Friday's featured photo, and billions of other clues to the catastrophe that delivers Spokane's water

October 13, 2023

Fist of basalt atop ancient cobbles delivered to Spokane by the Ice Floods, roughly 17,000 years ago

One of the highlighted paragraphs in my pile of research on the Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie aquifer is in a thick 2005 report by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). It’s a dry observation about water—more specifically about the immense pile of saturated cobbles delivered to the Spokane area by glaciers and mind-boggling floods at the end of the Wisconsinian Ice Age, roughly 17,000 years ago. In geologic time, this is barely yesterday.

In dispassionate, technical prose the report tries to describe the depth of an illusion—the flatness of the Spokane Valley.

You can visualize this by driving (or remembering your last drive) on Interstate-90 between Post Falls, Idaho and Spokane. The freeway bends, gently, to follow the Spokane River into the city but it could easily be as direct as Sprague Avenue which leaves downtown Spokane, heading east, on an 11-mile bee-line for Veradale before nudging a bit to the north to avoid Liberty Lake.

What you may not realize is that your tires are spinning above a deep, natural fill of saturated cobbles. How deep? Generally about 500 feet deep. But the paragraph from the USGS report that I’d highlighted reports on a deep well just north of Spokane where “a 780 foot well did not penetrate the full thickness of the glacial and flood deposits.” Being professional geologists the authors did not insert an emoji or exclamation mark, but I think it’s implied.*

Spokane River in the Spokane Valley, looking east toward the Idaho mountains

I began to pay closer attention to these beautiful cobbles about a decade ago on my near-daily summer swims in the Spokane River. They’re hard to miss, especially in direct sunlight because the water brings out the colors in the argillite—the ancient mud and siltstones that, along with granitic and metamorphic rocks, dominate the exposed cobbles in the river and along its banks. And that’s the story of the photo I’ve framed, above: That’s actually a fist-sized piece of relatively young basalt atop the colorful cobbles—many, if not most, of which were torn from 1.4 billion year-old Belt Basin outcrops in Idaho and Montana. This occurred in the maelstroms caused by the burstings of the Purcell Trench ice dam that blocked the Clark Fork River, creating glacial Lake Missoula. It is the massive outwash from those repeated, explosive collapses of the ice dam that carved the Spokane River gorge and deposited the countless billions of cobbles.

The cobbles of the Spokane aquifer are still vital to Spokane because the discovery of the aquifer a bit more than a century ago saved the city from the self-inflicted crisis of severely polluting its namesake river. Just in time, it was able to replace the polluted river water with crystal clean aquifer water. Although the river is much cleaner now than it was a century ago, the city still relies on the aquifer for its drinking water.

The Spokane River’s signature wild, redband trout

Finally, there is a strong connection between the aquifer and the flow in the Spokane River, especially in the dryer months between July and November. The availability of the cold and clear water is essential for my favorite swimming companions, the wild, native redband trout that are the living signature of the Spokane River.

For obvious reasons, the ancient sedimentary and metamorphic rocks in and along the riverbed are among my favorite photo subjects. Other dramatic images of the rocks are included in the following on-line galleries at my Rhubarb Skies website.

If you’re interested in purchasing a print of today’s featured photo, or one of its kin, contact me via Substack or at tjconnor56@gmail.com. Discounts apply to paid subscribers to The Daily Rhubarb.

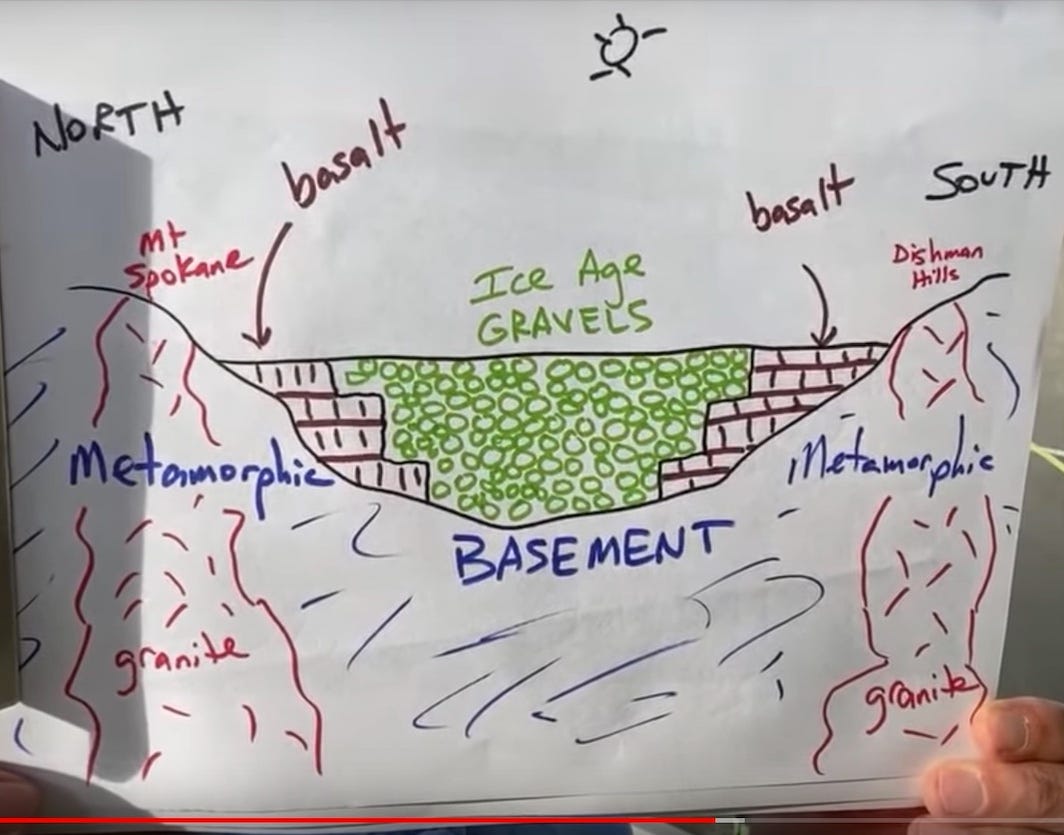

*p.s. An even better way to visualize Spokane and its geologic setting is the way Central Washington University’s Nick Zentner presented it in one of his trademark video lectures. Spokane sits in what we would call a coulee (like Grand Coulee or Moses Coulee) if only we could see it. But we don’t see it because it’s filled in with cobbles and boulders nearly two football fields deep. Here’s Nick holding his hand-drawn cross section of Spokane.

You can watch the whole lecture here.