A Memorial Day postcard, with a salute to my father, and the great uncles I never met

May 27, 2024

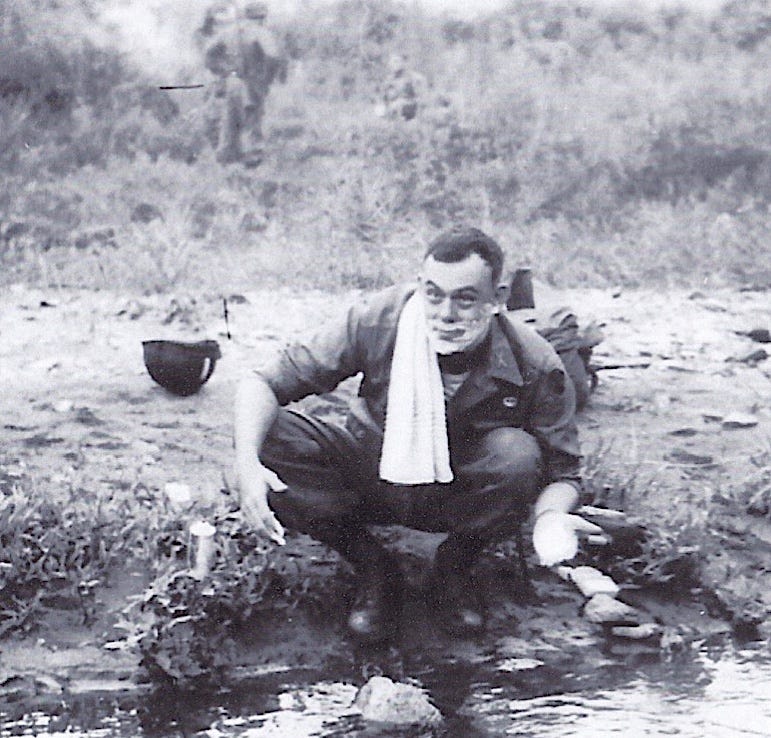

My father, Don, as a 2nd lieutenant, shaving creek side in Korea, 1956

How to fly a flag…

I received my patriotism, by osmosis, from my father. It wasn’t easy. The world of my youth was quite different from that of his.

Mine was in color. His was in black & white. He was so moved by the sacrifice of his uncles in WWII that he joined ROTC in high school and was off in Korea when I was born at Hanford in late 1956. I was one of the last teenagers to get a draft card for Vietnam but the war ended before my number came up, and I was not summoned. Thank God.

By then, in the mid-70s, the world was in color.

Color was the cultural morphine to put the horrors of WWII behind us—from Pearl Harbor, to Dresden, to Auschwitz, to Hiroshima & Nagasaki. In my mind it ended when Alfred Eisenstaedt’s camera captured that sweeping, black & white kiss that a sailor, George Mendonsa planted on a dental assistant he’d never met before, in Times Square on V-J Day, five days after Nagasaki.

It was all of a piece, a piece that for us baby-boomers was put in a time capsule. Necessary but horrible. Let’s move on—to the Camelot of the Kennedys, rock & roll, Saturday Night Live, American Graffiti…quick. It didn’t always work out well. We overdosed on just about everything. But the raw energy was there, eventually bottled in Billy Joel’s We Didn’t Start the Fire with its frantic, self-absolution.

Because I grew up and went to high school overseas, I didn’t have a well-resolved impression of American culture until I arrived as a college student in 1977. It was baffling to me. After a couple years, I’d come to the conclusion that America was a drunken cow and pretty much said so when I was invited to give a brief speech at the Edward R. Murrow symposium at Wazzu in 1979. (I haven’t been invited back. But let’s not digress).

It struck me that there was an unsettled truce between the granite monuments of democracy, including Arlington cemetery, and the super-size diet of empty calories ladled up by our commercial culture. It was all babble to me. I thought journalism, and young journalists especially, needed to play a stronger and braver role. I thought it was our job to bring the smelling salts, so to speak.

My father was an authority figure but he was not an authoritarian. He believed in a secular democracy; in the promise of civil rights for everybody and the importance of free speech. When he put out his flag on Memorial Day it was with a clear awareness that his uncles fought for this banner, and the imperfect democracy it stands for, against Hitler’s fascism.

Note to Justice Alito—this is the correct way to fly the flag…

My dad and I became pals late in his life. (He died of a heart attack on my birthday in late 2017). If he were alive today, I’d be flipping a cheeseburger for him on his grill near Lincoln Park this afternoon. It really wasn’t until he needed my help (he was struggling with his faculties near his end) that we got to know each other very, very well. He asked me to help finish the memoir he’d been working on. Our last months together were funny and moving and I found myself interviewing him, to better understand his recollection, to improve the chronology of his memoir, etc.

There are two of his memories sewn into one, from the same time period. On Pearl Harbor Day, 1941, (when he was nine years old) he remembers the smoke from smudge pots used to cloak the Panama Canal locks, to hide them from a feared attack by Japanese bombers. His father (my grandpa Charlie, who captained a canal drill boat) was at work miles away and dad remembers being afraid when he didn’t make it home that night. And then there was this memory, from his childhood in Gamboa, a town near the mid-point of the canal, deep in the rain forest.

—-Please support The Daily Rhubarb with a paid subscription—

“Sometime in 1944-45 our grade school principal and our teachers went to a bluff overlooking the canal, so we could see an aircraft carrier that was returning from the Pacific. The carrier was the U.S.S. Franklin. She was very badly damaged and listing to one side. The flight deck was full of scorched and twisted metal. As the carrier passed by, the principal told us it was an historic moment for us to remember. They still had not recovered all the bodies of the dead seamen buried in the twisted wreckage. The carrier was returning to New York to see if it could be repaired and sent back into battle. Hollywood would make a movie about it called The Fighting Lady.”

“Another day around this time I came home from school..and found my mother crying. I don’t remember ever seeing her so upset. I didn’t understand what was going on until she was able to tell me that my uncle Tom, her youngest brother, had been killed in action in France. What a shock that was to our whole family. I was old enough to remember Tom from the visits he made to our apartment in Staten Island before and after he went into the Army. This was the first time that I remember experiencing the grief and sadness of a great loss.”

Dad’s uncles, the Coyne brothers, photographed before seeing combat in Europe, from left to right, Thomas, Frank, and Joe.

Three of my grandmother’s brothers—-the Coyne brothers, from Scranton—served in the war in Europe. Dad was especially affected by his uncle Joe, who survived harrowing combat and returned with what, in those days, was called “shell shock.” Of course, we now call it “post-traumatic shock.”

Here’s a memory of Uncle Joe from his memoir:

“Joe told us not to get upset if he started hollering in his sleep during the night was he was still having nightmares and reliving some of his horrible moments during the war. After supper that evening we retired to the living room and, at that time, Joe gave me a big wad of religious medals and scapulas which he’d kept with him while he was in combat. He asked me to see if I could untangle them and I soon found that I could not. It was hard to even find an end to the tightly wound ball he had given me.”

My dad didn’t cry often, but he was often moved to tears talking about his uncles and their sacrifice. At the same time, their experience had given his life, and his service—both as an Army officer and a teacher and assistant principal—a grounding that was deeply inscribed in his identity and in how he approached his life as it unfolded.

He was an authority figure but he was not an authoritarian. He believed in a secular democracy; in the promise of civil rights for everybody and the importance of free speech. When he put out his flag on Memorial Day it was with a clear awareness that his uncles fought for this banner, and the imperfect democracy it stands for, against Hitler’s fascism.

It was for all these reasons he despised Donald Trump. He was on to Trump early on, dazed by how his popularity soared despite his racism, divisiveness and immorality. It was deeply confusing to him that Trump replaced Barack Obama in the White House. A clear subtext for that confusion and disillusionment was that Trump was (and is) the antithesis of what dad thought his uncles and the sailors who died so young aboard the U.S.S. Franklin had risked and given their lives to defend.

I’m grateful for the last year of his life. I was with him nearly every day and we managed to get to the bottom of everything a father and son would need to resolve. And we did it with love, and laughter, and deep respect. Yet, it’s also true he died confused about where his country was headed and confused about how that had come to pass. It’s not as though I had a good answer for him, or for myself, or for my children. Today I would tell him, if I could, that we’re working on it.

After he passed I brought the framed and mounted display of his uncles in uniform (above) to my apartment in Browne’s Addition and hung it in my living room. It was a small miracle it survived a fire in the building a year and a half ago. I put it in storage for my move, but retrieved it yesterday, so I could hang it behind me today, the way my dad would have flown his flag. It’s a way to thank them again, and bring them and their sacrifice forward, into the present.

—tjc