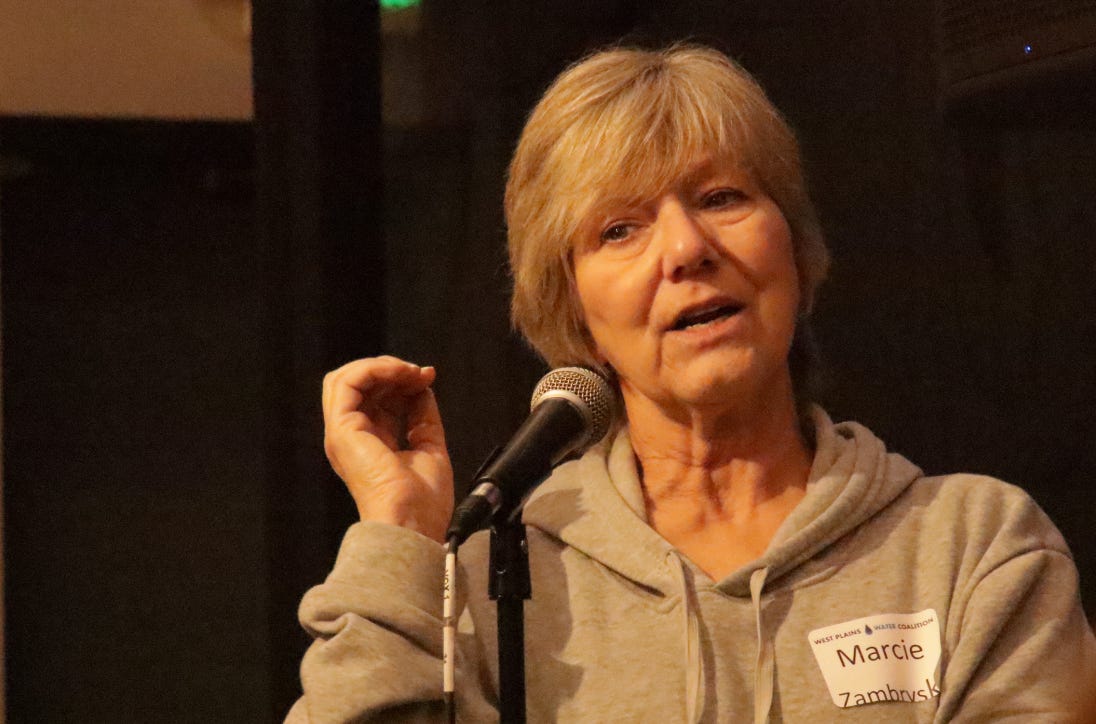

Marcie Zambryski, a founding member of the West Plains Water Coalition at a WPWC meeting in December

How a grassroots citizens movement is changing the maps of Spokane’s West Plains

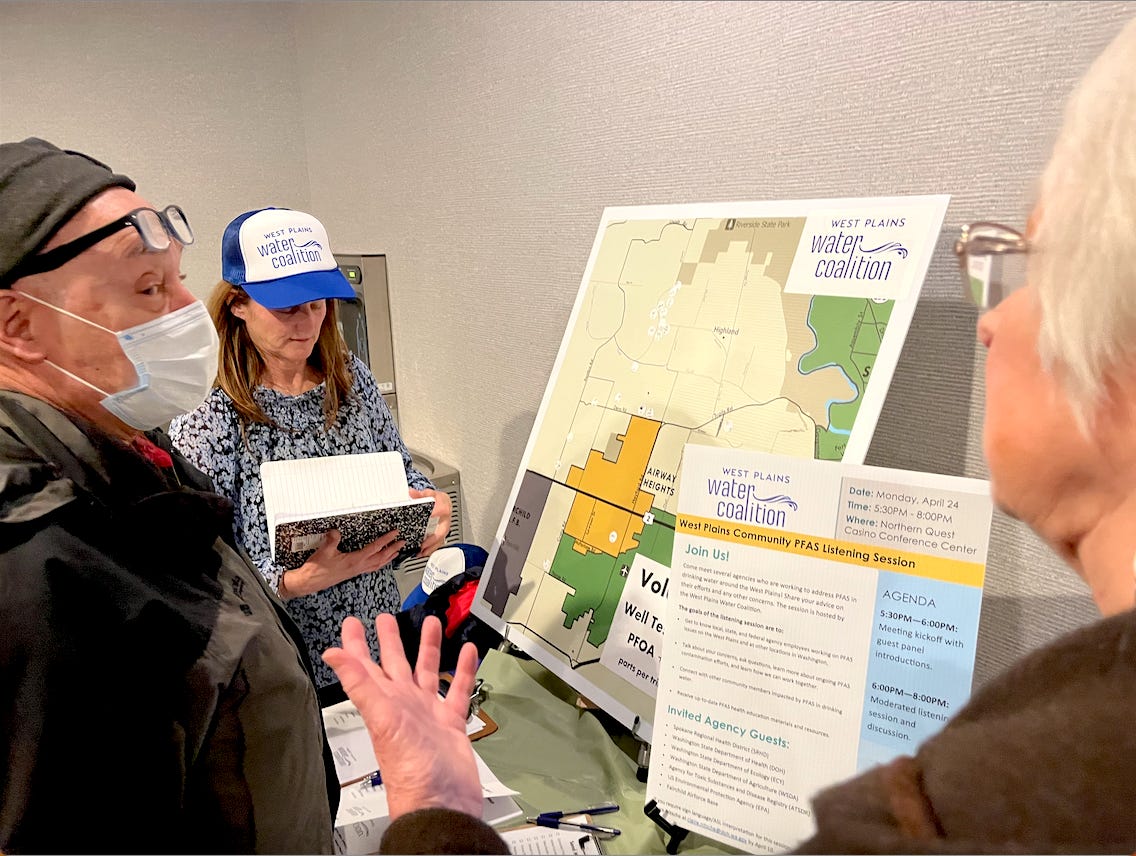

One of oddest public meetings I’ve ever walked into was in a ballroom at the Northern Quest Resort and Casino nine months ago.

This was on a Monday evening in April. It was a “listening session” cobbled together by the nascent West Plains Water Coalition and facilitated by the state’s Department of Health. The subject was tainted water and the mere fact that such a large room was necessary for the expected attendees spoke volumes. Though it had been six years since the West Plains community learned that fire-fighting foam used at nearby Fairchild Air Force Base had contaminated much of the area’s drinking water with toxic “forever chemicals,” there were growing fears that people were still vulnerable—physically and financially—to the as-yet unmapped spread of unsafe groundwater.

I took a seat in the front row from where I could read faces in either direction. There were deeply engaged, fearful and frustrated people listening in the rows of chairs behind me. In front of me was a single line of chairs turned toward the audience. In the chairs were local, state, and federal officials whose faces were grim and whose body language also spoke to their discomfort.

The dangers the presenters could speak to were quite different than the hazard that could not be. The open culprit were variants of PFAS—per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances—that for decades were ingredients in aviation fire-fighting foam. In short, PFAS consumption can wreak havoc with the human endocrine system. It is a fiendish substance.

But the unspeakable problem is a relatively small but influential cadre of political and economic players still trying to shield the Spokane International Airport from what turns out to be its own PFAS problem. As detailed in my recent article, Al French and the “Forever Chemicals,” the evidence is compelling that top SIA officers have known since 2017 about significant levels of PFAS in the airport’s groundwater. It’s also undisputed they made no effort to share that information with neighboring property owners and environmental and public agencies including those represented in the chairs at the casino ballroom last spring.

In short, a good faith effort by state and county environmental and health officials to be proactive and protective of public health was stymied by the county’s most powerful elected commissioner. The quiet effort to downplay the PFAS problem and shield the airport wasn’t widely known last April. But neither was it a secret. People can smell power, and the abuse of power has a scent as distinct as rotten eggs.

The line up at the April 24th “listening session” at the Northern Quest Casino

The problem at the airport, is still the problem at the airport

This piece you’re reading is, for the most part, a good news story. I could have written it Thursday morning. But Thursday afternoon was a deadline of another sort—the end of a 60-day extension period the airport had been granted late last year by the state Department of Ecology to reach a settlement to start cleaning up the PFAS contamination at the airport. There was no public announcement, Thursday, because no settlement has been reached. Instead—according to Ecology public involvement coordinator Erika Beresovoy—SIA has requested an additional extension.

As I reported last September, SIA’s response to Ecology’s efforts to bring the airport into compliance with the state’s toxic waste law were met with a defiant letter from the Washington, D.C.-based law firm the airport had contracted with. Under the circumstances—SIA getting busted for not disclosing a toxic chemical release—it is a breath-taking piece of work, especially considering that the cleanup process at the airport would be well underway by now had SIA disclosed its monitoring results, rather than suppressing them for several years.

By the time I spoke with Beresovoy Friday afternoon she said a draft response from Ecology’s SIA site manager Jeremy Schmidt was already on its way to Ecology headquarters in Lacey for approval. She did not rule out an additional extension but reiterated Ecology’s earlier expressed resolve to move swiftly to put a sound cleanup plan in place. Under state law, she added, “when we no longer feel that the other party is negotiating in good faith” the agency has the purview to proceed with an enforcement order rather than a negotiated agreement. Beresovoy said she expects Ecology’s response to be made public in the coming week.

The Blue map, and the Red map

On the left, in blue, the area west of Hayford Road in which the Air Force monitors wells for PFAS and provides assistance where warranted. On the right, in red, is the area east of Hayford Road beyond reach of the Air Force’s assistance. It is in this area where EPA and the Washington Department of Ecology will soon provide free well testing for PFAS, with the prospect of additional help to come.

One of the signatures of the West Plains PFAS problem is the dearth of elected government leadership and accountability. When the Seattle Times published an exposé on West Plains PFAS last October, it wasn’t only airport CEO Larry Krauter who refused interview requests. It was also commissioner French and then-Spokane Mayor Nadine Woodward who brushed off the Times’s journalists—despite the fact that SIA is a joint venture of the city and the county.

In a narrow sense, Spokane’s PFAS cover-up wouldn’t seem to be the Department of Ecology’s problem. But in the real world of how communities respond to news of toxic substance exposures, emotions are understandably on edge. Fiascos like the SIA cover-up of its well data can inflame the entire process of investigating and resolving complex public health challenges like that on the West Plains. Trust is tenuous, and perishable.

Near the top of the list of the problems the Department of Ecology inherited when it moved to take action against SIA last year, is the Hayford Road boundary. While the Air Force acknowledged it had a big PFAS problem at and around Fairchild Air Force Base in 2017, it’s response plan (under which it delivers bottled water to West Plains residents and offers on-site systems with granulated activated charcoal filtration) comes with a perimeter.

Mark Loucks is the environmental restoration specialist who guides the FAFB remediation. At a public meeting last week, Loucks defended the boundary line at Hayford Road—a main artery on the West Plains that runs north/south and just to the east of the Northern Quest Casino. Simply put, Loucks explained that a so-called “paleochannel” runs roughly parallel to Hayford Road and “we do not have any evidence so far to say that that, you know, [the PFAS contamination] goes beyond that [Hayford Road].”

In an email he wrote last November to a concerned well water user east of Hayford Road, Loucks was more specific and pointed to the Spokane airport: “The data we have collected so far indicates that PFAS contamination from Fairchild sources does not go east of Hayford Rd. We also know that a second paleochannel controls flow direction from the Spokane Airport and heads north into the area where you currently reside. The Spokane Airport also is a user of AFFF and has trained with it for decades and there are at least two known source areas that have likely impacted groundwater with PFAS constituents that could be in drinking water north of the Airport.”

The practical reality is if you live west of Hayford and have PFAS in your well water at greater than 70 parts per trillion (an action level based on EPA’s interim safe drinking water guidance) you can get help from the Air Force. East of Hayford and you’re out of luck. Until now.

In a stunning move two weeks ago, Ecology and EPA officials essentially swooped into a regularly scheduled public meeting in Airway Heights (hosted by the West Plains Water Coalition) to announce they were moving swiftly to address the Hayford Road conundrum. They described a plan whereby private well testing for PFAS will be made available, at federal expense, to residents east of Hayford Road. The initiative was announced by Ecology’s Beresovoy and Laura Knudsen, an EPA Region X community involvement coordinator. (Ecology has not yet activated its free well-test enrollment application but when it does it will be accessible at this webpage.

The Great Northern school house north of Spokane International Airport, where PFAS contamination forced installation of an expensive treatment system.

I spoke late last week with Beth Sheldrake a regional EPA branch chief in the “Superfund” emergency response program whom, I’d learned, was instrumental in formulating the initiative along with (among others) Beresovoy and Ecology’s Bri Brinkman, a co-site manager in the Spokane Airport enforcement action. It’s a big deal. In a stroke, the collaboration between Ecology and EPA has leapt months—if not years—ahead. It doesn’t undo the years of delay caused by the airport’s coverup, but it does limit the harm currently being caused by delays created by the airport’s intransigence and attempts to thwart or further delay compliance with the state’s ‘polluter pays’ toxic waste cleanup law.

Water coalition volunteers at an educational display on the PFAS problem at a meeting last spring

A typical process under state law would be to physically locate the source(s) of the airport’s groundwater contamination and track the plumes outward from the source. If the plumes are found to contaminate off-site drinking water then the polluter (in this case the airport) would be liable to pay for the remedy. From a dead start, though, that could take months and we’re likely months away from actual field work at the airport.

But the newly announced plan to offer the free well testing will be federally-funded via EPA’s “Superfund” response process, and largely independent of the SIA enforcement action by Ecology. It does, of course, beg the question of what follows if and when tests confirm the presence of PFAS above action levels. (Currently, state action levels for PFAS are significantly lower than the interim federal advisory of 70 parts per trillion). To reach some form of parity with the Air Force’s program, well water users east of Hayford Road would also have to be eligible for financial assistance to treat PFAS contaminated water—the systems and maintenance for which can easily run into the thousands of dollars per household.

The question of how to fund and allocate assistance to those whose well water is found to contain PFAS above regulatory limits has been part of discussions for months and is certainly a topic being pushed by the West Plains Water Coalition.

“I just want to acknowledge that those conversations are happening,” Sheldrake told me. “Like you're seeing at Fairchild,” she added, “there's also a part of Superfund..where if a risk is identified that needs to be mitigated more quickly, then there are the tools within the Superfund program to do that and MTCA [Washington state’s toxics cleanup law] has a similar sort of thing.”

It’s hard to imagine that any of this would be happening without the extraordinary work of the West Plains Water Coalition, whose first unofficial meeting was a potluck in John Hancock’s living room in Deep Creek last winter.

John Hancock at a coalition meeting in Airway Heights

When I asked Hancock to reflect on the coalition’s role as a catalyst for engaging the environmental and public health entities involved in the announcement, he smiled and said it had taken some work to draw attention “to the gap in the regulatory safety net” that left private well owners like him and his neighbors vulnerable to events like the widespread PFAS contamination on the West Plains. And now, so suddenly, help is on the way.

“When I thanked the people I knew in these agencies,” he said, “several of them said this wouldn't be happening if it weren't for the pressure that you've been putting on the system to respond to what's obviously a human health story.”

I also spoke with Craig Volosing, a veteran leader with the Friends of Palisades organization that has supported the coalition since its inception. Volosing said he felt he and his organization have been vindicated by the EPA/Ecology announcement. Prior to the coalition’s formation, Volosing had been working with Eastern Washington University geologist Chad Pritchard and other groundwater experts who’d had been warning about the vulnerability of West Plains groundwater to PFAS and other hazardous chemicals.

Says Volosing: “Like [Spokane County water resource manager} Rob Lindsay said, it’s not going to go away.”

Volosing chuckled when he told me he’d felt like a member of a scouting party trying to summon attention to the problem but now, with state and federal regulators working in unison, “here comes the cavalry” with much needed resources.

Chuck Danner at his home north of Spokane International Airport

As did Volosing, Chuck Danner raised the issue of accountability for French and the others who’ve tried to sweep the West Plains PFAS problem under the proverbial rug. I met Danner as I was researching the Al French and the ‘Forever Chemicals’ story. Danner lives east of Hayford Road and has elevated levels of PFAS in his bloodstream. It was to Danner that Loucks had written the 11/21/23 email, politely informing him the Air Force wouldn’t help, and pointing a finger toward the airport.

“All of this is really encouraging,” Danner said about the Ecology/EPA announcement days earlier, about it’s free well-testing program. But he also told me he was ambivalent about taxpayers having to pick up the tab while those responsible were not experiencing consequences.

I also called Marcie Zambryski, a neighbor of Hancock’s in the Deep Creek area who lost both her husband and mother to cancer before learning the well water they’d been drinking for years was contaminated with PFAS. She is one of the founding members of the coalition, and it was her taking notes on butcher paper at the meeting in the casino ballroom back in April.

Though she has been encouraged by the growth and progress the coalition has made in the past year she still carries the grief of losing her husband and mother. She’s also frustrated with the terms of a contract the Air Force has offered her that would ostensibly provide her with treated water but with conditions that—as she reads them—would not only not make her whole but put her finances and property value at risk. She had gone to the Air Force’s public meeting last week and discussed the contract with Loucks. It did not go well. It was reminder that there is no instant or inexpensive fix to the changes she and others have had to confront as the contamination has spread.

I complimented her on her hard work for the coalition.

“Because we have no other choice,” she quickly answered.

It is, after all, a forever chemical.

—tjc

Editor’s note, Rhubarb Salon is the “free” channel for The Daily Rhubarb.

Reporting and commentary on the West Plains PFAS issue is a free public service at Rhubarb Salon, but please consider donating to support the project, or via a paid subscription to The Daily Rhubarb at the above link.

Great work, Tim. I was at the RAB meeting and open house last week. I'm sorry I didn't get to meet you. Next time.