Rough-legged hawk, at perch in the scablands of western Whitman County

A splendid collision of two great stories

One of the challenges in sharing The Preposterous Spokane Flood story this coming Friday (here, if you missed it, is the invitation) is the problem of scale.

When the Spokane River is swollen with snowmelt in the spring it’s entertaining to take visitors to the footbridge at Riverfront Park where you can feel and hear the power of the water at its peak annual flow. You have to yell to be heard. But even the roaring Spokane is a thimble to the great floods that excavated and overflowed the Spokane valley near the end of the Pleistocene epoch (2.58 million to 11,700 years ago).

How to explain this?

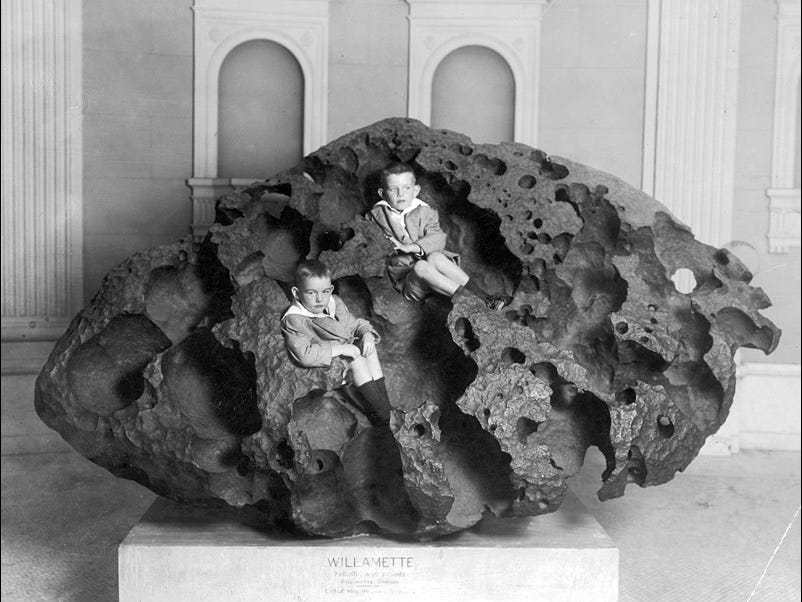

“Tomanowos,” (aka The Willamette meteorite) photographed at the American Natural History Museum in New York City, 1911 (photo courtesy of Wikimedia images)

Maybe the best way is to double down on the preposterous, because there was a day (let’s say 17,000 years ago) when two great Pacific Northwest stories converged in a remarkable astro-geological-climatological coincidence.

The first story concerns a celestial object we know (now) was entrained in the massive Purcell trench glacier that groaned and grinded southward, into what is now northern Idaho, during the most recent ice age. The exotic passenger was a 17-ton mass of pitted iron and nickel (the stuff of exploding stars)—the largest known meteorite to have landed in North America. The second story is that of the massive outburst floods from glacial Lake Missoula that occurred several times during the late Pleistocence. The floods occurred each time a massive ice dam—the leading tip of the Purcell trench glacier—exploded under the enormous pressure of glacial Lake Missoula, the massive body of water created by the ice dam, near present day Sandpoint, Idaho.

Because most (though not all) of the outwash from glacial Lake Missoula came through the Spokane Valley on its way to the Pacific Ocean, it is more-likely-than-not that Tomanowos (the name given the meteorite by Native Americans) surfed right through Spokane on its journey toward the sea. It didn’t quite reach the ocean because, near present-day Portland, much of the floodwaters were diverted southward, into the Willamette valley. This is where Tomanowos came to rest, in woods near what is now the small city of West Linn in Clackamas County. (One of Spokane’s finest story-tellers, author Jack Nisbet, has a chapter in his 2015 book Ancient Places about the discovery of the meteorite and how it wound up at the American Natural History Museum in New York, where it presently resides.)

I use the word “surfed” purposefully because it forces us to imagine the size of the iceberg that would have been necessary to float the 17-ton meteorite all the way from Sandpoint to Portland. But that is what happened—there is no meteor crater where Tomanowos was found. As Nisbet reports in Ancient Places, an Oregon high school teacher, Jack Pugh, decided, in 1986, to make a careful search of the underbrush at the site where Tomanowos had been removed in 1903. There Pugh found several boulder-size chunks of granodiorite—an igneous rock that is not native to the Willamette Valley but which is common in the Purcell trench of the Canadian Rockies. The granitic boulders had traveled in the same iceberg as the meteorite.

It’s a shame that neither J Harlen Bretz nor Thomas Large lived long enough to know this part of the story. Bretz, of course, is the famous geologist who put his name to the 1923 journal article proposing the great flood theory of the scablands. His paper rocked the American geological establishment which, at the time, was highly skeptical of theories that attributed widescale changes to catastrophic events. Thomas Large was the most energetic personality in a cadre of Spokane-area science teachers who suspected—correctly—that a great flood had been involved in creating the deeply gouged and gnarled landscape around Spokane. Large—who taught science at Spokane’s Lewis & Clark high school—took the lead in persuading Bretz to come to Spokane and do the meticulous field work that supported the now-famous 1923 paper correctly espousing the great flood theory. Large and the Spokane science teachers playfully referred to the theory as the “Outrageous Hypothesis.” And time would prove them and Bretz correct.

Even before Bretz arrived in Spokane in 1922 he was intrigued by what geologists refer to as “erratics”—large rocks whose composition does not comport with the local bedrock or known outcrops. Erratics are typically features of glaciation—where ice sheets pluck chunks of rocks from outcrops they bulldoze through and then drop them miles away when the ice ultimately melts. The riddle in the lower Columbia basin is there are enormous erratics of granitic and metamorphic rocks left stranded on hillsides far from where the Cordilleran glaciers had advanced. How did they get there? The answer, of course, is the great floods—and in this story Tomowanos is the most exotic of the erratics. It’s fun to imagine how Bretz and Large would have responded to Jack Pugh’s survey in 1986, essentially proving that Tomowanos (aka The Willamette meteorite) had arrived in Oregon via the ice age floods.

Again—as Jack Nisbet explains in Ancient Places—it is more likely than not that this enormous meteorite came right through what is now Spokane during the late Pleistocene. But it’s not as though it would have tumbled through what is now Riverfront Park. Rather, it would have been 1,000 feet overhead, riding in an iceberg, floating atop the floodwaters, and traveling at freeway speed.

A chance to hear geologist Chad Pritchard

One of my mentors on Spokane-area geology (and Northwest geology in general) is Chad Pritchard of Eastern Washington University’s Geosciences Department. He was a great help, for example, when I researched and wrote the Beneath Our Feet cover story for the Pacific Northwest Inlander last April. Aside from his technical research Chad is a co-author of Washington Rocks, a superb, general-interest book on Washington state geology.

EWU Geosciences professor Chad Pritchard

Because of his knowledge and extensive field work, Chad is also a key player in the current saga of the serious “forever chemicals” groundwater contamination on the West Plains of Spokane County. He is now the lead investigator in a state-funded “Transport & Fate” study to try to determine how the PFAS “forever chemicals” in fire-fighting foams used at both Fairchild Air Force Base and Spokane International Airport are infiltrating the very complex aquifer system(s), between Interstate-90 and the Spokane River in western Spokane County.

You can follow my investigation of this important and complex story here at The Daily Rhubarb and at the Rhubarb Skies website.

Chad will be giving a presentation on West Plains groundwater situation and the scope and timeline on the study he is heading up tomorrow night (Monday, Jan. 29th) at The HUB in Airway Heights. The session, hosted by the West Plains Water Coalition, is free and open to the public. It starts at 7 p.m. (The HUB is located at 12703 W 14th St., which is just off Highway 2, about a football field-length east of the Yokes Fresh Market at Highway 2 and King Street in Airway Heights.)

—tjc