Close Encounters with the Mirror World, Part 2

January 12, 2024

The Offramp

My introduction to conspiracies, oddly enough, came during the driver’s ed class that I took with two of my friends in high school. Our teacher was a short, greasy dude with a ponytail who wore a Chinese coin on a beaded necklace and regularly regaled us with information about the Bilderberg group, the Illuminati, FEMA—organizations supposedly orchestrating the mass murder of billions for a “new world order.” The three of us thought maybe he was opening up to us because we were smart, mature, and had been forced into adult levels of thinking by our respective traumas. However, as in the influencer culture to which my and my younger brother’s generations have now been culturally attuned, he just wanted someone to pay attention to him and listen. Despite the degree of vulnerability we felt we’d breached with this man who took hours every week to unpack his distrust of the United States Government in our presence, it turns out we weren’t special, and when two of us went to visit him a year later, he barely seemed to remember who we were.

What confused me at the time doesn’t a decade later. Conspiratorial thinking, once a fast-track to being labeled as “crazy,” has now become a legitimatized topic of discussion, at least within right wing media. It does not do this in solidarity and observance of the way that conspiracies have been continuously leveled by Western governments towards Black and Indigenous communities. This, despite the fundamental role such campaigns have had in the formation and shaping of the American government, a chapter that seldom makes it into our high school history textbooks.

The modern canon of conspiracies are instead refracted—often based on real violence enacted upon marginalized communities—and largely predicated around the perceived danger imposed on white Americans by a fantastical “elite.” Such paranoia and lazy fantasy also makes its way into the New Age and spiritual realm, an intersection regularly unpacked on the aforementioned podcast Conspirituality by hosts Matthew Remski, Derek Beres, and Julian Walker.

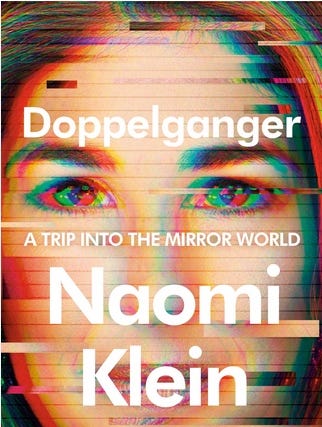

Remski and Walker are both survivors of cultic abuse, and along with Beres, the three pull on their perspectives as seasoned wellness-world inhabitants to unmask its toxic and tangled elements. In the eponymous book the three published last year, they also spend the last chapter in intimate conversation with the reader about how to lay breadcrumbs to those we’ve lost in throes of extreme belief. Klein, who never details any up-close-and-personal close bonds lost to this way of thinking, nonetheless spends the pages of her book Doppelgänger laying out the blueprints that have led to this cultural moment through the fun house mirrors of writer Naomi Wolf, a star within the right wing conspiracy ranks for whom Klein is regularly confused.

Wolf is an inhabitant of what Klein has named “the Mirror World,” where “left is right, fiction is fact, and you may not recognize even yourself.” Doppelgänger is a long-form argument that the climate of personal broadcasting/branding, technological advances, and tribalist mentalities has effectively conjured and incubated an alternative reality now freely roamed by Wolf and her new friends.

The “Mirror World” is governed by feelings and grievance, healthy skepticism gone awry, and populated predominately by white people who find solace in its propensity to deny the horrors of colonialism, white supremacy, and climate change in favor of a shared sense of security born out of grievance against the State. Conspirituality goes a step further and regularly covers how the foundation of much of this largely online realm—which utterly exploded in the wave of the pandemic—lies in the wellness, alternative health, and spiritual influence world.

It is this avenue of the Mirror World that, in many ways, has created its own economy, the trappings of which are predicated on rejecting Western medicine in favor of “higher guidance,” refracted through a kaleidoscope of gurus, yogis, psychics, and cults. It is actually through being an eternal seeker myself—someone forever reckoning the balance of inner guidance and holistic medicine with the importance, innovation, and narrow-sightedness of science—that I came upon the work of the podcasts’ hosts.

I am familiar with the fever-minded anxiety of conspiratorial thinking on a firsthand basis, and the fleeting nature by which an anxiety-riddled brain experiences the profound moments of shared empathy that never feel like enough. When you live in the Mirror World, as I periodically did in its fledgling pre-pandemic state, you spend endless amounts of time gunning for that which you think you are owed: validity, recognition, respect, redemption. You seek these things from people who will not reliably give them to you, in part because you have effectively done away with trusting most of the people in your life.

It’s never that they’re out to get you. They just haven’t woken up yet; they haven’t seen the other side of the common cultural narratives to which your suffering has exposed you. And this is why, to some degree, I will always have a bifurcated tenderness for those sucked in by extreme belief, even, people who sometimes scare me (i.e., incels). Because the pain in them doesn’t have a proper way to be felt, it gets injected and projected into all the ways one is designed, in the larger context of society, to fall short and miss out on what others so readily receive. Whether it is basic survival needs, or something more superficial that feels like survival, the promise of extreme belief is camaraderie with others and a path to fulfillment, a way past the wounding.

I believe this is the case even with many of the jackasses touting “great replacement theory”, who cannot imagine their gradual loss of societal power in the world's wealthiest nation as anything short of an utter, engineered catastrophe. This fear has calcified among white, privileged Americans who cannot imagine increased equality and diversity not actively “taking” from them what they have been socially programmed to believe they are owed. Some believe this entitlement stems from society’s recognition of their inherent worth, in denial of the golden ticket their whiteness often grants. Other, more extreme factions, cling to dominance narratives about whiteness that are as old as our nation.

These myths percolate and bloom among the wealthy (for an excellent insider's case study, check out The Atlantic’s doc “White Noise”) who use the internet as a delivery vehicle for their vitriol. The algorithm is wont to fast-track their schtick, in its various and watered-down forms, to lower socioeconomic status individuals, many in rural areas who lack racial diversity. These bubbles of whiteness, at the top and at the bottom, are bursting.

In a society that privatizes and capitalizes on even the most basic needs, the threat of scarcity hovers like a hungry ghost. So many of us are just a missed paycheck away from calamity, in a system that vehemently insists we could fix this with hard work. We may grow up uttering the words “liberty and justice for all” in our grade school classrooms during the flag pledge, but it doesn't mean anything, especially to the various groups disenfranchised and outright eradicated by our history and policies. There are a lot of people out there afraid to learn this, afraid to acknowledge that in the shoes of a different social foothold, they could easily be cast out to the wolves. It’s easier to vilify the people for whom much of society is gradually making more room, to create fantastical explanations for the rapid diversification of a country that has always hinged on immigration, rather than experience the overwhelm and anger that the truth inspires.

These myths percolate and bloom among the wealthy who use the internet as a delivery vehicle for their vitriol. The algorithm is wont to fast-track their schtick, in its various and watered-down forms, to lower socioeconomic status individuals, many in rural areas who lack racial diversity. These bubbles of whiteness, at the top and at the bottom, are bursting.

I remember a period spanning several months during which I became acutely aware of the toxic pull of oversimplification that conspiratorial thinking provides. It was accompanied by the temptation to believe that the discordant inequity and ruptures in society could be attributable to secret machinations by unknown forces. For me, it was always about feeling less powerless to confront a vision of the world so deeply shaped by trauma, inequity, and corruption, especially in the face of my own injured ego and privilege within it. This is also the case with Klein’s white rabbit—Wolf.

Prior to her ascent as an anti-vaccine activist who has been de-platformed by Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook for spreading misinformation, Naomi Wolf was known for being a feminist thinker. Granted, the scope of her feminism, Klein is quick to point out, has always been tailored to white middle class women—people, like Klein, who reflected Wolf’s own place in society in the early aughts.

Wolf wrote her seminal 1990 work, The Beauty Myth, while studying as a Rhodes Scholar at the University of Oxford. As Liza Featherstone writes in The New Republic, “It made feminists out of many of my contemporaries and helped inspire the feminist Third Wave, which included the Lesbian Avengers, abortion rights organizing, Take Back the Night marches, ‘pro-sex’ feminism, and much more.” The cultural impact of this book propelled Wolf into the throes of the “liberal elite” that she now disparages regularly. Klein, in Doppelgänger, excellently tracks the backwards spiral that inexorably landed Wolf as a regular in the insurrection den otherwise known as Steve Bannon’s War Room.

“I could offer a kind of equation for leftists and liberals crossing over to the authoritarian right,” Klein writes of this trajectory, “that goes something like: Narcissism(Grandiosity) + Social media addiction + Midlife crisis ÷ Public shaming = Right-wing meltdown.”

In reading Klein’s book, I often found myself in visceral recognition of the contradictions posed by Wolf. Concerns about being cavalier with evidence and research—a trait that first landed Wolf in public hot water (Klein sees this flaw as the loose Jenga block that destroyed Wolf’s tower of influence)—took me in the opposite direction. Instead of digging my heels in to defend the beliefs grasped in my knee-jerk reactions to a claustrophobically dysmorphic world, I took a different path, and have spent the better part of the last seven years learning how to be a better researcher, a more intersectional scholar, a more well-informed evangelist of the better world I believe is possible. Unlike Wolf, I have had the advantage of my young age and lack of relevance for open space into which I could grow.

For many other young people, the attention economy does not afford room for such dissonance, both personally and publicly. We live in an age where live-streaming allows public access to the most intimate crevices of a person’s life, and although Klein chronicles her journey as a middle-aged adult in this digital landscape, I think often of members of my own age group, the generations below me, and the consequences of such exposure.

I cringed my way through the recent (and truly excellent) Max documentary, Love Has Won, about the titular cult, feeling a sick recognition of the leader, Amy Carlson (referred to as “Mother God” by her followers) and her voyage into the online spiritual world. I spent much time on similar message boards, rife with “angel numbers,” astrological explainers, and phone psychics when I was in my late teens and early twenties. The arc of the cult, as the documentary details, is full of disturbing material. But even amidst the meth use and Carlson’s mummified corpse, what really got under my skin was the unflinching gaze of two of its members, Lauryn “Aurora” Suarez and Ashley “Hope” Peluso into the camera.

Both Suarez and Peluso are conventionally attractive, young American women who easily blend into the whitewash of the spiritual-influencer landscape. Yet within a minute of hearing them speak, it becomes clear that the degree to which they’ve exited broader reality puts them farther out into space than most.

Yes, there are familiar elements, such as mentions of “the cabal” (a reference to evil, world-controlling powerful figures commonly mentioned in conspiracy rhetoric), a reverence for Trump, and extreme avoidance of and vitriol towards Western medicine. But the entire cult revolved around Carlson (and her “Father God" boyfriends’) mercurial pronouncement of reality, which changed daily and went off-book into absurdity at a feverish pace. As the story of the doc goes, while Carlson slowly drank herself to death waiting to ascend into the fifth dimension, Suarez and Peluso endlessly held livestreams where they hawked “wellness” products they’d assembled in the cult’s Colorado compound. These included debunked substances like colloidal silver (taken to such a regular degree by Carlson that her skin turned gray), crystals, and jewelry, and art designed to “shift your frequency.”

The director noted in a recent interview that the individuals who found themselves following Carlson and consuming her group’s online presence were usually people who had undergone trauma within the American medical system and were seeking other avenues. One such member describes a bout of mysterious illness that put her in a coma for ten days. When she woke up, she had half a million dollars in medical debt, which in her words “puts you in a black hole you can’t see light out of.” At least, until she found Carlson.

Viewing the three-part Love has Won series would often bring me to “there but for the grace go I” moments. My only life-line to reject the chatter of the Mirror World, especially at the onset of Covid, has been the grounding in science and messy human reality that was afforded me as the child of a psychologist and a reporter. For all of the other fringe-y hobbies, art projects and conversations I’ve participated in throughout my life, I also was the only fourth grader in my class reading Michael Moore’s Dude, Where’s My Country?

I’m lucky in that my encounters with liminal spaces have always had a built-in umbilical cord back to a polluted planet earth populated by flawed people, even if there have been periods where I’ve disdained that tether. What I no longer take for granted is the insight—curated by growing up attuned to the world’s extreme dysfunction—that has prevented me from being indoctrinated and exploited in the way that so many seekers are.

—afc

(illustrations by Audrey)

Part 3, Destination Coexistence, Sunday, Jan. 14