why it would have cost WPPSS more money to finish the two nuclear plants than it would have cost for two dozen Trojans built in the early ‘70s do not lend themselves well to capsule summaries. They are so hopelessly intertwined as to be mind-boggling. And while there is ample evidence that the Supply System’s problems were largely of its own making, the very goals WPPSS could not handle were anything but its own. Those who pushed hardest for WPPSS to do the region a favor and take on plants 4 & 5 were BPA and the region’s aluminum industry. Yet, in the end, neither had any liability in the plants’ failure. Ellensburg and the 87 other utilities and co-ops who—after ominous warnings from Bonneville about power shortages—signed on to the projects so they could be financed with tax-exempt municipal bonds, are simply left holding the bag.

Now here comes the next warp in the tunnel of mirrors: The very reason Ellensburg jumped on the bandwagon has vanished without a trace. The ominous forecasts were wrong, very wrong. Now Bonneville spokesmen are saying the region should enjoy adequate electricity supply through the end of the decade—without WPPSS 4 & 5. Even had they been finished on time, on budget, and with red, white and blue bunting on the cooling towers, the plants would not have been needed.

Amid the political, economic, and technological mirages along the road with WPPSS there would just happen to be two indelible facts that, five years later, would bring the wagon back to Pearl Street. One was that the billions of dollars spent on the plants turned out to have been real money. The other was a section of the WPPSS 4 & 5 “Participants Agreement” known as the “hell or high water” clause. It states, in part:

The Participant shall make the payments to be made to the Supply System under this agreement whether or not any of the Projects are completed, operable, (etc.)

It means that regardless of what happened with the two nuclear plants, the debs would be paid by the 88 participants. The clause was essential. It was the security for the billions in bond debt sold, without which no bonds would have been sold and no work started on WPPSS 4 & 5. Money to pay off bondholders would come from the participants who had to adjust rates to meet their share of the debt—to charge it to their customers no matter what happened short of the Second Coming.

The City of Ellensburg has started doing just that. The more than $1.1 million per year it must raise is a sum greater than that budgeted in 1982 for city police and fire departments combined

To the Irate Ratepayers the “hell or high water” clause provokes the sudden realization that one has been conned. They see themselves being forcibly sold something they didn’t need and aren’t getting anyway. They see people who invested in WPPSS bonds at some of the highest interest rates in history for tax-exempt securities and won’t lose a cent. They see the only losers are in places like Ellensburg where a handful of part-time elected officials voted as full-time experts told them they should.

“My argument with the city council,” says Ms. McMillen, “is here that were being leaned on by these so-called experts mumbling jibberish about forecasts, megawatts and so forth and they just nodded their heads and signed on the dotted line. They didn’t even read the contracts.

“One of the first places I looked when I started looking into this was the Participants Agreement. I’d heard about the ‘hell or high water’ clause and I was willing to maybe forgive if I saw it was written in vague legalese. It’s in the King’s English. I wouldn’t have bought this knife (the big one at work on the celery) under an arrangement like that.”

Now here comes the next warp in the tunnel of mirrors: The very reason Ellensburg jumped on the bandwagon has vanished without a trace. The ominous forecasts were wrong, very wrong. Now Bonneville spokesmen are saying the region should enjoy adequate electricity supply through the end of the decade—without WPPSS 4 & 5. Even had they been finished on time, on budget, and with red, white and blue bunting on the cooling towers, the plants would not have been needed.

To say the issue has become emotional puts it lightly. There was, for example, that evening several weeks back when McMillen and a handful of accomplices wanted to ensure their voices were heard at a meeting with the city council at Hertz Music Hall on the CWU campus. They did so by arriving early at the hall, pulling a table up on stage next to the city council dais, hooking up their own portable address system, and steadfastly refusing the mayor’s orders to disperse. This in a community where civil disobedience was generally thought to be limited to those few tourists who fail to wear Western garb during Rodeo Week. That they were able to get away with it was due to the fact that most of the over 300 people who witnessed it were supporters.

The fact is the costs of the WPPSS surcharge could not have come to Ellensburg at a worse time. Unemployment here is at 18 percent and in the past two years Ellensburg has lost its second largest employer, the Schaake Packing Co. with its 300 jobs, and seen cutbacks at CWU, its largest employer. Then, in May, CWU President Daniel Garrity said several more faculty members would be laid off because of the $225,000 the surcharge would add to the school’s annual electricity bill.

“Most of what’s holding it (the local rebellion) together is the poor economic condition of the town,” says Ned Penitsch, who lives in Ellensburg with his wife and commutes to work as a trucking company manager in nearby Yakima. “We’re not saying the surcharge will be disastrous but when it comes when we’re all being asked to take cuts in salary an increase like this is going to be felt.”

The revolt in Ellensburg has already gone beyond the talk phase. The Irate Ratepayers filed suit against WPPSS and the city in May seeking relief from the surcharge and several have notified the city of their refusal to pay it. How many is in dispute. City Manager Robert Walker said that although no one at City Hall is keeping a running count, he estimated about 50 such notices had been received by early June. The Irate Ratepayers insist the number is in the hundreds and claim it will soon become several hundred.

The Hell or High Water clause was essential. It was the security for the billions in bond debt sold, without which no bonds would have been sold and no work started on WPPSS 4 & 5. Money to pay off bondholders would come from the participants who had to adjust rates to meet their share of the debt—to charge it to their customers no matter what happened short of the Second Coming. The City of Ellensburg has started doing just that. The more than $1.1 million per year it must raise is a sum greater than that budgeted in 1982 for city police and fire departments combined.

The wrenching effect of the surcharge on Ellensburg has brought a number of strange twists. One of them is that the most eloquent advocate of the ratepayer revolt in Ellensburg is on the city council and is paying her electricity bills. Her name is Irene Rinehart, and if Ellensburg escapes its debt to WPPSS 4 & 5 the ratepayers would be justified in using some of the savings to erect a monument to Mrs. Rinehart next to the community gazebo at Fifth & Pearl.

Mrs. Rinehart has been a fixture on the city council since 1967. She has a Ph.D. in English, has taught the subject at several universities, and makes good use of the language every other Monday night. from the time it finishes the pledge of allegiance until it adjourns, the Ellensburg council does its business to the tempo of the articulate, verbal muzak of Irene Rinehart. She approaches every issue the same—with a stack of homework and a long list of questions. No question is too simple to risk asking and no matter on the agenda too insignificant for her to be satisfied to understand. If that trait had been shared by the WPPSS board of directors the Northwest might have been spared an enormous tragedy. Had it been shared by a few more members of the Ellensburg council in 1976, at least one town might have been spared.

The other member of the council who voted with Rinehart against joining WPPSS 4 & 5 was Tom Lineham. Lineham’s account of the fateful meeting, recorded in his journal the morning after the vote, reads today like an omen. He complained that the contract committed Ellensburg to a project with “which we had really no idea as to its economic impact to our city.” In lieu of the long-range effects of the pact, Lineham wrote, it would have only been reasonable to consider other information and “at least” become more familiar with the information they were given.

The official record of that meeting shows Rinehart and Lineham dissenting because “they felt they were not sufficiently informed and wanted more time for study. The minutes show that a lone citizen spoke and “commented that Councilwoman Rinehart’s concern was very valid and of concern to him.”

Today, Lineham is the resident angry ratepayer on the city council. He is leading by example and refusing to pay the surcharge on his own utility bill, something that has bred considerable friction between him and the rest of the council, particularly Nickel, who says the two aren’t talking to each other. Lineham, the city’s first representative on the WPPSS board after the 1976 vote, has been telling his constituents that bold action is necessary to reform a system that he says has betrayed the pubic trust and in which “vested interest still rules.”

Mrs. Rinehart, on the other hand, voted for the surcharge, but insisted the ordinance ordering its collection cite the WPPSS 4&5 debt as an “alleged” obligation. The city has hired a Seattle bond attorney (paid with funds collected via the surcharge) who’s been instructed, among other things, to investigate a legal challenge that might free the city from its obligations to WPPSS 4 & 5.

Although she concedes that Ellensburg cannot plead illiteracy and ignorance on behalf of its council for having put their signatures to the “hell or high water” clause in the first place, Mrs. Rinehart believes, like the Irate Ratepayers, that the city should not be bound to it.

“I suspect this is a kind of blackmail,” she says. “I would go so far as to say it’s uncivilized, because it doesn’t recognize the interdependence and mutual obligation that is the basis for society. I’m exactly where I was in 1976.”

Six years before he got a call from Belinda McMillen, Dr. Ken Hammond got a call from Irene Rinehart. She had heard of Hammond’s public warnings about the folly of WPPSS 4&5 and, as part of her preparation for a vote on the issue, sought his views. A well-credentialed scholar with two file drawers in his CWU office stuffed with his research on Northwest energy planning, Hammond was then accused of being “anti-development” for his views.

The year before WPPSS and Bonneville officials traveled the Northwest to recruit public utilities for WPPSS 4&5, Hammond traveled the region to find out what ideas the power planners themselves had about the region’s energy future. What he found was a constellation of groupthink.

“There was a general assumption that they could not go wrong by producing additional electricity,” he says.

“As it was, no council member admitted that he or she really had studied the documents…and something which would affect Ellensburg when several members of this council were six feet under, took a mere five minutes.” —Diary of Ellensburg city councilman Thomas J. Lineham, May 18, 1976.

Hammond did his own work. He took all the major premises that the power planners who lined up solidly behind WPPSS 4&5 were using and picked each of them apart. Without even considering the safety issue of nuclear power, for example, he saw a clear trend indicating that the costs of the technology were increasing dramatically. But, more important, he found that forecasts of demand for electricity were grossly overstated because they were based almost entirely on growth trends of the region’s economic boom years—growth not at all likely to repeat itself. He was right, too right.

“It’s far worse than I ever thought it would be,” he says of the economic costs to Ellensburg of the mistake. “And I thought it would be bad.”

Regardless of how bad it gets, people here are going to pay their electricity bills—the experts have said so. After all, even with the much-loathed surcharge in Ellensburg, in New York they’re paying three times more; in Chicago and Los Angeles twice as much; and, in Atlanta and Washington D.C people are paying almost 50 percent more for their electricity. It’s still a good deal here.

So much a good deal they’ll actually come up with new ways to use it—the experts have said that too. As recently as November 1980, WPPSS’ official statement to bondholders include a forecast showing that although rates would quadruple during the next decade, by 1990 people in Ellensburg would be using 7 percent more electricity per customer. (The fine print said it was based on past history.) That’s what the experts told the bond buyers they were banking on, namely that there was a lot that could go wrong with nuclear power in particular and the world in general and people in places like Ellensburg would still pay their bills.

So far they’re right. Most people in places like Ellensburg are paying their bills. But some of them ask unsettling questions. Like Art Borgens, the retired hamburger stand operator who was doing brisk business selling “I’m Irate” buttons outside Hertz Hall the night his comrades stole the stage inside.

“The thing I detest about the whole thing is that we are buying a whole bagful of mistakes,” he said. “Do you really want to conscientiously support that with your money? I mean, can you support it? And if you do, then aren’t you part of the problem?”

Belinda McMillen and her neighbors may not change the system but they’ve already dispelled the naive assumption that once grew like moss at the foundation of energy planning in the Northwest: that the customer is mute. If they do any more than that then the experts and the people holding WPPSS bounds will have seen one mistake too many.

—tjc

Black & white photos courtesy of the Ellensburg Daily Record

Photo of the Davidson Building via Wikimedia images

That fiasco ended my father's nuclear fuel fabrication career as Exxon Nuclear sold the Horn Rapids Rd plant in Richland, WA to Siemens.